Center for Counseling and Wellness makes changes to therapy tactics, students share their experiences

Dr. Irene Kraegel of the Center for Counseling and Wellness at Calvin College wants to expand the social definition of therapy beyond individual sessions. However, this doesn’t seem to be what many students want, with some commenting that certain therapy options feel like cheap alternatives for the care they really want — individual sessions.

When most students come to the center, what they expect is an individual session with one of the center’s counselors (perhaps while lying on a chaise lounge). However, the reality is different from this popular idea of therapy, and Kraegel would argue that this reality is better.

When a student walks into the Center for Counseling and Wellness, they may notice the soothing piano music playing over hidden speakers, the complimentary Keurig coffee and the coloring books with gel pens on the coffee table. Also on a first visit, a student fills out a screening form that asks questions about what symptoms they are experiencing, the severity of these symptoms and how these symptoms are affecting other areas of their life.

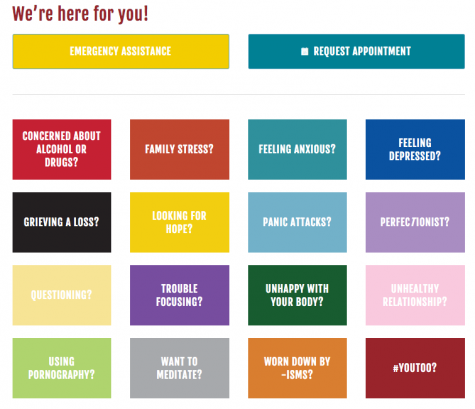

After a preliminary 15 minute discussion with a counselor, an individualized plan of care is made for the student based on the center’s Stepped Care Model. Far from just individual therapy, this model offers a variety of options with various levels of involvement, such as peer listening, Therapy Assisted Online (TAO) modules, workshops on anxiety and depression, group therapy sessions and finally individual therapy.

Kraegel reports that the center adopted this model in January 2017 to help with wait times. The center was seeing an influx of new students, probably due to reduction in stigma, Kraegel thinks, but this meant that students had to be put on a waitlist before they could meet with a counselor. According to a 2018 report from the Center for Collegiate Mental Health, colleges across the United States are experiencing a similar increase in need. This often leads to counselors “absorbing” new students into their existing caseloads, meaning that follow-up appointments can be weeks apart, or leading to counselors taking on only a certain number of cases to maintain weekly appointments.

However, after the center implemented the stepped model of care, Calvin students could get in the same day for at least a preliminary screening. Because of this, Kraegel notes that Calvin is doing much better than other colleges in this regard. Additionally, Kraegel likes the fact that the stepped care model challenges the current narrow definition of therapy. She said, “people are a little less likely to think of the many different ways to receive mental health support and treatment, beyond just talking to an individual counselor.”

However, not all aspects of this model of care seem to be for the better. Students Abigail, Megan, Hannah and Marissa, whose names have been changed to respect anonymity, commented on the current therapy options..

Megan, Hannah and Marissa do acknowledge the difficulty of understaffing, but they think that this model of care is not necessarily the best solution. Hannah mentioned that the group therapy sessions in particular seem to be “a band-aid issue for the lack of counselors,” and that she doesn’t like feeling that “the big groups are an idea to make up for understaffing.”

The center offers two main workshops: “Anxiety Toolbox” and “Getting Unstuck” for depression. The counselors from the center lead the workshops, often working through educational materials. Kraegel explains that the workshops are different from group therapy in that “it’s for people who want to come and learn skills around depression and anxiety.”

She continues, “They’re not looking for a lot of in-depth interaction, or vulnerability, or connection in that way.”

Megan disagrees. She said, “I don’t need super intensive care, but I want a space to process my feelings that’s not with other people.” She continues, “I think all I really wanted was to talk about my feelings in that depression, and not talk about, ‘this is depression.’” She said that although the group verbal processing or educational aspects might be helpful for others, it wasn’t what she needed. Megan didn’t attend another session after that one.

Marissa feels similarly. She attended three weeks of the “Getting Unstuck” workshop on recommendation by a counselor, but said it “wasn’t well-suited for me, a person who’s aware of my own depression and depressive tendencies. It was more suited for people sunk into their depression and who don’t have a good grasp of how to get out.”

Because of this failed experience, Marissa explained that she was worried that other people were similarly “going through things that might not work to get to the real stuff they need.” Hannah also commented on the fact that group therapy might not be the best fit for everyone, and that it wasn’t necessarily a good idea to recommend it to everyone.

When Hannah first came to the center, a group therapy for survivors of sexual assault was recommended to her after her screening, but she insisted on individual therapy. She said that she did individual therapy for two years before considering group therapy. Hannah notes that part of not going to group therapy was due to conflicts with extracurriculars, and partly due to the difficulty of opening up to one’s peers.

She said, “I think it takes a lot for someone to personally say, I have been sexually assaulted. And that took a lot for me to get to there with myself. And then they recommend to go and talk about it with a group of people. That is hard! Especially when you’ve just come to terms with it by yourself.”

Another stumbling block to getting care is the paralyzing effect that mental illness can have. Marissa said, “It takes a lot of effort to reach a point where you know you have a problem and then to get help.” She also said she feels the stepped model of care “discourages people from seeking one-on-one help they really need, because they have to jump through hoops or show they really need the help, that their issue is bad. It’s time-consuming to go through these just to get a one-on-one.”

Again, stigma plays a role. Hannah said, “I didn’t go for weeks because there’s a little bit of a stigma around getting treatment. I think the people there should take more initiative with the students who walk in, because it already took a lot of effort to walk in.”

Kraegel does acknowledge the effect stigma can have, but she emphasizes the strengths that students bring to the process of therapy. “Nobody gets this far without having some strengths along the way and some resilience.”

And this resilience can be built in community. One aspect of group therapy that Kraegel said is especially effective is that of human connection.

“We find that those groups and workshops seem to be addressing a need in terms of people talking to each other about what they’re experiencing.” She continues, “Or even if they’re not talking about it, just being in a room with people where you know we’re all here because we’re struggling… that in itself can be validating or affirming.” Abigail agrees. She mentioned that group therapy was helpful in making her see that she was not alone.

Her first year at Calvin, Abigail attended the female Step One group, which helps students with pornography addictions. It was intimidating at first, she said, since she had joined halfway through the semester, the other girls were juniors and knew one another already, and she didn’t talk much her few first meetings. But then one day Abigail was talking through something difficult and made a joke about it, and all the girls laughed. “I think that was just a breakthrough of, like, wow, these guys understand to the point where we can laugh about it.”

Community seems to be key to both ending stigma and increasing quality of care. Hannah and Megan brought up the idea of introducing first year students to the center and its various resources, perhaps as part of Quest or First-Year Seminar, in order to make students more comfortable with accessing these resources throughout their college careers, and for the center to care for a student’s mental health throughout all four years. Kraegel did mention that the center has considered something like this in the past.

Marissa also noted that after moving off campus, she feels less connected to resources on campus, the center included, and that more outreach could be done towards upperclassmen to maintain those connections.

Whether or not this care is best found in group therapy sessions may be up to the individual. However, Kraegel remains confident in the benefits of the group sessions. “When we recommend a group, it’s because our data shows groups are the most effective. We really believe it’s the most effective thing for a student.”

Kraegel rightly acknowledges that students might not perceive the benefits right away: “We’re still working on our marketing around that.”