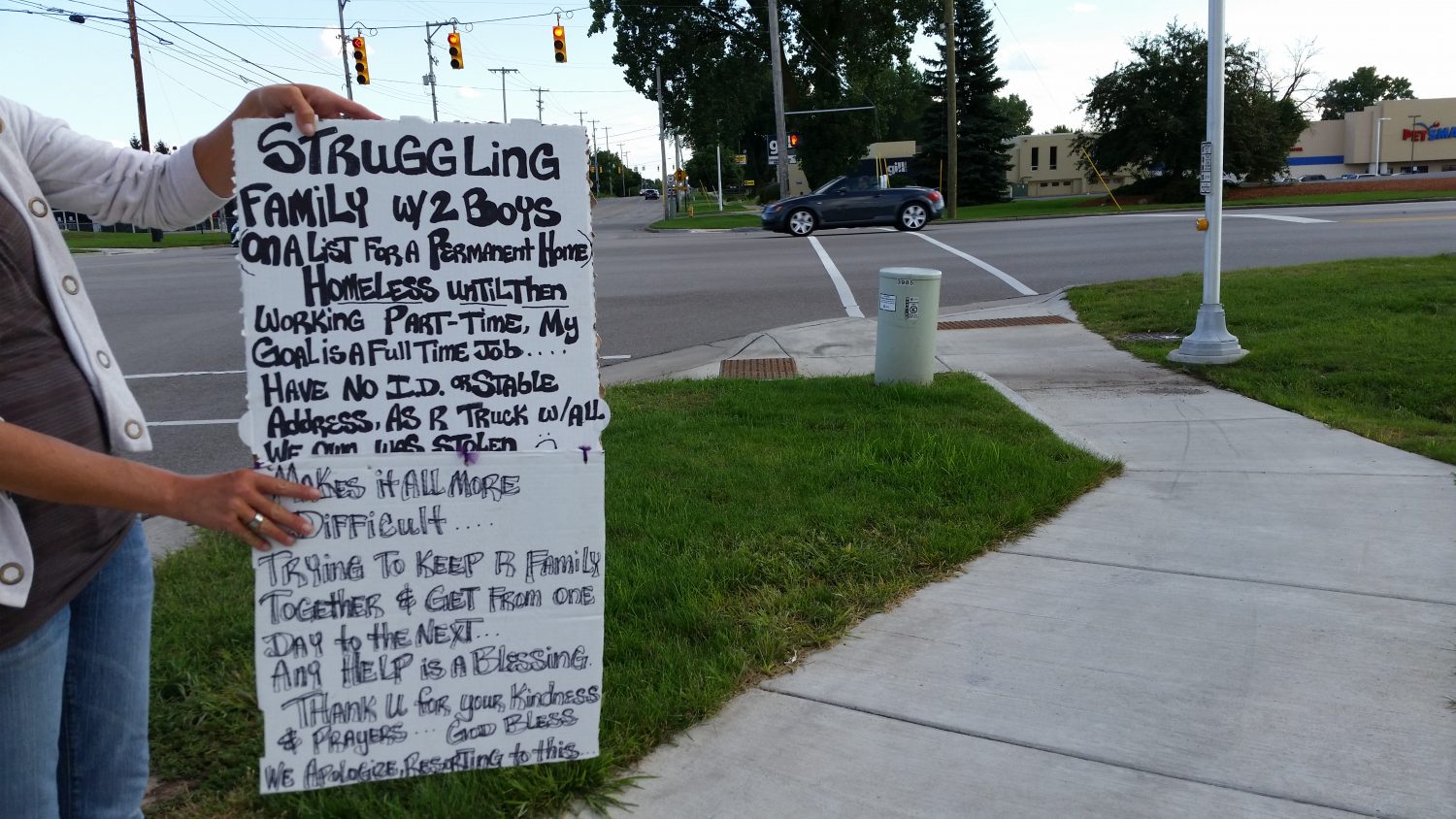

On the corner of East Paris and 28th Street in Grand Rapids is a woman named Gene. She holds up a long sign explaining that she is a mother of two boys and homeless, while working a part time job. But her goal is having a full time job, which she can’t get because she lost her ID and birth certificate when her truck was stolen.

At the end of her message she writes: “We apologize for resorting to this.”

Every big American city has its panhandlers — people who beg for money on the street. They stand on street corners and on medians with their cardboard signs that explain their situation in hopes you will spare them a few dollars. There has been a recent push to get rid of this practice in west Michigan.

In 2008, Michigan passed a law criminalizing peaceful panhandling. The state was concerned about safety, traffic and fraud.

Gene is aware of panhandling politics going on in Grand Rapids.

“I think people should have freedom of speech,” she says. “I don’t think everybody does it for the right reasons but you’re going to find that with anything.”

She explains how difficult it is to go out and ask for money.

“I don’t enjoy getting up and doing this,” Gene explained. “If I didn’t, we would literally be outside.”

Many panhandlers were arrested while the law was in effect from January 2008 to May 2011. Among those arrested were James Speet and Ernest Sims. With the help of the American Civil Liberties Union, Speet and Sims sued the city of Grand Rapids and won on the grounds that it violated the first amendment.

But the ruling was appealed. The city and state stressed its concerns about safety and fraud. The appellate court upheld the original ruling.

Boyce Martin Jr. explained his reasoning in a 17-page ruling.

“[B]ecause it prohibits a substantial amount of solicitation, an activity that the first amendment protects, but allows other solicitation based on content,” Martin wrote.

This past May, the issue arose again. Grand Rapids city officials proposed to restrict panhandling by making it illegal to ask for money from motorists, along with other restrictions that included minimum distances from ATMs and bus stops.

But the ban failed when city commissioners came to a tie vote in June and no restrictions were made.

Since then, the residents of west Michigan have been pushing to put an end to panhandling in the state. A Facebook group called “West Michigan Hardly Homeless Panhandlers” formed and currently has over 4,000 members.

The group’s mission statement is written in their Facebook page.

“Quit giving to the corner and donate at your local mission to help the real homeless,” the page reads. “Time, money and supplies are needed at all homeless shelters. Do your research and make an educated decision to donate your dollar to an organization that gives back to the community!”

Others argue an anti-panhandling law criminalizes people for being poor and inhibit their right to free speech.

In response to the Facebook group, Gene explains that shelters aren’t a place she wants to take her family because of all the drug and alcohol usage.

“There are a lot of worse things I could be doing,” Gene said. “I’m not stealing from anybody. I’m not robbing people. I’m not begging or knocking on people’s doors… You choose to help me or you don’t and that’s fine.”