‘Antebellum’ does appearances well but lacks depth on content

This review contains spoilers.

From its initial pan from blue sky framed by Spanish moss down into an opulent action shot of almost five minutes, Antebellum is a movie about appearance. In this single shot, the director drags the audience deep into a web of well-shot violence, setting his stage in gorgeous color, juxtaposing the violence of his core material.

A strong score fades slowly into the sounds of struggle as the scene resolves into its initial conflict, an enslaved woman caught in a slow motion bid for freedom. Backlit by a gorgeous sunset, her face is a streak of sweat and desperation as a noose drops over her neck and she falls backwards on the road. “Kill me,” she whispers to the main antagonist, as he pushes her farther to the dirt with his foot, “kill me.”

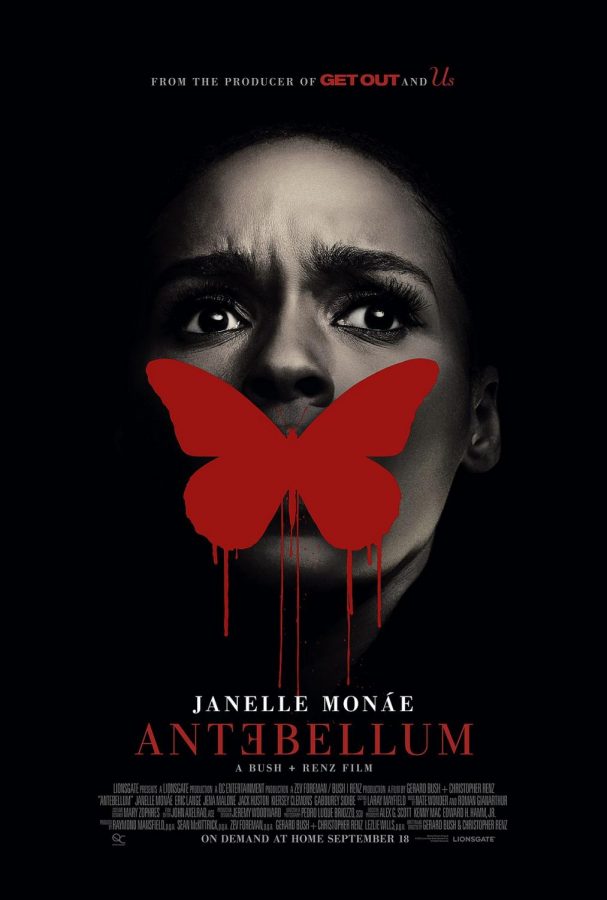

Poorly received by critics, the movie currently sits at 5.5/10 on IMDb and only 27% on Rotten Tomatoes. Touting itself as a film from the “producers of Get Out and Us,” ground-breaking works by Jordan Peele, the film fails to live up to the precedent set for it. What value Antebellum holds is in its gorgeous cinematography, rather than its content.

The first half of Antebellum sets up a beautifully shot movie, lingering scenes framed in fantastic ways and driven by a stellar performance on the part of Janelle Monàe. The film is lavish, almost heavy-handed in its cinematography. Visuals aside, Antebellum has little merit as a relevant or thought-provoking race-based movie.

Leaning heavily into the racial and political pulse of modern-day America, directors Gerard Bush and Christopher Wenz, civil rights activists themselves, flip the traditional “slave story” script in an attempt to create a relevant story. Around the one hour mark, after setting their stage in the Antebellum period on a cotton plantation, the filmmakers reveal the plantation to be an epic cosplay, white men and women in costume and generic accents, reenacting the ugliest of history. Black men and women are kidnapped from their 21st-century lives, forced into positions of servitude, beaten, and raped.

Beyond this shocking turn of setting, the film has little to offer. A storyline handling such delicate and meaningful subject matter is expected to have some deeper level of merit, something Antebellum lacks. In an era where the fight for equality is becoming repetitive, Bush and Wenz’s film fails to say anything new, instead leaning into stereotypical roles and caricatures of feminism and anti-racism.

If taken only as a horror/thriller film, well-shot and acted, Antebellum could hold its own until its final quarter. The film devolves into a hashed and uneventful ending, a gorgeous but ultimately meaningless push to say anything relevant. A fight between Janelle Monàe’s character Veronica and one of her rival female characters moments before the movie’s end feels like a forced show-down between two women and a hackneyed attempt at meaningful dialogue when Monàe’s character asks in a scream “What kind of woman are you,” a phrase that rings hollowly with the rest of the movie.

Antebellum’s beauty is only skin deep, beneath the surface it begins to feel like a farcical attempt at relevance. The racists central to the violence of the film were creating a lie of a world that was based on appearance, and unfortunately the film’s creators tread dangerously close to doing the same. While not every film needs to be more than visually appealing or have a “deeper meaning,” Bush and Wenz created a world so close to our own that it lends itself well to political commentary, however Antebellum’s lack of follow-through makes it fall flat. The real-world issue of racism that Antebellum handles is more than a surface-level problem, and the film fails to offer more than a surface-level reading of its material.