Today, Republican presidential hopeful Nikki Haley will be the latest in a long line of political candidates to make a stop in Grand Rapids in recent years. As Haley hopes to thwart former President Donald Trump for the nomination, she’ll be hosting a rally downtown at the Amway Grand Plaza.

Wherever Haley’s motorcade route takes her today, it will be within a stone’s throw of Calvin University, an institution that finds itself caught in the middle of nationwide political turmoil.

A trip through the university’s institutional archives suggests that it has always been thus. Perhaps it’s swingy West Michigan, a region at play in the blue state of Michigan. Perhaps it is the peculiar makeup of Calvin’s student body and its approach to higher education. Either way, a history of engagement with political controversy was, and continues to be, a significant part of Calvin’s institutional story.

As the university once more looks towards a polarizing and contentious presidential election in November, and synod in June, past moments of controversy provide context for understanding the Calvin community’s political climate today.

This article is the first in a series exploring how Calvin has navigated civil discourse over the years, as well as how it attempts to navigate divisive issues in the months and years to come.

The current Calvin context

Regardless of who wins the election, American trust in the government is at a significant low. Data compiled by Pew in late 2017 indicates a growing amount of political polarization, as Americans are “less likely to have a mix of conservative and liberal views” as compared to 1994 and 2004, and are more likely to be ideologically consistent.

As America’s political divide widens, documents codifying policies about freedom of expression — written by faculty and administrators and approved by the Calvin Board of Trustees — encourage people to “enter into brave spaces with confidence that doing so will strengthen individual convictions by engaging differing viewpoints in communities that welcome diverse voices and perspectives into the conversation.”

A vice president comes to campus

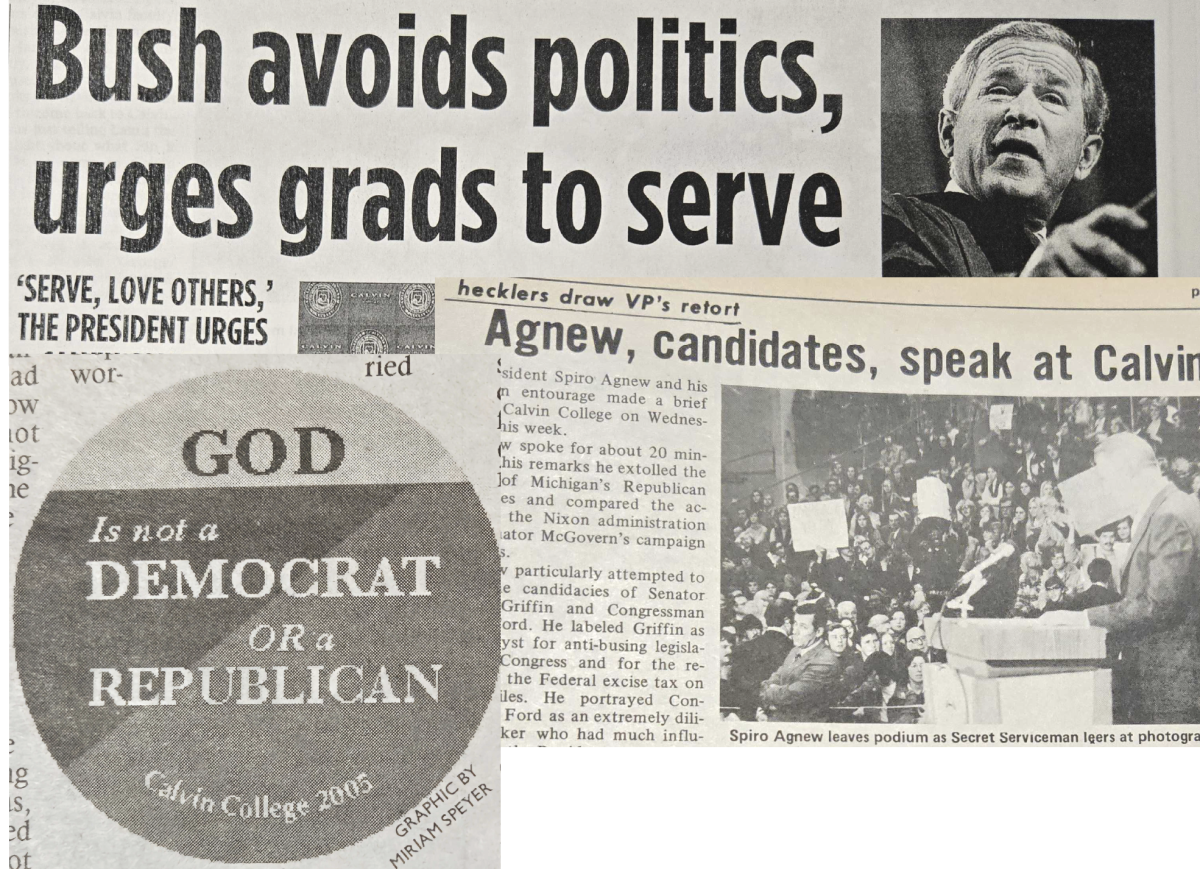

In October of 1972, Nixon’s Vice President Spiro Agnew came to Calvin to campaign for Republican candidates Robert Griffin and Gerald Ford. Between 5,000 to 6,000 people attended the event, and national media picked up the story. The rally was intended to be educational and was sponsored, nominally, by Student Senate, according to letters from then President William Spoelhof. However, the Kent County Republican Party took over most of the arrangements, Spoelhof wrote.

