Calvin’s progress on carbon neutrality, sustainability murky during pandemic

According to the most recent 2019 STARS Report, Calvin has made progress on carbon neutrality. It’s unclear if efforts have continued.

Five years after committing to carbon neutrality, Calvin still lacks a centralized movement to move towards its goal, and it’s unclear whether the university has met its carbon reduction commitments.

According to the climate commitment, which University President Michael Le Roy signed in December 2017, the university committed to “complete an annual evaluation of progress.” Yet no updated data on Calvin’s carbon footprint have been released since the COVID-19 pandemic started. The most recent carbon information was submitted in February 2020.

Calculating Calvin’s carbon footprint

Calculating an institution’s carbon footprint is complicated. There are two main elements, one summing the total equivalents of carbon outputs and one counting the total equivalents of carbon removed from the atmosphere and added to plants or soil. Carbon outputs include everything from the energy used to heat up water to the carbon smoke dumped into the atmosphere at the coal-powered plants that provide Calvin’s energy. Carbon removal occurs when plants pull carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere — for example, when the trees in the nature preserve grow — as well as through actions that return carbon to the soil, such as through the dining hall’s composting initiatives.

In the past, student interns have collected data about Calvin’s energy usage. Students’ data was verified by a group of faculty members and Russell Bray, the director of the facilities department. After this, the information was submitted to STARS, which collects information from multiple institutions and rates their performance, based on the report available on the STARS website.

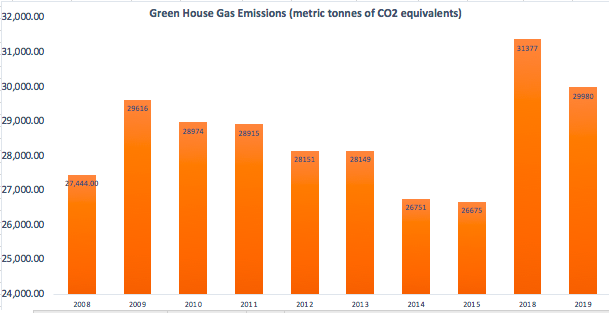

For data collected in 2019, Calvin had a STARS greenhouse gas emissions rating of 1.89/8.0, with 0 as the worst rating.

There is no more recent data available. For the past two years, Calvin has not released data about its greenhouse gas emissions, according to Becky Haney, economics professor and member of the Energy and Environmental Sustainability Council.

“The pandemic actually prevented us from updating the report this year,” Haney said. “The change in emphasis of what facilities had to do, we just didn’t have the bandwidth to get further traction on renewable projects.”

The decision to outsource labor in the facilities department to contractors, which resulted in many facilities employees leaving Calvin, has also hampered the project, according to Haney. There are currently no student interns collecting data about Calvin’s energy production.

Bray did not respond to requests from Chimes staff for comments.

Downward trend unclear

According to engineering professor Matthew Heun, who is member of the EESC and leads classes evaluating carbon emissions for Habitat for Humanity, the general trend of Calvin’s carbon emissions is downwards. Calvin’s carbon footprint has generally decreased for each year for which data was collected in 2019 and before. It’s not clear, however, if the downward trend is solely the result of better efficiency, given that Calvin’s student population has also been in decline.

“It’s probably better efficiency and having fewer students that’s driving it down,” Heun said.

It’s also unclear if the downward trend has continued since the 2019 report. Changes to Calvin’s facilities in the past two years will likely have significant impacts on Calvin’s carbon footprint.

Since 2019, Calvin has reduced its facilities and halted programs that contributed to carbon sequestration. Sequestration occurs whenever carbon is removed from the atmosphere. Plants do this during photosynthesis. It also occurs when carbon is put back into the ground, such as during composting and decomposition. At Calvin, trees and composting are the most visible avenues through which carbon sequestration occurs.

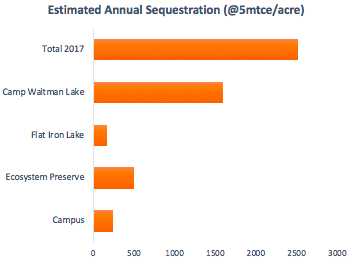

Calvin sold Waltman Lake, a heavily forested property which was a significant course of carbon sequestration, in 2019. There is no publicly available report on Calvin’s emissions and sequestration without the Waltman Lake property, according to Heun and Haney.

“[Waltman Lake] was a huge amount of our ability to offset carbon emissions,” Haney said. “After selling that, we’re going to have to make up for those acres a bit.”

Composting, another important carbon sequestration source, has also been put on hold during the pandemic. Due to the lack of reporting, it’s unclear how much of an impact this has had on Calvin’s net footprint.

In addition, the university is in the process of constructing a new business building. Although the building has been built with sustainability in mind, Heun noted that it will still increase Calvin’s net building energy consumption.

Building contributions

Buildings are a significant contributor to Calvin’s carbon emission. According to the STARS report, Calvin has a building efficiency score of 0/3.0 and a clean and renewable energy score of 0/4.0.

STARS determines building efficiency scores based on how many square feet of building space meet “published green building codes, policies, and/or rating systems.” The clean and renewable energy scores are determined by evaluating the amount of energy that the institution obtains from “certified/verified clean and renewable” sources.

