Gentrification in the Heartside Community questioned

ArtPrize is one of many initiatives that have brought an influx of artists, tourists and businesspeople into downtown Grand Rapids over the past several years. This area — also known as Heartside Community — has been revitalized since the early 2000s, though local scholars and organizations have mixed views on whether these changes have manifested in gentrification and whether gentrification is itself a problem.

Starla McDermott of Guiding Light Ministries on Division Street remembers a different Grand Rapids ten years ago. McDermott remembers, “…a lot of crime, some prostitution, people didn’t come out at night, people didn’t feel safe. I feel like it’s more diverse now. There are business people who live here as well as […] a homeless culture here.”

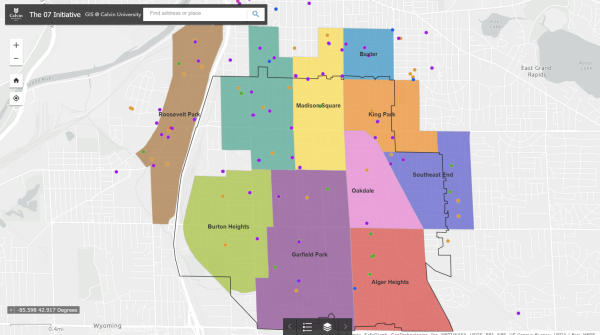

According to local urban sociologist and GVSU professor Joel Stillerman, the transformation of downtown Grand Rapids can be traced to a 2004 Cool Cities grant which encouraged more artists to settle in the Heartside community. As artists integrated into the neighborhood, they unintentionally made the area “feel safe and more appealing to wealthier folks and developers.” Heartside became a mixed-income area bolstered by developers, investors and new businesses.

“The question becomes,” said Stillerman, “Is the area going to remain liveable for the local population or is the character going to change so much that the people who were living there before don’t feel at home in their own neighborhood?”

Data indicates that as Grand Rapids has developed, there have been changes in housing costs and rates of homelessness. The 2015 US Census reports that while the median household income in Grand Rapids increased five percent between 2010 and 2015, the median rent increased 33 percent in that same time, creating disparity between income and living costs. Additionally, the Grand Rapids Area Coalition to End Homelessness found that there was a 15 percent increase in the number of homeless people from 2014 to 2015.

“It is pretty widely accepted among urbanists that one of the key drivers of homelessness is the mismatch between average wages and average housing prices,” Stillerman told The Rapidian. Increased housing costs, stagnant wages and rising homelessness are often indicative of gentrification, which occurs when a community conforms to middle-class standards and tastes but becomes unaffordable for original residents.

Stillerman said that ArtPrize may be a contributing to the larger phenomenon of gentrification. He said the event labels Grand Rapids as a tourist destination and is “a huge [booster] shot in the arm for any business downtown.”

Brooke Jevicks of Dégagé Ministries, also located on Division Street, agrees that “ArtPrize impacts the city tremendously” by increasing tourism and producing economic stimulation for local businesses.

Yet while Stillerman characterizes growing businesses and other signs of revitalization as problematic for low-income populations, Jevicks, who works for a ministry serving homeless and low-income communities, says that the economic development in Grand Rapids and on Division Street is “not a negative thing” but is “the neighborhood growing and building.”

McDermott, who also serves low-income and homeless individuals in Downtown Grand Rapids, agreed with Jevicks that growth in local businesses was beneficial to the community. She went on to say that the existence of low-income housing options was evidence that gentrification was not occurring in the Heartside area.

On the other hand, Stillerman said that rising housing costs and increased homelessness is a problem that is not restricted to the downtown area:

“Heartside is just a microcosm, maybe an extreme one, of what’s going on throughout Grand Rapids.”

Stillerman said that equitable redevelopment “would require some very strict regulation of rent and housing cost” in order to ensure that revitalization does not lead to gentrification.

For their part, nonprofits like Dégagé and Guiding Light are committed to staying in Heartside and serving residents, making sure the people they serve still have a place to go.

Jevicks said, “We believe that a healthy community is all of us working together, no matter what’s happening… [and] if developers see this area as a growth opportunity in the city, that great, we just can’t forget about the people who were here first.”