Scientists have recently identified Earth’s new strongest known material: limpet teeth. Stronger than Kevlar, and surpassing even spider silk, the miniscule structure is found in a nondescript marine gastropod.

Limpets are a plain but tenacious creature, resembling nothing more than ridged conical hats. The creatures measure only about 5 centimeters (2 inches) across, and their teeth are less than 1 millimeter (0.04 inches) in length, according to Michelle Starr of CNET Magazine.

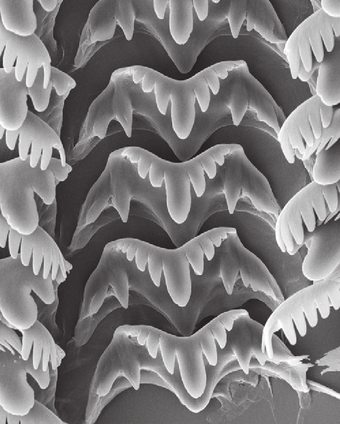

A limpet’s teeth stand in rows on the animal’s radula, a tongue-like structure for scraping the algae they eat from the rocks they live on. The tiny points are a curved shape and contain the mineral goethite.

Both the shape and the composition contribute to their prodigious strength. Goethite measures between 5.0 and 5.5 on the Mohs scale of hardness (diamond is 10) and develops in common limpets (Patella vulgata) over the course of their lifetime.

Limpet teeth are now replacing spider silk as the strongest known biological material, surpassing its strength by 10 percent, according to professor Asa Barber of England’s University of Portsmouth, the study lead.

Barber and his team tested the material’s tensile strength and found that it took 6.5 gigapascals (GPa) of pressure to pull the structure apart. According to Barber’s study, published in the journal The Royal Society, Kevlar has a tensile strength of only 3.0 to 3.5 GPa, and spider silk’s is 4.5 GPa.

Scientists have been studying spider silk for its “potential applications in everything from bullet-proof vests to computer electronics,” according to Barber. Now limpet teeth are inspiring structural engineers to think even larger: toward fibrous materials for use in automobiles, boats and aircraft.

“Nature is a wonderful source of inspiration for structures that have excellent mechanical properties,” Barber said.

This particular structure defies expectations in more ways than one. The teeth were found to retain their remarkable strength regardless of size.

“Generally,” Barber said, “a big structure has lots of flaws and can break more easily than a small structure, which has fewer flaws and is stronger. Limpet teeth break this rule as their strength is the same no matter what the size.”

Yet any limpet’s tooth is many times thinner than any synthetic nanofiber currently used in bicycle frames and bulletproof vests, according to Becky Oskin of Live Science.

This discovery is particularly relevant to engineering of vehicles—and especially high-speed ones—because the structure is both strong and light. Typically, strength in building materials implies sacrificing an automobile’s potential for speed.

Now, by imitating the design of limpet teeth, scientists suspect racing bicycles and cars can keep the structural safety provided by heavy materials without surrendering the speed achieved by lighter ones.

“It’s about translating design principles,” Barber told National Geographic. “For the next five or 10 years, this is the challenge.”