The regulations Calvin had and the students who broke them

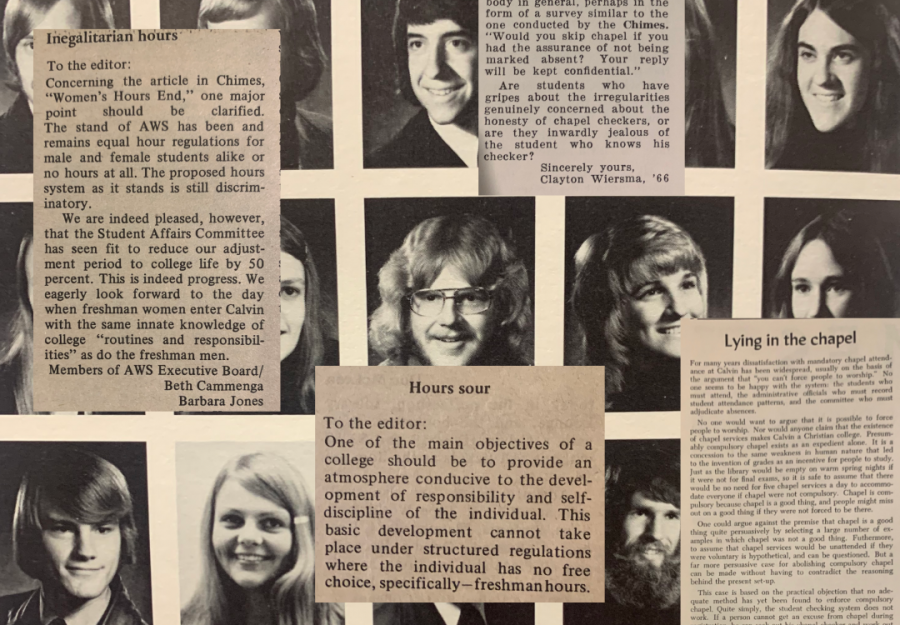

Vintage Chimes article excerpts on the rules Calvin once had.

Ever felt stifled by Calvin’s open house hours? Ever thought the code of conduct was too strict? Try being a Calvin student, especially a female Calvin student, prior to 1975. Here’s a tour of Calvin’s past rules and regulations and of the students who broke them.

The 1930s and 1940s

Bette Bosma attended Calvin from 1943 to 1947 and later returned to become a professor. At this time, Calvin was located in Franklin Street; the Knollcrest campus was still farmland. Following World War II, men who had been fighting in the Pacific and Atlantic theaters were returning home and going back to school. According to Bosma, the returners caused a headache for the administration.

Several men’s dormitories had been converted to women’s dorms during the war. Now that the men were back, the administration housed them at a nearby closed elementary school, and the veterans used to military life didn’t want to follow school rules. Attendance at daily chapel was required, and alcohol, dancing, playing cards and going to the movies were all forbidden.

Bosma, the second ever female editor of Chimes, lived at home, so she was not as affected by there being a curfew just for women and no open house hours. She still spent time in the study rooms in the dorm basements, where the women’s dean kept watch to make sure no men sneaked in. “We took turns having a guard out so when she came near we managed to move her away from the door,” she said.

Senior Kate Poortenga’s great grandmother Helen attended Calvin just prior to WWII. According to Poortenga, Helen saw a movie with three or four of her friends, some of whom were the daughters of faculty. The dean threatened to expel them unless they promised never to see movies ever again. Poortenga’s grandmother promised but soon realized that she wouldn’t be able to be true to that promise and returned to the dean, who quietly let them be readmitted.

The Late 60s and Early 70s

20 years later, the rules had lightened a bit. According to Michael Stob, who attended the Knollcrest campus from 1970-1974 and is a former Calvin math professor, and James Bratt, who attended both Franklin Street and Knollcrest and is a former history professor, there were open house hours on Wednesdays and Sundays, but doors had to be completely open, ensuring that the resident assistants could make sure that at least three feet were on the ground. Women still had curfews of 11 p.m. on weeknights and 12 p.m. on weekends. David Hoekema, who attended both Franklin Street and Knollcrest from 1968-1972 and is a former philosophy professor, lived off campus but dated a female student who lived in a Calvin dorm. “What I do remember is dropping her off at curfew time and seeing lots of couples trying to neck in the bushes without attracting attention,” he said.

Bratt echoed Hoekema. “It was quite the ‘make-out under the lights’ when you took your date back to her dorm at curfew,” Bratt said.

Additionally, alcohol consumption was allowed off campus. On Jan. 1, 1972, Michigan changed the drinking age from 21 to 18 to reflect the fact that the voting age was now 18. Bratt said, “As a senior I snuck lots of beer into the dorms for my younger friends, reserved the hard stuff for off-campus apartments.”

Stob said that the interim of 1972 was “pretty awful” when students became able to drink. Bars around campus tried to attract students to come in. Smoking was not only allowed on campus, it was ubiquitous. Professors would smoke pipes in class, and smoking inside residence halls was common for men but not allowed for women.

All drug use was forbidden, but according to Bratt, the administration did a poor job of catching offenders. He described how when the Grand Rapids Police Department conducted a drug raid in a men’s residence hall, the water pressure on campus plummeted because of how many male students were flushing illegal substances down the toilet. Bratt said, “Such a waste!”

Chapel attendance was still required but then only twice a week. Students had to schedule in with their classes when they would attend their mandated two services, and chapel checkers would make sure that they would actually attend. The policy ended in the year 1970, according to Hoekema, but students looking to avoid the requirement beforehand could bribe the chapel attendance checkers.

Dancing was not encouraged on campus but also not forbidden. Dances in the residence halls were called “movement with music” and Grand Valley University hosted a number of dances. Dance Guild was founded in 1971, and Hoekema recalled Calvin students laughing when Wheaton College decided in the early 1970s to stop disciplining students who had committed the crime of dancing.

The 1970s were a time of considerable expansion of women’s rights on campus. Female students began the decade having a curfew and being required to sign out if they left campus. In order to break curfew, female students would crawl through windows, prop open doors with sticks and have their friends sign in on their behalf. Women caught breaking curfew had to spend a weekend night studying in the dorm coffee kitchen.

According to a paper written by Rachel Koopmans, on April 1, 1971, a group of 250 female students protested the curfew by walking outside at 12:55. They marched around the campus while some male students catcalled and harassed the female marchers. After a half hour, the women returned to their dorms. Letters were sent to the women’s parents. Stob’s wife was one of the marchers, and her parents were very upset that their daughter had been breaking curfew.

According to Koopman, 96% of the female students’ parents approved of the curfew. A few years earlier, Calvin hosted a self-defense lecturer who advised that when under attack, a woman shouldn’t yell for help or fight but “go along with the attacked, even to the extent of rape.” “Gentleness” and “humility” were the best safeguards against rape. The curfew was seen as a protective measure for immature and weak women on campus.

From 1971 to 1975, female students continued to protest and both male and female students wrote editorials in Chimes, complaining about the curfew. Slowly, the curfew was abolished, starting with just seniors, until all grades were exempt.

Ben Aparicio • Mar 3, 2020 at 7:13 am

Well said and very intriguing, love to hear more about some of the odd rules that persisted into the 80’s and 90’s if there were ever time for it.