From “Institutes” to confessions: anonymous confessions at Calvin

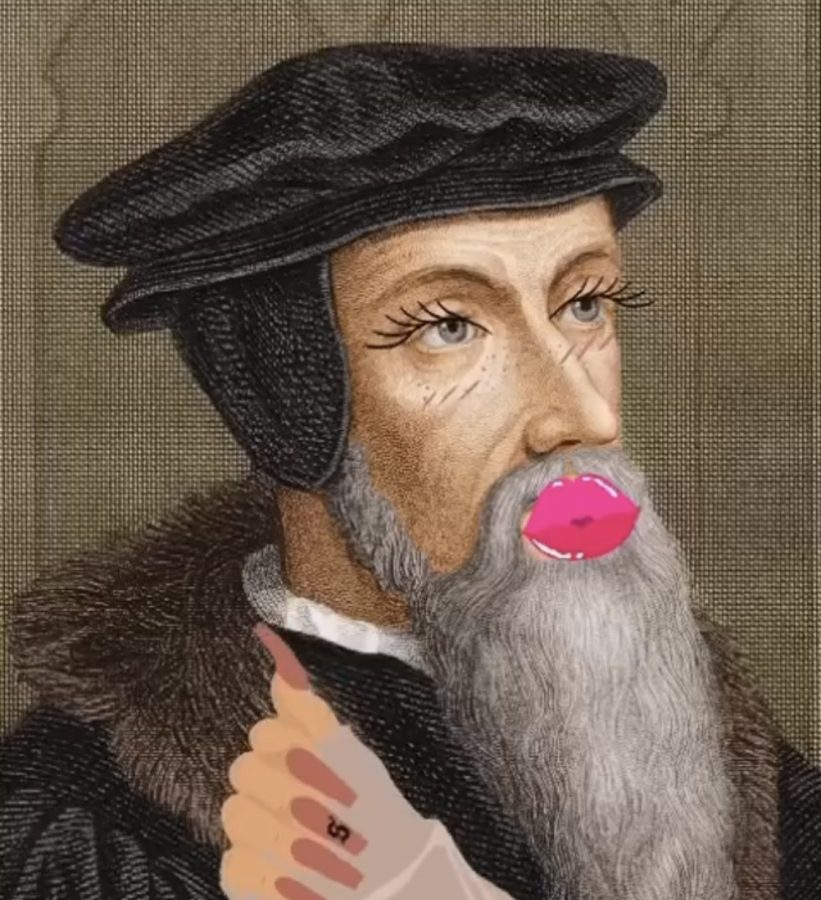

Photo courtesy of Calvin Confessions.

With this profile picture, the Calvin Confessions Instagram page takes on the persona of “John Calvin yaasified.”

“Men at Calvin be having some mad commitment issues fr fr.”

“I’m so feral for the guys that sit behind me in my stats class.”

“To the person who’s pants I spilled bbq sauce on at Johnny’s. I can never get over the shame I’ve brought upon my family.”

You can find these posts and more on the Calvin Confessions Instagram account, which shares a range of personal secrets that are –– ostensibly –– penned by Calvin students. The process is simple: Students submit their confessions anonymously via a Google Form or Instagram direct message. Then, these confessions are posted verbatim to the Instagram page for all to see. The account has almost 800 followers, which comprise current Calvin students and some alumni, and its posts regularly receive several comments and over 100 likes.

“It’s like an anonymous room to share crazy experiences,” said Calvin Confessions. The account is run by two Calvin seniors, who sat down for an interview with Chimes. These students declined to share their names in case of adverse consequences, but Chimes has confirmed their identities.

While the students who run the account see it as a fun and harmless way to connect other students online, the people who submit the posts are real, the people named in the posts are real, and the account can have real consequences.

The appeal of anonymous accounts

Calvin Confessions is not the first account of its kind: Confession accounts are popular at schools across the nation, and Calvin University itself has had several, including Facebook’s Calvin Crushes and a now inactive first iteration of a Calvin Confessions page on Instagram.

“I think [the appeal of such accounts] somewhat reflects distrust in the mainstream institutions made to deal with confessions like this,” said Craig Mattson, professor of communication and Calvin’s DeKruyter Chair in Faith and Communication. He listed the church and clinical psychology as two examples of these mainstream institutions to which people would traditionally turn with secrets. “Maybe people feel like they don’t have a space to go.”

Calvin students have access to Unmasked, an application that provides an anonymous mental health support community, via their Calvin email accounts. Both Unmasked and social media accounts like Calvin Confessions keep posters’ identities secret, but the similarities end there. Posts on Unmasked tend to focus on mental health struggles, most comments are supportive, and peer moderators patrol the forum for harmful content; meanwhile, posts on Calvin Confessions are sometimes sexually aggressive, and the page is largely unmoderated.