Former Provost Joel Carpenter, who was a student at the time, remembered the Republican party bussing in large numbers of high schoolers to sit in the stands behind Agnew where the TV cameras would point. These high schoolers were to cheer for Agnew, because “We need some footage of the Vice-president with young people in the background for his ‘76 campaign,” an advance-man with the campaign told a Chimes reporter at the time.

However, Agnew was not met with fervent support. “In his 20-minute speech, Agnew was interrupted several times by rebuttals from the crowd. Shouts and chants of ‘stop the war’ and ‘Agnew you butcher’ were consistently voiced,” according to previous Chimes reporting.

Students and alumni also wrote letters to the editor criticizing Agnew’s event, particularly its politicization. “We invited him essentially to explain his and President Nixon’s views in this presidential election. Instead of that, Calvin hosted a calculated, emotion-packed political rally,” Ronald Voogt, a student who graduated in 1973 wrote in a letter published in Chimes.

In response to controversy around the event, Spoelhof wrote that much of the disrespectful protestation was from non-Calvin groups and the few disruptive students were being dealt with. In conclusion to one of his letters, Spoelhof wrote, “I think my chief error was in thinking that we could have a sober, sane discussion of the political issues.”

A presidential commencement

Spoelhof’s reflection on the aftermath of the situation to his constituents stands in contrast to former Calvin president Gaylen Byker’s response to similar controversy faced when President George W. Bush spoke at Calvin’s commencement ceremony in 2005.

Kyle Heys, now Calvin’s Director of Student Success and TRIO, was a student at Calvin from 2001 to 2005. Heys remembers it as an “exciting time” to be on campus, where professors across several departments organized teach-ins about the war in the Middle East and ran ads in the Grand Rapids Press protesting the college’s decision to host Bush. “[Bush] seemed to know the people that were here, and I think to see him pay that attention to this kind of place was interesting,” Heys told Chimes.

When the news of Bush’s commencement speech broke, a number of faculty took out a half-page ad in the Grand Rapids Press to make known their disagreement with Bush and his policy. “‘It was our attempt to make clear that our Christian convictions lead us in different ways on policy matters than the president’s Christian convictions have led him,’ George N. Monsma Jr., an economics professor who signed one of the ads, said before the graduation ceremony. ‘We plan to be gracious hosts, but this is part of a long Calvinist tradition of speaking truth to power.’” Monsma’s remarks were found in reporting done in the Washington Post.

Before and after the event, Byker and other members of Calvin’s administration received high volumes of emails and letters from alumni, donors and other members of the CRC. One folder of Byker’s correspondence contained letters of support for Byker’s decision to host Bush, as well as to allow faculty to dissent. Many writers praised the diversity of viewpoints and the expression of academic freedom the university allowed.

Around eight folders were full of letters people wrote to note the honor of Bush’s involvement as well as to condemn the liberalism and perceived disrespect shown to the president by students and faculty. Bush spoke at only two commencements in 2005: the U.S. Naval Academy and Calvin.

“Probably three to one of the calls and posts that Pres. Byker and I received were from angry constituents who were appalled at the faculty’s efforts to send a message to President Bush,” Carpenter, Calvin’s provost at the time, told Chimes in an email.

There are six folders of varying size in the collection containing writing from people who complained to the administration about Bush appearing on campus at all, largely due to concerns about appearing partisan or associating Christianity with conservatism. Alumni cited their own transformational education at Calvin as the reason they opposed Bush and his policies.

In response to similar concerns among students, John Zwier, a senior at Calvin in 2005, worked with the College Republicans, the Social Justice Coalition and Calvin College’s administration to offer an “opportunity to express their hope that President George W. Bush does not politicize religion during the Commencement ceremony of 2005,” by the creation, distribution and display of buttons that said “God is not a Democrat or Republican,” according to a Chimes article Zwier wrote about the plan.

“This visual statement is not divisive but encourages the type of intellectual debate for which Calvin College should be known: open dialogue about Christianity’s role in the world,” Zwier wrote in the May 6 Chimes article.

Given the amount of feedback Calvin received, Byker released a public reflection on the 2005 commencement in which he explained and offered a rationale for the decisions the university made.

“That kind of event and dialogue is exactly what an engaged Christian college should be doing — challenging one another to think carefully and Biblically about important issues,” Byker wrote. “And it is clear at Calvin College that well-meaning believers who agree on the essentials of the faith and that affirm the mission of our institution can disagree, not only on matters of politics and public policy, but in all academic areas.”

According to Heys, Bush’s visit brought the national political conversation to Calvin, and “it felt like people were being thoughtful about what it meant to engage the political process.”

