New book on decadence glimpses to its own failures

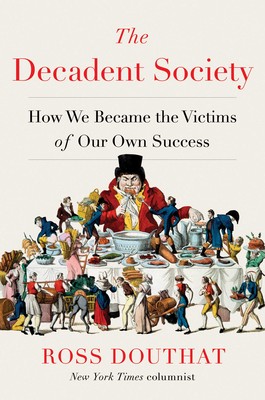

Cover photo from Simon and Schuster. Fair Use.

Douthat’s book against decadence indulges in a little decadence of its own.

Ross Douthat’s new book, “The Decadent Society: How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success,” critiques the West’s fall into decadence — and in the process, he makes a few decadent claims of his own.

A society riddled with decadence has reached “economic stagnation, institutional decay, and cultural and intellectual exhaustion,” according to Douthat, because of its material success and technological development. Simply put, the West, now in a period of extended stagnancy, has become a victim of its own success.

To Douthat, the “Götterdämmerung,” or twilight of the gods, was Apollo 11. After Apollo, we have metaphorically, and literally, stopped reaching for the stars. All has been stagnant at best, downhill at worse, since July 16, 1969. Neo-liberal politics have failed, and there is a possibility that “hope does not exist, that there is quite literally nowhere else for mankind to go.”

When Douthat mourns pre-decadent America, he also mourns a more deplorable one — one where all races weren’t equal in the eyes of the law, where endless wars were the norm, where dictatorships flourished.

Regressive responses such as the possibility of a eugenics war are technically responses to decadence, even if they are poor responses, Douthat claims: “we might be moving in a dangerous, even wicked direction, but we would be moving.”

The same can be said of intense police states that rule with neoliberal ideals, or a return to paganism. At this point, an empathetic reader should agree with Douthat that these responses are not desirable, but should perhaps disagree that this would put an end to decadence. Moral and cultural decline would intensify, so perhaps responsible readers should reject his definition of decadence.

The most significant strength of “The Decadent Society” is its audience awareness. Although Douthat is an establishment-style conservative who also writes for William Buckley’s “National Review,” he demonstrates an awareness of his more liberal readership, allowing for more effective persuasion.

Most notably, the chapter on sterility demonstrates this — the world’s richest countries aren’t reproducing at a rate that can successfully replace the existing population. Instead of using the traditional conservative and religious ethical arguments, he persuasively argues that the hypersexualiation of the 20th and 21st centuries has created a less-sexual culture. “People reacted to the social revolutions of the 1960s first by marrying less and divorcing more and having fewer children… [and even] having less sex, period,” he writes.

Ironically, one of Douthat’s signposts of decadence is the repetition and recycling of ideas, which he falls prey to himself. At one point, he uses the overabundance of superhero movies to corroborate his claim that the West has hardened its moral and cultural decline — this claim, even if true, is a less interesting version of Martin Scorsese’s critique of the copy-and-paste formula followed by many mainstream movies. In this sense Douthat’s own book can serve as an example of decadence, at least by the dictionary’s definition of “moral and culture failure,” if not by his own.