Calvin student Grace Maurer and Calvin alumnus Ari Vangeest led teams of surveyors last fall to study racial bias in Grand Rapids policing.

The results of their study, which found that black drivers are about twice as likely as white drivers to be pulled over by Grand Rapids cops, were released last week in a series of town hall meetings in the community.

The city of Grand Rapids hired Lamberth Consulting, a national leader in racial bias research, last year to assess racial profiling of motorists by the Grand Rapids Police Department (GRPD). Maurer, a sociology major, and Vangeest, a 2016 graduate of the sociology program, were hired to be Lamberth’s “on the ground” team leaders for the study.

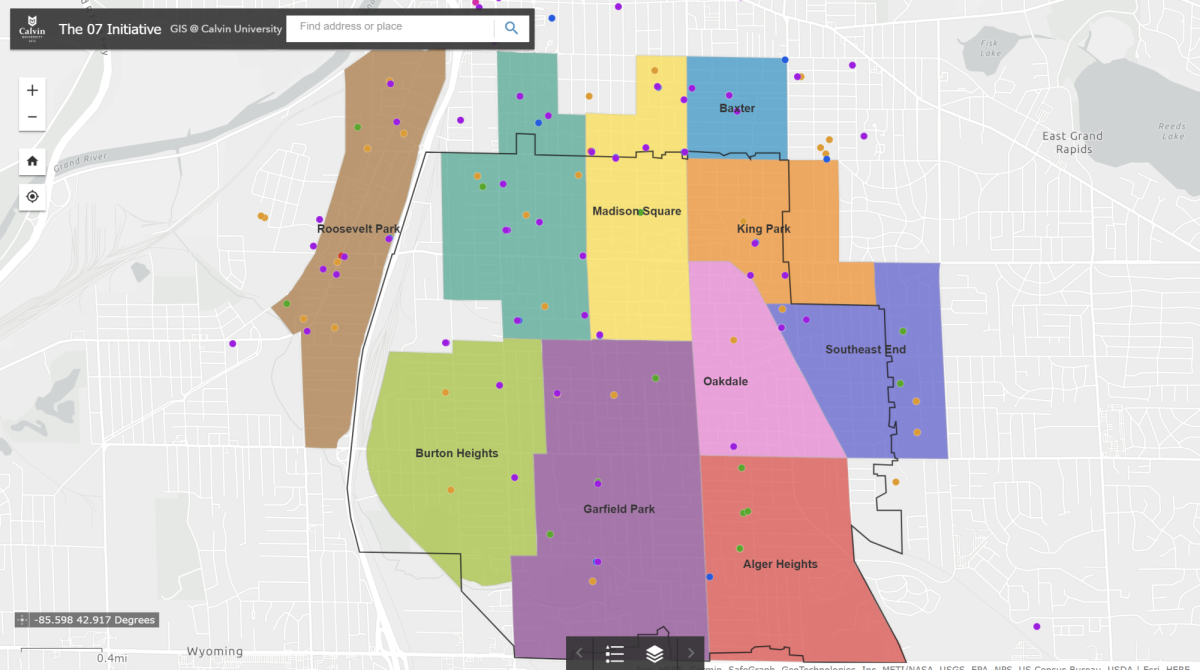

The study determined bias by comparing the racial makeup of the traffic through 20 city intersections against police data about traffic stops and searches from 2013, 2014 and 2015.

It was Maurer and Vangeest’s job to gather the data about the racial makeup of drivers in each of the 20 intersections.

“It’s all about the odds of being pulled over,” Vangeest said. A common misconception about the study, Vangeest says, is that it’s about who gets pulled over more often. The police pull over white drivers more often than they do black drivers, but the key is the relationship between the percentage makeup of area traffic and the percentage of drivers that are stopped by cops.

Maurer and Vangeest described the study as “well-designed.”

“One reason the study is so good is we’re not just looking at census data, we’re looking at the transient population,” Maurer explained. Census data would show who lives in the neighborhood around the intersection, but those who drive through a neighborhood are not always the same population as those who live there. Vangeest and Maurer mentioned how much of a difference there was between the weekend traffic of young adults driving downtown to go to the bars and the weekday traffic of people commuting back and forth to work.