Based on data in the STARS report, Calvin has 0 square feet of building space that meets published sustainability codes. Only 0.02 percent of Calvin’s energy usage comes from clean and renewable energy sources.

Many of Calvin’s dorms and academic buildings were built before sustainability concerns informed building construction. Yet Heun noted that, despite the outdated construction, there are still multiple options for improving building energy efficiency.

One option is to better insulate buildings. Another is to decrease the amount of energy used by appliances in the buildings, such as lights and water boilers. One of the most effective methods is to decrease the amount of per capita building space.

“It seems like Calvin is going in the opposite direction on building space,” Heun said, referring to the construction of the new business building and plans to construct a new Commons Union.

Student groups at Calvin have worked to improve the institution’s energy use efficiency. Over the past 10 years, the Calvin Energy Recovery Fund, a group of engineering students who plan and implement sustainability initiatives, has replaced almost all of the lights on campus with LEDs.

According to Heun, there is still significant space for progress. Calvin’s water-heating systems, for example, are old and inefficient. Replacing them would significantly decrease energy consumption.

Energy production

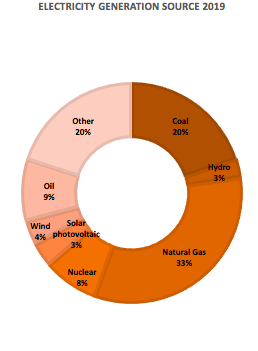

Besides reducing consumption, Calvin could also invest in its own clean and renewable energy production. The university currently receives the vast majority of its energy from the West Michigan grid, which is produced and regulated by Consumers Energy, according to Heun. CE currently relies on coal for energy production, which emits significant amounts of carbon dioxide.

In addition, CE-produced energy also has to be transported from the production site to the university, which takes additional energy. Investing in on-site production of cleaner and carbon-neutral energy would significantly decrease Calvin’s total carbon emissions.

“We could buy our own machine to make energy from natural gas, which is cleaner than the coal we get from the grid,” Heun said.

Heun also sees the significant amount of unused roofs on campus as prime space for solar panels. “We could plaster buildings with solar panels,” Heun said. “That would mean we could use a carbon-free source, which is especially good for the summer, when energy demand is highest due to air conditioning.”

Sustainability in curriculum

Although Calvin has struggled to reduce its carbon footprint, the institution has successfully implemented sustainability education initiatives on campus.

“There’s a lot of rollout of sustainability across the curriculum. There’s so much it’s hard to unpack,” Haney said. Calvin has several successful curricular sustainability initiatives going on. One of the most successful is Kill-A-Watt, a program in which dorms compete to decrease their carbon footprints. Engineering students can complete a sustainability concentration. The university’s new core also requires students to complete a course with the sustainability tag.

In addition, the university plans to launch a sustainability cohort to enhance student engagement with sustainability issues, Haney said.

Beyond curricular requirements, there are numerous student organizations on campus that engage with sustainability-related issues. According to Isaac Spackman, student representative on the EESC, students can work with the nature preserve, Plaster Creek Stewards, Service Learning Center or the Clean Water Institute, as well as in dorm leadership and CERF and STARS student intern positions.

Despite the multitude of available options, the decentralized nature of Calvin’s sustainability initiatives make it difficult for individual organizations to have a significant impact on the university’s institutional-level decision making.

“While Calvin has many programs involved in sustainability, for the most part these programs are not centralized in a way that makes them easy to learn about or become involved in,” Spackman said in an email to Chimes. “Calvin’s carbon neutrality efforts are even harder for students to access, perhaps in part due to lack of action on this issue from administration.”

President LeRoy did not respond to requests from Chimes staff for comments about administrative efforts towards carbon neutrality.

Even though sustainability has been a topic of discussion at Calvin for over half a century, and individuals have been taking action for at least the past 25 years, it’s always been bottom-up, grassroots-style organizing, according to Heun.

“We lack a centralizing force on sustainability,” Heun said. “We’ve never had any sort of top-down on sustainability on our campus. I think the most important thing Calvin could do would be to hire someone with the Calvin carbon story as their job title.”

In 2017, the sustainability taskforce noted that Calvin had a “clear need for a Director of Sustainability.” Assigning an individual the distinct responsibility to coordinate sustainability efforts across campus would improve coordination and increase the transparency and accountability of carbon neutrality efforts. The Sustainability Taskforce Report recommended three options, either repurposing the EESC to be a member of the president’s council, create a Director of Sustainability position or create an Office of Sustainability, with a Director of Sustainability offering additional support.

As of 2021, none of the recommendations have been followed.

The report similarly suggested that investment in sustainability would positively impact Calvin’s enrollment. According to a 2016 Princeton Review survery, 61% of prospective students consider a college’s sustainability commitments in their college decisions. To meet its recruiting goals, Calvin should invest more in its sustainability.

Looking into the future, Mary Tuuk Kuras, the chair of the Presidential Search Committee, stated that the university’s commitment to sustainability, in the context of Calvin’s “anticipated direction,” is a factor in the selection of Calvin’s next president.

“The anticipated direction includes sustainability efforts and strategies currently in place at Calvin,” Tuuk Kuras said in an email to Chimes. “The current strategic plan embraces and enacts sustainability as a core value.”

According to Heun, Calvin has so far failed to be a leader in sustainability. “I think Calvin has the opportunity to be a leader in this area,” Heun said. “But we’re not harnessing that potential.”