Gentrification panel speaks at GRPL

Panelists gathered at the Grand Rapids Public Library to discuss gentrification in GR. Photo by Morgan Anderson.

A panel discussion on Monday, Nov. 13, considered how gentrification is affecting the city of Grand Rapids. The event, called “Speak Up GR: Gentrification in Our City,” was held at the Grand Rapids Public Library and featured panelists such as Dr. Benjamin Ofori-Amoah, Darel Ross II, David Allen and Nancy L. Haynes.

Approximately 200 people showed up to attend the event, completely filling all the seats in the Ryerson Auditorium and leaving some to stand.

The discussion among panel members began by defining gentrification. Allen acknowledged that gentrification is a hot-button topic, especially in Grand Rapids, but that many people still do not know exactly what it means.

The panelists defined gentrification as involuntary displacement of a neighborhood’s inhabitants due to economic growth.

Allen described gentrification as people with the least amount of ownership becoming displaced from their neighborhood when more opportunity is created in the neighborhood from outside influences, like developers and outside businesses. The people originally from the neighborhood are unable to share in the increased opportunity.

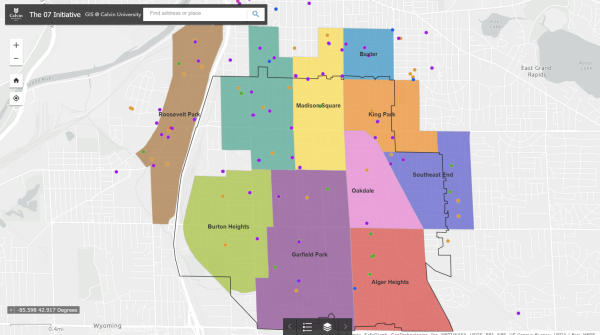

Some examples of gentrification in Grand Rapids are Eastown and the West Side where, in recent years, businesses have moved in and prices have gone up, encouraging original inhabitants to leave.

Then, panelists were asked to elaborate on the disconnect between neighborhoods and the opportunities found there. Panelists acknowledged that there are a lot of revitalized areas in Grand Rapids, which is a good thing, but that simply revitalizing the area is not enough.

“We need to elevate our game when revitalizing deals with people where we’re helping our social fabric,” said Ross.

Panelists agreed that true revitalization isn’t merely on the surface with newly built houses and neighborhoods’ visual appeal, but it’s built into the people of the community. Gentrification is one possible result of revitalization, but it isn’t the only option.

Next, the topic turned to questioning why gentrification is a hot-button topic.

Panelists argued that gentrification is a hot-button topic due to the displacement that gentrification causes. As cost of living goes up, there are fewer and fewer houses to live in. This is exacerbated by newcomers to the city and the student population, and has caused lots of low-income minorities to move to the outer suburbs of Grand Rapids.

The panelists argued that the only reason that people are starting to care about the housing situation in Grand Rapids is that there’s a house affordability problem added on the preexisting affordable housing problem. House affordability describes a situation where it is difficult for middle class families to afford housing. Affordable housing describes “subsidized housing,” where housing is offered at a percentage lower (usually 30 lower) than the median income of the (usually low-income) area. Panelist Allen shared that as of November, there are only 242 available single-family homes in Grand Rapids, with price tags for a single family home that range from $4,000 to $1 million.

Another problem to this is the added complication of vacant houses, about 800 in Grand Rapids alone. These vacant houses are from the 2008 economic crisis, in which banks repossessed homes. However, there are now government regulations for properties that do not allow them to be sold unless they fit certain conditions. It’s easier for banks to simply sit on a property than to fix it up in order to sell it.

Another problem is investment companies in Grand Rapids that own lots of properties are continuing to increase rent in such a way that is not proportional to inflation.

The discussion then turned to what goals the city should have concerning affordable housing. Panelists expressed their desire for the City of Grand Rapids to start defining a healthy community. Ross in particular supports establishing regulations concerning: building vs. density structure, renter vs. owner density, affordability requirements, etc.

Furthermore, panelists elaborated on how developers and communities can work together. Ross suggested that unity between developers and communities can only happen when both parties are “brutally honest” in order to work together. The City of Grand Rapids and other municipalities’ job can then be to help establish middle ground between the developers and communities.

“We still live an environment where everything is pro-developer,” said Ross. “We have to get to that communities should be unapologetically is pro-community. Right now communities are the strongest voice for communities.”

The panel also discussed steps people can take to get engaged with the Grand Rapids city government concerning issues of gentrification. Some of the easiest actions a resident can take is to call their commissioner and be concrete about what they want in a coherently articulated way.

“You have to stay present, rested, diligent, you have to stay a part of the process,” said Ross. “Development is a mathematical game and right now we’re playing on [developers’] heartstrings to not make more money.”

One of the 200 attendees was Calvin graduate Jacobus Verrips ‘17 and Tonisha Begay ‘17. Verrips feels that this is an important topic for students to consider.

“Young people should care because it directly affects them,” said Verrips, “Housing is a difficult thing in general, but those who wish to stay in GR especially should begin to look at this issue more seriously and be more intentional about where they move as to not displace others.”

Begay thought the slow cadence of progress particularly interesting:

“I’m realizing more and more that issues like this take time to untangle and there’s nuance to be found, but it takes time to figure out what everybody’s interests are,” said Begay. “One thing I took away from the event is that issues like the housing crisis in Grand Rapids will not get fixed overnight. It takes everybody getting on the same page for change to happen, but change at the local level is painfully slow.”

The panel ended with a final encouragement to listeners:

“Just stay engaged,” said Ross. “Don’t assume anyone wants more for your neighborhood than you. Look at the policies and structures that are perpetuating our neighborhoods.”

Ofori-Amoah agreed, adding “You need to get involved. You are the only people who can change [your neighborhood].”

From 2001 to 2006, Ofori-Amoah served as the chair of the department of geography and geology at the UWSP. Since 2006, Ofori-Amoah has served as the chair of Western Michigan University’s department of geography.

Ross was the LINC UP’s board of directors treasurer for nine years and is now the co-executive director. Ross has helped raise “$67 million in funding for community improvement efforts resulting in over 300 families increasing their assets, training over 600 residents, improving over 750 homes, and creating 120 full-time jobs,” according to LINC UP.

Allen currently serves the City of Grand Rapids as a Third Ward commissioner. Allen is also the executive director of the Kent County Land Bank Authority (KCLBA). Allen’s speciality is in urban community revitalization, and he has founded successful development organizations for communities which include Oakdale Neighbors, City Vision and Lighthouse Communities (now LINC UP).

Haynes serves as the executive director of the Fair Housing Center of West Michigan (FHCWM). Haynes also serves as the secretary for the National Fair Housing Allegiance board of directors and “has provided independent consultative and training services to a broad range of government, community-based, and political/public interest organizations as well as the private sector,” according to the GRPL. Haynes was a past president of the Women Lawyers Association of Michigan—Western Region.