The Lamberth study takes this into account by surveying the racial makeup of the traffic at each intersection. Maurer and Vangeest were in charge of organizing teams of four to stand at intersections for four-hour shifts and tally the race of drivers who passed through the intersection.

They used a number system to quickly mark the race of each driver. Maurer said she felt uncomfortable at first putting people into categories that the drivers might not personally identify with, but she realized that, in order to study racial profiling, she would need to put herself in a mindset of an average person’s assumptions based on appearance.

The surveyors also used bright lights at night to help them identify the race of drivers. In general, despite high volumes of traffic, the surveyors were able to identify race 97.8 percent of the time, marking “unknown” or “ambiguous” for just 1,259 out of the 57,660 vehicles counted in the study.

These tallies were compiled by Maurer and Vangeest, who sent the numbers to Lamberth Consulting, based in West Chester, Pennsylvania. Maurer and Vangeest were the only Lamberth employees on the ground in Grand Rapids for the duration of the data collection.

Analysts at Lamberth then compared this data to 2013, 2014 and 2015 traffic stop data provided by the GRPD. The traffic stop data included not only information about the race and gender of drivers pulled over by the police, but also information about the kind of searches conducted and whether or not the officer found contraband in those searches.

Vangeest said that the data about police searches results contradict a common argument he hears from people who disagree that racial bias is a factor in police practices. Though black motorists were 2.54 times more likely to be searched than white motorists in 2015, the “hit rate,” or the rate at which a search turned up contraband, was approximately statistically equivalent (around 25 percent) for blacks and whites in Grand Rapids. This, for Vangeest, suggests there is “no way that you can say that black people just commit more crime” than white people.

One methodological problem Maurer and Vangeest ran into was the categorization of Hispanic drivers. Since the early 2000s, the police have not categorized Hispanic as a unique race in their data collection, whereas for black drivers the police indicated that categorization in their data. To determine the odds ratio for Hispanic drivers, the researchers looking at the police data had to use the last names of drivers to guess at their ethnicity.

The researchers found that Hispanics overall are stopped at an odds ratio of 1.3, which Lamberth categorizes as benign, though still above the odds ratio of 1 which would indicate that they are pulled over at rates proportional to their presence in the intersection.

Maurer and Vangeest spent significant amounts of time with police while collecting data for this study. The consulting firm used the police to provide protection for talliers, especially at night, and also used the police to drive Maurer and Vangeest, the supervisors, around to collect data from the talliers.

Maurer emphasized that though she felt uncomfortable occasionally, most of the interactions she witnessed or experienced with officers were positive. She said “lots of people asked the cops for directions” while she was riding along with them, and there were lots of positive interactions between community members and police. This surprised and impressed her, especially when these positive interactions occurred in low-income areas where police and community relations are sometimes strained.

Yet both Maurer and Vangeest noted the growing divide within the police between officers who are open to programs like implicit bias training and those who feel attacked and defensive about racial bias studies like this one.

Maurer said that she drew hope from the fact that many of the surveyors she worked with to collect the data were in training to become police officers. It gives her hope that future police officers are invested in the problem of racial bias and want to understand its extent and implications.

The study backs up anecdotal evidence of racial bias in policing. “A lot of people’s reactions were just like, water is wet, we already knew this,” Maurer said. “It’s their experience, and this just reinforces their experience,” Maurer said of minorities in Grand Rapids. But the study is significant because the experience of minorities is “still being dismissed,” Maurer said, while empirical evidence is less easy to dismiss.

Vangeest said he still gets accused of fabricating or skewing the data with a liberal bias, even though he notes that he couldn’t have done so if he had wanted to. “We didn’t have any data from [the police] before starting the survey,” he said, and since the study compared current demographics with already-recorded police data, neither he nor the police department could have attempted to change the data in anyone’s favor.

Both Vangeest and Maurer framed the study in the context of what Maurer called “the militarization of the police” and the “divide” between the police and the communities they are charged with protecting.

“Some people see this study as another attack on the police,” Vangeest said. “But I didn’t come into it thinking that at all … I was thinking we can address this problem with empirical evidence; we can change this.”