Contemporary conversations

Similarly, Betsy DeVos’s nomination to Trump’s cabinet as the secretary of education generated political discussion on campus. A number of alumni signed a letter protesting her appointment, and in reaction, many more voiced their support, according to previous Chimes reporting.

DeVos came to visit Calvin in 2022 after her term as secretary, as a stop on her book tour. Because of the visit’s timing around mid-term elections, Calvin refrained from publicizing the event until after the election. “When we talked as leaders of this we were like, ‘we don’t want to look like this is political at all, because it’s not,’” Brian Bolt, dean of education told Chimes in previous reporting on DeVos’s visit. Comments on that Chimes story include criticisms of Calvin’s continued association with DeVos and condemn the institution’s provision of a seemingly “uncritical” platform.

Students tabled outside the event to express their disagreement with DeVos’s school choice policy that could harm LGBTQ+ students. John Walcott, professor of education, wrote an opinion arguing for more conversation about DeVos’s visit, not criticizing the decision to host a distinguished alumnus, but clarifying how her policy is harmful and that sponsorship from the school of education did not denote endorsement.

In the conclusion to the opinion he published in Chimes, Walcott wrote, “And I remain hopeful that we, as a community, will embrace the opportunity to not only offer diverse perspectives, but also engage deeply in important conversations of what it means to think deeply, act justly and live wholeheartedly as Christ’s agents of renewal in the world.”

Options for engagement

Ways of framing and engaging in controversy that enable disagreement without division will be useful as Calvin grapples with controversy within the CRC denomination. Synod 2022 established a contested doctrine of confessional status surrounding human gender and sexuality. The issue has caused controversy in the CRC as early as the 1970s, but has erupted in recent years.

Loren Haarsma, professor of physics, has presented at the CRC Synod in past years on topics including human origins. The subject of human origins has historically been divisive in CRC circles, although in the past few years, the theological conversation has shifted somewhat. Haarsma described his way of framing difficult conversations.

“What we like to do is often, on these controversial issues, start and end by talking about what we all agree about, and then in the middle, talk about what are the pros and cons of various options Christians are considering. And that approach is generally well received,” Haarsma told Chimes.

The Freedom of Expression document written by a committee and approved by the Board of Trustees in 2019 outlines a similar approach. This document (and an update to the “Policy for Hosting Political Candidates or Issue Advocates,”) moved to formalize some of the policies already in place around civil discourse, freedom of expression and cultivating a “brave” yet healthy space for students according to previous Chimes reporting.

Some students have reported disappointment with the university’s middle-ground stance, particularly surrounding sexuality, while others report feeling as if more conservative positions are shut down by faculty. Regardless, students across the political spectrum see a focus on learning, relationship and respect as keys to engaging well across differences, according to previous Chimes reporting.

Going into Synod 2024, Haarsma hopes discussion stays “Christ-focused.” “When there’s a controversy, it can be very tempting to try to draw boundaries,” he said, or alternately, ignore the issues completely. “But there’s a third approach, which I think really works well. It’s to try to be Christ-focused. To say, how can we deal with this controversial topic in a way that makes us more Christ-like?” Haarsma said.

Consistent refrains

Sara VanderHaagen, professor of communication at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, has done scholarly work on the 2005 Bush commencement address at Calvin. In her work, VanderHaagen emphasizes the ability of institutions like Calvin to tap into a shared “public vocabulary” when approaching controversy. Language such as living as agents of “renewal” is one such shared starting point.

Calvin has faced criticism from both sides of the political aisle for some time, as evidenced by each of the above situations. And as far back as 2005, the administration’s hope was to position Calvin as a place for “intense dialogue about the world and society” and a place where people can disagree and yet still converse in “convicted civility” as agents of renewal, according to letters from Byker addressed to alumni, donors and members of the Christian Reformed Church (CRC) concerned about Bush’s commencement address.

Today, Calvin remains committed to being a place to hold hard conversations. “I think that Calvin has an opportunity to distinguish itself by resourcing, structuring and foregrounding opportunities for discussion, dialogue and conversation across difference,” Provost Noah Toly told Chimes. “I don’t think the uniqueness is going to be in having them [conversations across difference]. I think the uniqueness is going to be in demonstrating our concrete commitments to them.”

James van der Klok • Feb 27, 2024 at 9:27 am

It’s interesting that 100% of the outside speakers noted are all conservative Republicans. If, as Professor John Walcott noted, the intent of Calvin is to “embrace the opportunity to not only offer diverse perspectives, but also engage deeply in important conversations of what it means to think deeply, act justly and live wholeheartedly as Christ’s agents of renewal in the world,” why does it appear that only more conservative perspectives are being given a platform?

Duane Kelderman • Feb 26, 2024 at 10:25 am

I was at the Agnew event and remember the hecklers well. The heckling went way beyond voicing opposition to Agnew and his party and was downright rude and inhospitable. Unable to moved on with his speech because of the heckling, Agnew paused for a long time, looked toward the back of the room where the hecklers were, and when it finally quieted down, wagged his head and said, “Yeah, at this time of the year (October), even the screens can’t keep ’em out.” The crowd roared in laughter and approval. With one quip, Agnew won over the crowd and silenced the hecklers. I often wonder how many times he used that line.