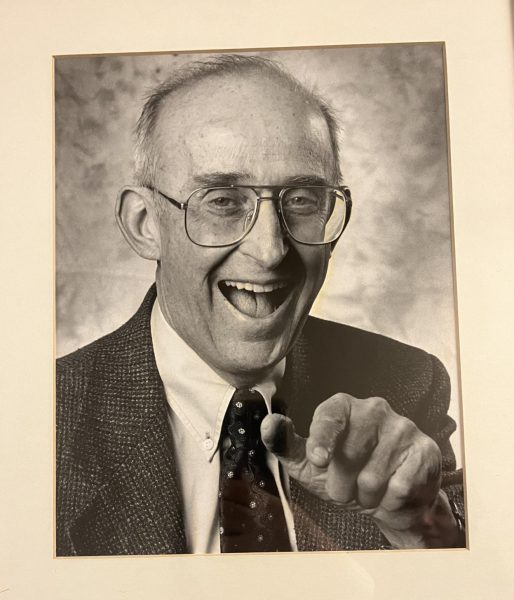

Co-founder of AJS helps eradicate police corruption in Honduras

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the current homicide rate in Honduras. The figure has been corrected below.

On Thursday, April 11, Carlos Hernández came to Calvin to speak on the work the Association for a More Just Society, an organization he co-founded, has been doing. AJS explores the idea of how to create a more just reality in Honduras. In April 2016, Hernández and his team did just that, tackling police corruption in Honduras.

“[A]ll of us have the need to feel safe, and in every country, there is a system of police that are designed to keep people safe… one of the biggest problems a country could have is when the police turn into aggressors,” Hernández opened.

The problem of police corruption in Honduras is massive, and until recently the country held the highest homicide rates in the world. The corruption also allows for more drug trafficking in the country, and this problem is enhanced by Honduras’ Central American position in a main artery for drugs moving north from South America.

“All of the drugs, mostly cocaine from Colombia, pass through us,” said Hernández. As a result, the “feeling of insecurity grows when the police can’t be trusted.”

A tragic story stemming from this fear of the police eventually put great change into motion.

Hernández shared a story of two young men leaving a party who tried to flee the police. The officers caught up with them, intending to steal their car. After the officers recognized that the young men had powerful parents, one’s mother being a well-known political figure, the officers saw their problem. They took the young men to a secluded spot, and, at the command of their supervisor, the officers shot both men.

Once in the media, the story caused an uproar. The murder of people with status forced the government to pay attention to its problem of police corruption. This atmosphere gave AJS the opportunity to step in.

Hernández and his team started out confused, asking, “‘What can we do, what can we do?’ We felt helpless, like we were losing our country and youth of our country.”

AJS started publicly sharing the names of officials who allowed police corruption to happen. They acquired countless testimonies to learn “how the police had organized to carry out many high level assassinations of those who opposed police forces,” Hernández stated. AJS went to newspapers, TV news and public forums, anywhere to get the word out. In April 2016, they succeeded: AJS was able to publish in the New York Times an article showing the most prominent criminals in Honduras’ police corruption ring. This article garnered international attention.

“We gave faces to the criminals… [finally] the government was forced to respond… the only problem? No one believed in the government.”

Nearly two years ago to the day, Juan Orlando Hernández, the president of Honduras, called Hernández, asking for his help. Fearfully, Hernández chose to accept the president’s request, and together they formed a commission for purging the police force.

“It was the biggest challenge of my life and the biggest challenge for our organization… taking on this task meant that we were standing up to the most powerful and the most violent people in Honduras… not just the police, but the people that the police were working for… leaders in drug trafficking, the private sector, and politics,” Hernández explained.

Challenge aside, this commission had wild success. Over 5,000 officers were purged from the Honduran police force, and a new training program was set in place. Training increased from three months to a year. Candidates now need to have a high school education instead of only a sixth grade one. Additionally, the homicide rate in Honduras has dropped from 86/100,000 to a level of 43.6/100,000 today. While this number is still not to their goal of 28/100,000, and well above the global average of 6.2, Hernandez says the progress should be applauded and shows hope for the future.

“I think Honduras can become a place of peace… and, most importantly, that Christians understand that we can be agents of change in the world… even though we’re not experts, with God, we can do it.”

If students would like to learn more about AJS and their continuing work, they can find the organization on Facebook or at https://www.ajs-us.org/.

Carlos Arias • Apr 26, 2018 at 6:10 am

Colombia* instead of Columbia.