Black students question effectiveness of Calvin’s summer response to BLM

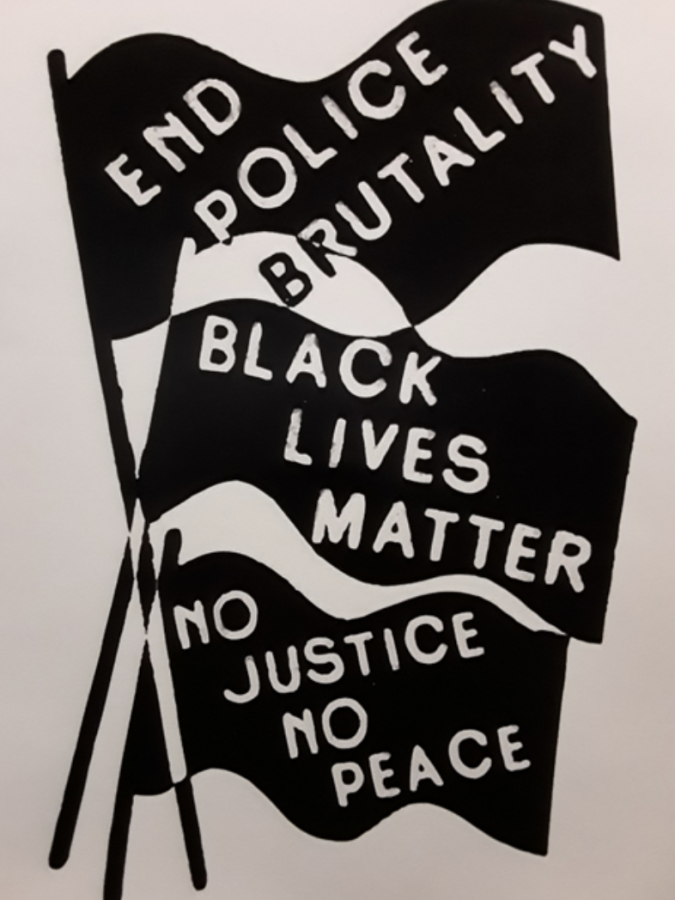

A poster supporting the Black Lives Matter movement found on the Grassroots floor.

Five days after the murder of George Floyd, Calvin University President Michael Le Roy issued a statement condemning the act of police brutality and declaring Calvin’s firm antiracist stance. An hour-long panel discussing race and faith followed the statement as well as a 15-minute video in which several Calvin professors echoed the phrase “Black Lives Matter.” But questions remain about whether this response was enough.

For Black students like Jacob Williams, Ehmani Horton-Flowers, and Shaneel Kenyon, words alone were not good enough, and the timing was disappointing. To them, the tardiness of Calvin’s response was painful.

The sudden spread of coronavirus made the spring semester difficult enough for most students. For Williams, a computer science major, having to go back home unexpectedly and form a new routine was a stressful experience. A sophomore majoring in political science, Horton-Flowers also struggled to adjust during the online segment of the spring semester. Kenyon, a senior majoring in exercise science shared her disappointment in having to cancel all the events she had planned for the semester as a Multicultural Activities Coordinator (MAC) intern. However, in spite of the life changes these students faced, they were not spared the reminder that police brutality is still an ongoing problem in America.

For all three, the news of George Floyd’s killing was hurtful but not shocking. Williams spoke about how familiar this experience was for him. He was in sixth grade when Trayvon Martin was killed by the police.

“It’s the same old song and we sing back to it ‘who’s next?’” said Williams.

For him, it is a very real experience, as he has had friends and peers in his community who have been arrested. He expressed a deep thankfulness that none of them had been killed in police interactions and spoke about developing a survival mentality in which he was hyper-aware of himself and his surroundings. His words reflected the fear that many Black people feel: that he could be next.

Kenyon shared a similar experience of being unsurprised by seeing another Black man being killed by the police. For her, it was frightening to watch the video of Floyd’s death and see the blank expression on the officer’s face. She described feeling angry about the constant lack of justice and taking these feelings to social media. Eventually, she had to take a break.

Horton-Flowers mentioned being tired overall but was surprised by the support for opposing groups such as Blue Lives Matter and All Lives Matter and critiqued the validity of their arguments.

“They can take off their uniforms, but I can’t take off my skin color,” added Horton-Flowers.

For these students, the murder of George Floyd was personal. In watching the video of his death, they could see the members of their communities, their loved ones, and even themselves.

These students felt that Calvin University’s statement was too late in their time of hurt.. The five days between the murder of George Floyd and the Calvin response may seem trivial, but the Black students Chimes spoke to said it mattered to them. According to Williams, this lateness reflected a lack of urgency when it came to the feelings of minority students, faculty, and staff.

According to history professor Eric Washington, Le Roy was away when the incident occurred.

Regardless, students were left unsatisfied. Kenyon mentioned how Calvin staff of color were quick to respond to the incident and reach out to students, particularly citing the Sister 2 Sister (a support group for Black women on Calvin) Instagram page as a good example of this. In her perspective, a short immediate response followed by the longer response would have been more effective.

Horton-Flowers echoed similar sentiments of being unsatisfied by the response. It seemed performative at best, in her opinion. In Calvin’s statement, Le Roy mentioned upholding the From Every Nations (FEN) document, which promotes antiracism. Although this document was adopted in 2004, Horton-Flowers found her experience at Calvin to be marked by racist encounters including microaggressions and on one occasion being referred to by the n-word. Although Williams mentioned that the university reached out to him individually, Horton-Flowers and Kenyon did not receive the same treatment.

“Antiracism is not debatable on a Christian campus,” said Washington.

When asked about what the Calvin community could do to be better, Washington mentioned antiracism as an integral and pervasive part of the core curriculum. Kenyon and Horton-Flowers echoed similar sentiments of educating both faculty and students on antiracism, particularly by making Unlearn Week more expansive and compulsory. Williams expressed that more of the diversity of Grand Rapids should be brought into Calvin. To Williams, Horton-Flowers and Kenyon, it is important that Calvin, as a Christian university, continuously echoes antiracism as part of God’s call to love your neighbor.

To these Black students and others, “Black Lives Matter” is more than a slogan. It is a phrase of empowerment and endearment.

As Williams said, “It means that we are here. We live here with everyone else, just like everyone else. We can do the same thing as everyone else can do. We are no better or worse. We love each other just the same as everyone else does.”

Ruth TenBroek • Sep 19, 2020 at 12:43 am

Yes, quite disappointed with Calvin University’s late response. Calvin has been an integral part of my life, and expected much more. Better late than never I suppose, but they needed to be clear with their support right up front.