Calvin’s push to get profs 1B vaccine status met with support, criticism

Calvin, along with the other 24 members of Michigan Independent Colleges and Universities, has recently advocated for the prioritization of instructional faculty.

Instructional faculty at colleges and universities in Michigan are not included among priority groups for COVID-19 vaccination eligibility. Although several other states have given higher education faculty priority alongside K-12 teachers, only those in K-12 fall under 1B eligibility status in Michigan.

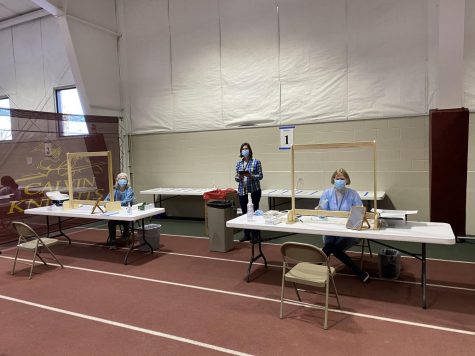

Calvin, along with the other 24 members of Michigan Independent Colleges and Universities, has recently advocated for the prioritization of instructional faculty. On Feb. 11, President Michael Le Roy presented Calvin’s case for moving instructional faculty to 1B status to the Michigan Legislature Appropriations subcommittee.

“I’ve risen every day and asked along with my colleagues these same questions: how do we persevere and continue to deliver the promise of a Calvin education? How do we make a good faith effort to deliver that mission embodied and in person?” said Le Roy.

Calvin professors have a diversity of opinions on this push to gain 1B status.

Biology professor David Dornbos spoke of the threat that being in the classroom with students (many of whom are frontline workers themselves) presents to him and his family. “I’m frustrated and kind of confused,” said Dornbos. “When I look at teachers who are K-12 being eligible, I think: so they’re in the classroom with lots of other people, is it that big of a difference in the college classroom?”

In the fall semester, Dornbos felt safer teaching class in-person due to safety protocols enacted by Calvin. The potential appearance of new strains with higher transmissibility, however, raises the risk of in-person instruction and professors’ uncertainty about safety. “When we started seeing the uptick on campus, that’s when we were first seeing the new strain in Kent County. So you don’t know—is the new strain at Calvin?” asked Dornbos.

Biology professor Anding Shen, who specializes in immunology, shares similar concerns. “You could argue that [higher education faculty] might be able to distance a little better—but as science professors, we work with students in labs. Let me tell you—in labs, it’s not possible to distance,” said Shen.

Shen argued that Michigan policy makers ought to craft more nuanced policies that acknowledge that some health care workers, such as those who work in IT or finance, don’t have patient contact. In these cases, instructional faculty at colleges and universities may be at higher risk, according to Shen. “I would even argue unless you’re working directly with patients, we have an incident rate common to any healthcare setting,” said Shen.

Some professors had a different opinion on instructional faculty’s prioritization when considering the effect this might have on other at-risk populations in the state. “I want to be vaccinated… but I think that university instructors as a class being higher priority for the vaccine than inmates would be bad policy,” said philosophy professor Kevin Timpe. “I’m well aware that university faculty being prioritized a certain way does not by itself entail anything about inmates. But I think that we also have to pay attention to the structural pressures that we could be contributing to… and we should care about that,” he said.

Dornbos agreed: “Underserved populations need to be prioritized high… If I have to wait longer to get vaccinated, then I’d absolutely do it.”

Despite the push for vaccination, Le Roy shared in the subcommittee meeting that risk of exposure in the classroom remains low. “Because of everyone’s diligence and care, the classroom has been one of the safest places on campus. It still is,” he said.