Senior Michaela Blain reflects on four years of astronomy research

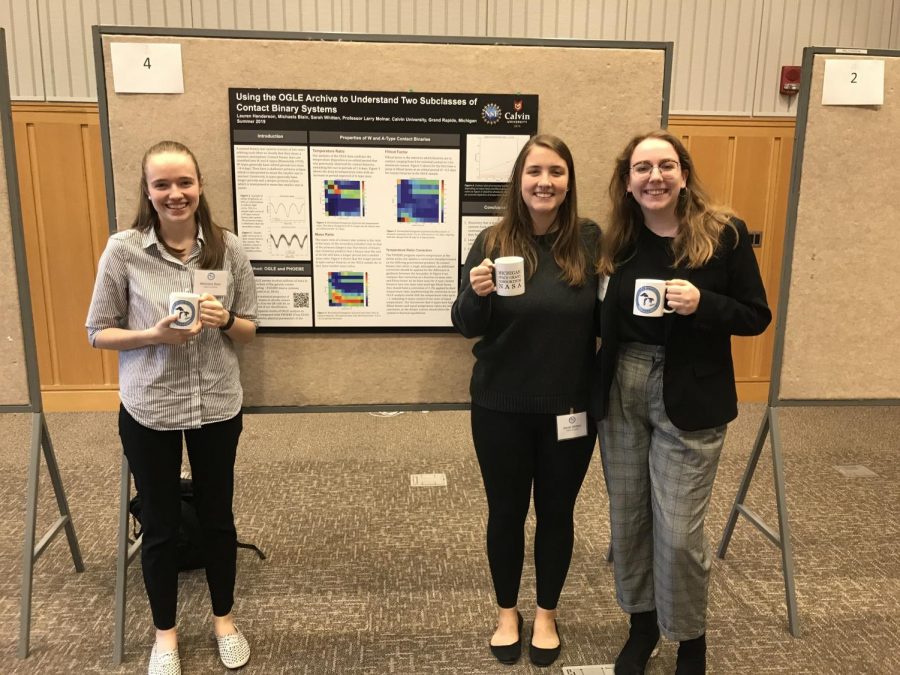

Photo courtesy of Michaela Blain

Senior Michaela Blain, left, presents her research on the formation of contact binary stars at the Michigan Space Grand Consortium in October 2019

Contact binary stars: like the name suggests, these extraterrestrial systems contain a pair of stars which share an atmosphere between them due to their extreme proximity. Although they’re ubiquitous throughout space, no one knows exactly how they come into existence. Physics and astronomy professor Larry Molnar first became interested in this area of study a decade ago due to the space-gazing work of his students using Calvin’s telescope.

Since then the research has been passed down through the years with many Calvin physics and astronomy majors contributing to it. One of them is current senior Michaela Blain. Since her freshman year at Calvin she has set her sights on helping to solve the mysteries of contact binary formation.

“I started by learning how to process and analyze data on the contact binaries we study,” Blain said. “Over the last couple years my work has shifted to focus primarily on making computer models of contact binaries as well as writing programs to fit a large catalog of contact stars to these models using Calvin’s supercomputer.”

This year Blain’s team consists of fellow senior Sarah Whitten and sophomore Lauren Henderson. Ultimately, the three girls desire to use their model of contact binary evolution to accurately decipher when and where certain contact binaries are forming and subsequently view their birth and development.

“It is still very preliminary,” Blain admitted. “We’ve only recently been able to start testing it against a large dataset of contact binaries.”

However, Blain sees a bright future for their model and considers it a “unique” and “exciting” contribution to the field of astronomy.

“There aren’t many astronomers studying contact binaries,” she said. “There are a handful of theoretical astronomers who have worked on describing and modeling specific stages or aspects of contact binary life, but no other group has gathered these pieces together into one holistic theory of evolution.”

The team uses a remotely controlled telescope in Rehoboth, N.M. that is identical to the one on Calvin’s campus found on the highest level of the Science Building. The student researchers occasionally take field trips to visit the remote telescope and talk about their research to professional scientists at conferences.

Recently they presented at the Michigan Space Grant Consortium in October and at the 235th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Honolulu, Hawaii in January. Last year Blain was honored with a Goldwater Scholarship for her significant contributions to the research.

“I am so thankful for the opportunity to be so heavily involved in this project during my time at Calvin,” Blain said.

Molnar praised how students like Blain greatly impact Calvin’s scientific research.

“A highlight of this work for me has been doing it together with students,” Molnar said. “It was student involvement that really spurred the work on in the first place.”