In some of the first bills introduced this year, Michigan lawmakers are looking to wipe out the personal income tax with proposals in both the House and Senate.

The Michigan House’s Tax Policy committee approved a bill Wednesday that would eventually eliminate Michigan’s income tax.

The bill would start the phase-out with a decrease from the current flat-tax of 4.25 percent to 3.9 percent by Jan. 2018. Each year after that, the income tax would be lowered by 0.1 percent until the tax is eliminated entirely by 2057.

A much more aggressive elimination plan was introduced in the Senate by Sen. Jack Brandenburg of Harrison Township on Jan. 18.

Under Brandenburg’s Senate Bill 0004, Michigan’s income tax would be no more by 2022, by way of a plan that would first lower the income tax to 3.9 percent and then slash the tax by 1.0 percent each subsequent year. More than a dozen senators co-sponsor the bill, which is now in committee review.

The number 3.9 percent, featured in both proposals, comes from a 2007 promise that the tax rate would eventually settle at 3.9 percent after the recession-era increase of the state income tax to 4.35 percent.

Michigan is not the first state to experiment with eliminating the income tax. Currently, Florida, Texas, Wyoming, South Dakota, Nevada, Alaska and Washington do not levy income taxes on their residents.

In his case for the bill, Sen. Brandenburg pointed to concern over Michigan’s population, which over the past few decades has always decreased or remained stagnant. Brandenburg argues that the income tax phase-out will keep Michiganders in-state and attract new businesses and workers to the state, triggering economic growth that will replace the lost revenue.

Michigan’s income tax, which is at a flat rate for all residents, is currently at 4.25 percent, the 11th lowest state income tax in the country.

Despite the state’s comparatively low tax rate, Brandenburg argues, “Michigan is still a tough place to do business and I think the more jobs you create, it sends off a more positive image of our state. It’s simple, the more jobs you create, the more people spend. The more people spend, the more jobs are created and there is more tax revenue for our state.”

Rep. Lee Chatfield, the main sponsor of the House bill, framed his bill as a way for the people of Michigan to reap the rewards of some of the state’s recent growth. “I believe there’s no better time than now that we, as legislators, give our constituents across the state meaningful tax reform,” Chatfield said.

However, both bills face unresolved concerns about balancing the state’s budget with the proposed loss of revenue.

According to the state Department of Treasury, Michigan’s income tax brought in a revenue of $9.37 billion to the state’s general fund last fiscal year. That number, according to the department, makes up 90 percent of the state’s general fund budget.

Under the House bill, the state would lose $680 million in revenue in the first year of implementation and $1.2 billion in the next. After that, the 0.1 percent decreases would continue to cut the state’s income by around $400 million a year for the next 38 years, according to the House Fiscal Agency.

According to The Grand Rapids Press, “Chatfield deferred all questions about how to replace lost revenue to the House Appropriations Committee, saying they would ‘make it work.’”

Gilda Jacobs of the Michigan League for Public Policy testified in opposition to the House bill while it was under review in the House committee.

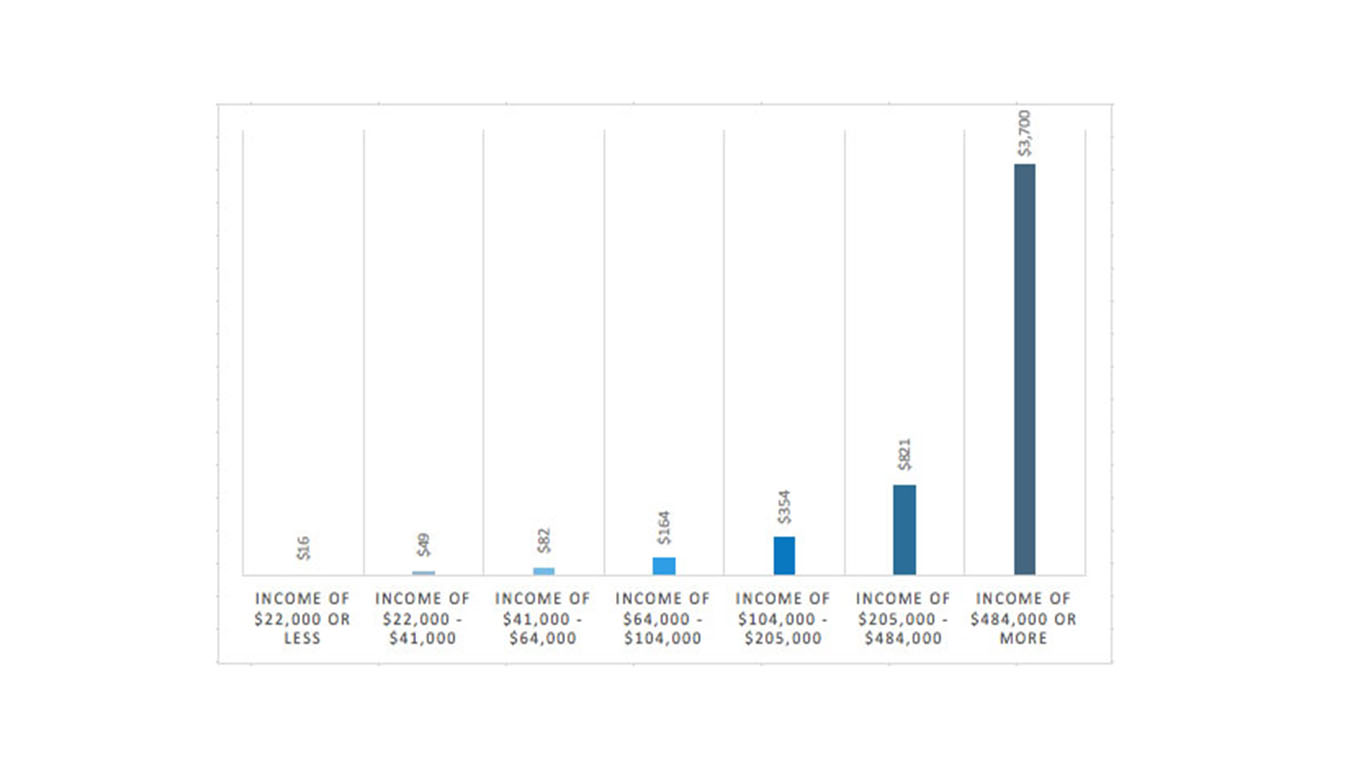

Jacobs argued that the tax relief would be disproportionately greater for the wealthy and would offer negligible relief for the poor, while gutting vital state funding for public programs.

She cited a study by the nonpartisan Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. According to ITEP, under the first tax cut from 4.25 percent to 3.9 percent, the tax relief for those earning less than $22,000 a year would be a mere $16 per year. Those who earn Michigan’s average yearly income, $51,000 a year, would recuperate $82 per year.

In response to this number, Chatfield quipped, “To the working man, that is something that they will feel.”

Jacobs argued that personal relief is not worth risking the programs the cuts will defund. “It will leave our state unable to invest in our schools, colleges and universities, communities, infrastructure, healthcare and public safety — the things that actually fuel economic growth,” Jacobs said.

Chatfield’s bill now awaits a full vote in the House.