‘There’s other ways to help people’: The pre-meds who don’t go to med school

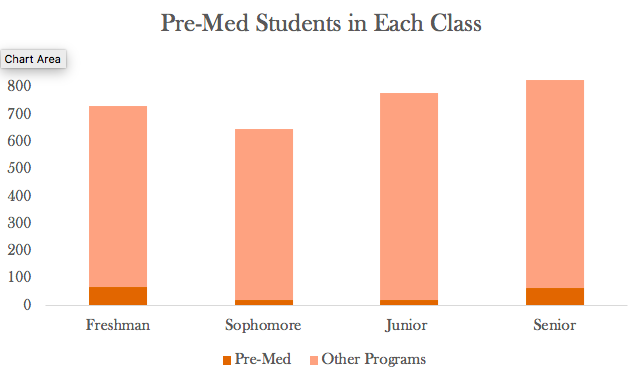

Data from Teri Crumb; Graphic by Sarah Gibes

About 10% of each incoming class is pre-med, but many fewer students graduate with the intention of attending medical school.

Calvin alumna Kathryn Hamilton knew her career path before she signed up to attend Calvin. After working in a Calvin lab during high school, she had her heart set on studying biochemistry while working through the coursework and extracurriculars necessary to enter medical school.

Today, however, Hamilton works at the intersection of science and business as a consultant, research associate and editor.

Hamilton’s path isn’t unusual. About 25% of each year’s incoming class is made up of pre-health students. Around 10% is pre-med, but a much smaller percentage actually matriculates at medical schools. Even though they enter Calvin with the intent of becoming physicians, many students discover their passions elsewhere.

Following others’ footsteps

According to chemistry professor and pre-medicine advisor Kumar Sinniah, students enter college with the intent to study medicine for many reasons. Often it’s simply the result of familiarity, given that the vast majority of kids interact with medical professions. Many Calvin students also have a desire to help others; they are attracted to medicine after seeing or receiving the care of physicians.

“That experience of seeing what physicians do draws them into the medical profession,” Sinniah said. “For these students, they see medicine as a noble profession.”

Zach Priebe, a senior biology major who will attend medical school next year, had his interest in medicine ignited during his sophomore year in high school, when major complications from a knee injury landed him in the hospital for a week and on IV antibiotics at home for a month and a half.

“During that time, all of the healthcare professionals treated me so well. I was more than just a patient,” Priebe said. From nurses who provided excellent care to the doctors who diagnosed and treated him, Priebe experienced the care and genuine servant attitude that shaped his own view of healthcare. One of his orthopedic surgeons was especially helpful.

“He was so empathetic. He got me interested in a career where I could treat people similarly to how he treated me,” Priebe said.

Other students have an interest in the biological sciences, and see medicine as the most logical career choice.

“I knew that I wanted to continue studying science and pre-med was sort of a logical next step as it seemed to pair nicely with this desire I had to make the world a better place,” Hamilton said.

Academic challenges

The path to an M.D. is long and arduous. The minimum academic prerequisites for medical school include organic chemistry and biochemistry, psychology and sociology, and upper-level biology. On top of the course load, students must also sit for the seven-and-a-half-hour MCAT, a comprehensive exam covering all of the pre-medical academic coursework, which itself requires hundreds of hours of studying. And that’s simply to gain acceptance to a medical program.

According to pre-health advisor Teri Crumb, some students just aren’t prepared for the academic challenges.

“Some people come in as pre-med, but then Chem 101 doesn’t go very well, and they know they will have to take 102 and organic and biochemistry,” Crumb said. “I sometimes tell them to see those early grades as a stop codon.”

Other students struggle with test anxiety. Given the test-driven nature of medicine – on top of normal course exams and MCATs, medical students take three nine-hour standardized licensing exams and multiple 10-hour board certification exams throughout their career – many students looking to medicine realize that the test-based career isn’t what they are planning for.

Even if students embrace the academic challenges, the cost and length of medical education – which takes a minimum of four years of medical school and three years, often more, of residency, and which can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars – turns some towards different career paths.

“I was looking at 8-10 years to achieve my desired specialization,” Hamilton said. “Combining that with the financial commitment, I would candidly say that my impatience got the better of me.”

Beyond the academic coursework and standardized exams, pre-medical students also must volunteer and work for hundreds of hours in clinical settings.

Katherine Koning, a senior biochemistry major, entered Calvin as a pre-med looking to earn a dual M.D./PhD degree. When she began volunteering and visiting hospice patients in their homes, however, she started to clarify her career vision.

“It was a good experience, but I realized this was not how I wanted to spend my career. The clinical hours were the thing that showed that,” Koning said.

“I definitely see when students realize what pre-med is like,” Crumb said. “They realize, ‘Okay, so I have to go to school for four years. Take this massive test. Then apply to this school where I have a max 38% chance of getting in and then four more years of school. $300,000 of debt. Work for three or four years in residency where I earn 80 cents an hour. And then I do a fellowship, and then I get to be a doctor.”

Uncovering other passions and professions

Like so many others, Stephanie Robinson, a senior strategic communications major, came to Calvin with the intention of going to medical school.

“I was interested in health and the body’s ability to heal,” Robinson said. Later, however, Robinson decided to switch her career to communications and get involved with conservative politics.

“This decision was the result of a lot of prayer and trusting God to establish my life path,” Robinson said.

Robinson’s academic path reflects a reality experienced by many pre-medical students: College provides students with new eyes and opens doors to opportunities that they hadn’t thought about before.

“When we enter college, we are very immature,” Sinniah said. “As we go through these four years, a significant maturity takes place. Suddenly we realize the world isn’t as simple as we thought it to be. Vocations are not what we thought them to be.”

Andre Kaptyn, a senior biology major, came to Calvin thinking he would be a physician. He liked science and wanted to serve in a developing country, and it seemed that medicine was the clearest way to combine those interests. Yet he soon realized that he didn’t enjoy working in a hospital.

“I love being in and around nature,” Kaptyn said, “I took into account that was the work environment I’d be happiest in.” He also realized through his biology coursework that there was an enormous amount of overlap between ecology and human health, and that ecology serves people and communities. He now wants to pursue a PhD in disease ecology, the study of the intersection between environmental and human health.

Service beyond medicine

Koning knew from the start that she wanted to pursue a career in research, but before college assumed the best way to serve people would be in a medical career.

“I wanted to do research that really affected people, and I thought an M.D.-PhD was the best way to do that,” Koning said. She started doing research during her freshman year and spoke sought career advice for medical research. It became clear that she didn’t need to get the medical degree or be a medical doctor to do what she cared about most.

“There’s a lot of careers that don’t involve working with patients, but involve working with other people. And just because you decide not to be a doctor doesn’t mean you don’t care about people,” Koning said.

Hamilton’s career followed a similar trajectory. During an interim trip to Nepal, she started to wonder if medicine was necessarily the best way to serve others. Contrasting the beauty of the Himalayas to the suffering that defined the lives of the enormously generous Nepali people she met, she realized that there was “tremendous potential for transformation at the intersection of things that are normally juxtaposed.”

With a new desire to serve by crossing boundaries, Hamilton went to business school. Today, she works in the emerging bioeconomy sector, where she can help deliver the discoveries made in the lab to people who need them.

“Once I saw the potential impact I could have on the bioeconomy working at the intersection of science and business, I never looked back,” Hamilton said. “I’ve found an opportunity to enjoy the study of science and the solutions it offers to business as a vehicle for change.”