For residents of the United States, the problem of human trafficking seems like an important, though distant, issue.

However, an outreach ministry called the Manasseh Project, run by Wedgwood Christian Services, has set out to inform the general public that human trafficking might not be as distant as many Americans believe.

During this year’s ArtPrize, the Manasseh Project will take to the streets and broadcast its message on a grand scale.

On a global scale, the figures relating to human trafficking are staggering. A U.N. estimate holds that between 700,000 and 4 million men, women and children are recruited, transported and harbored by force or coercion for the purpose of exploitation involving commercialized sexual activity or forced labor.

This exploitation forms the basis for an industry which rakes in upwards of $7 billion annually.

This industry makes its mark domestically as well as internationally. According to the U.S. State Department there are an approximate 1.8 victims of forced labor or commercial sexual exploitation per 1,000 individuals living in the U.S.

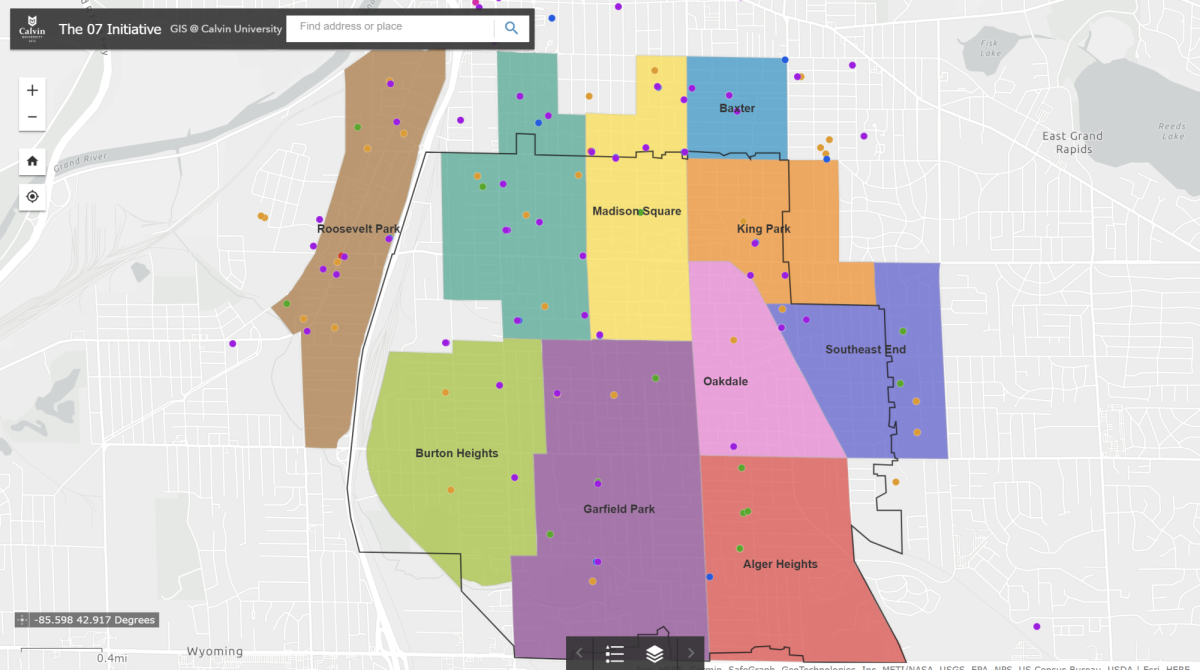

This is where the Manasseh Project comes in. Seeking to draw attention to human trafficking in the West Michigan area, the Manasseh Project takes the figures provided by the U.S. State Department and uses them to form a ratio. Assuming this ratio, there may be as many as 2,379 residents of Grand Rapids, Holland and Muskegon who are trafficked annually.

But those working for the Manasseh Project have found that it often takes more than posting big, scary numbers on their webpage to move people to action.

The Manasseh Project itself began not with the reading of some statistics, but as a result of a real life experience. Andy Soper, Wedgwood employee and the Manasseh Project’s program coordinator, encountered a young girl who would come to change his life forever.

“She looked just like a normal 13-year-old girl, but she was being sold eight to 10 times a day for sex,” said Soper. The girl to which Soper refers was brought by the police to Wedgwood Christian Services, an organization which devotes itself to fighting sexual exploitation, where Soper worked at the time.

Shortly after arriving, the girl ran away from Wedgwood Christian Services and returned to her trafficker, which affected Soper greatly.

“Something about her broke my heart. It’s devastating. She was all I could think about,” said Soper. “There was no turning back at that point.”

After spending many sleepless nights trying to track the girl down, Soper began to look into human trafficking. This research laid the groundwork for what would come to be known as the Manasseh Project.

Today, Soper works through the Manasseh Project to try and prevent incidents similar to the one he experienced with the runaway girl. The Manasseh Project works to fight human trafficking on a number of different fronts; members work to instruct public servants working in the education and justice systems to be first responders to human trafficking, as well as to develop youth centers and victim shelters for the purpose of serving those who have been exploited.

Soper does not remain content to deal with human trafficking only after it occurs, though. One of the biggest goals of the Manasseh Project is to prevent human trafficking from occurring in the first place. In order to make this goal a reality, Soper has set out to raise awareness regarding human trafficking at this year’s ArtPrize.

The Manasseh Project’s campaign will last for the entirety of ArtPrize’s 19 days and will be conducted with the help of more than 1,000 volunteers. There are seven sites which the Manasseh Project operates, each with a piece of art which reflects a factor of human trafficking.

For instance, one piece of art might deal with poverty while another could highlight substance abuse or a broken community. In addition to standing by each of these pieces of art and discussing with pedestrians how each piece of art deals with the issue of human trafficking, volunteers will hand out 30,000 balloons and 15,000 boxes of water, all of which will have a picture of a missing individual or suspected victim of human trafficking imprinted on its side.

Following ArtPrize, the Manasseh Project plans on putting out six weeks of additional events with the purpose of giving out information about factors leading to human trafficking and providing training on prevention and how to be helpful during its aftermath.

Soper hopes that the Manasseh Project’s ArtPrize campaign might shift Americans, and specifically West Michigan residents, from being vaguely concerned with human trafficking to fully acknowledging and dealing with the issue.

“We’re getting victims, so it’s not so much a question of if it’s happening,” said Soper. “It’s how and where it’s happening and how we can work together to solve those issues.”