This particular account, which surfaced in Sept. 2022, branded itself Calvin Confessions 2.0, and its administrators take on the persona of “John Calvin yaasified.”

“We’re almost like John Calvin –– kind of the antithesis of John Calvin, where he’s just super flamboyant and here for the girls and the gays,” Calvin Confessions said. Their goal is to “create some sort of online interaction between Calvin students.”

“Obviously, it’s probably not the best to spread rumors with your friends, but it’s comfortable to do it online,” said Calvin Confessions. “It just makes it more fun –– no consequences, really.”

Occasionally, the account will function as a quasi-news source. For example, when a Calvin University sign was vandalized in a protest against anti-Semitic comments made by a student organization, Calvin Confessions quickly posted a photo of the event. But its creators told Chimes that they don’t think of themselves in that way: Calvin Confessions is primarily about “individual and personal confessions,” not breaking news.

The account’s appeal, according to its creators, lies in its humor and how “juicy” the secrets are. “I think everyone loves to hear weird things that happen to other people,” they said. “People [at Calvin] come from sheltered areas. To see other students go through this random stuff is like: ‘Wow, this has really been going on behind closed doors, and I never knew that!’”

The shock factor of many confessions is fostered by the anonymity, Calvin Confessions told Chimes. “There’s some crazy ones that people would definitely not say if their name was shown,” they said. “Anonymous ones are usually more juicy and more fake.”

“Shock, anger, outrage, hilarity –– those are really unifying emotions,” said Mattson. But “they’re, unfortunately, only briefly unifying. It fades fast, and it doesn’t allow for that richness of neighbor[ly] love. If you tried to build a friendship on shock, you can see how little that would sustain the actual everyday work of being a friend.”

Discernment

The creators of Calvin Confessions do not automatically post every confession they receive, but sometimes discerning what to post can be tricky. “There was this one person who lived in [a specific Calvin dorm], and [the confession] described her room and said her name,” they said. The confession’s subject was “not really comfortable” with that level of detail being public, so Calvin Confessions ended up deleting the post.

The administrators attempt to distinguish between confessions that are “complimentary” to their subjects and “intense sexualization.” “There’s a line between funny and inappropriate,” they said. “We try to find that.” Humorous compliments, they told Chimes, are often well-received by their subjects.

They are also well aware that not everything they receive is true. “Sometimes, there are things like, ‘This is probably fake, but it’s funny,’” they said. “I guess it’s not that serious if we post something that’s fake.” In other words, they’re happy to post confessions that seem lighthearted and mainly humorous, but they try to avoid posting confessions with more serious allegations –– like, for instance, tales of students having inappropriate relationships with professors.

“We don’t want to spread misinformation about Calvin,” Calvin Confessions said. “We don’t want Calvin to get a bad reputation for this, whether it’s true or not.”

Indeed, according to Mattson, it seems likely that some anonymous confessions are not concerned with truth at all. Instead, Mattson said, they might better fall under the category of communication that philosopher Harry Frankfurt termed “bullshit.” “It’s not necessarily that it’s true or false but that it is completely disconnected from accountability,” Mattson said. “It’s not concerned about whether it’s true or false. It actually might be true, it might be false, but the person saying it really doesn’t care.”

Calvin Confessions told Chimes that users do not typically approach the account as a source of truth. “I’ve had people say to me, ‘A lot of this is probably not real.’ But they still enjoy it!”

“I think most of it is just made up to get attention,” said senior Sam Datema, who occasionally peruses the account. “I think I take comfort in believing it’s not real.”

In Oct. 2022, Datema discovered that he had been name-dropped –– first and last –– in a Calvin Confessions post. “I think Sam Datema might be homeless,” the post read. “I always see that b—- in the library.”

There had been similar jokes in Datema’s friend group, so Datema assumed it had been submitted by a friend. “I thought I knew who wrote it, but I searched my friend circle and I could not find anyone who wrote it,” he said. “To this day, I have no idea who wrote that. It’s a little strange.”

Datema was most surprised by how “relatively tame” the post was. “The rest of that account is just, like, foul,” he said. “Mine really wasn’t that bad. That’s what I was surprised by.”

Datema said that he had not been consulted before being publicly named, but given its tame nature, he wasn’t upset about it. “I really don’t care, but I know that some people probably would,” he said. “I’m easygoing.”

Mattson suggested that a “consent ethic” is a bare minimum, which ought to be replaced with neighborly love. “I think we need something more than a consent ethic,” he said. “A consent ethic doesn’t really seek the good of the other person. So, yes, I think it’s a bad idea to share somebody’s info without their consent. But in [a] Christian learning community like this, that’s not enough. [A consent ethic alone] is not seeking the good of the other person; it’s not seeking the good of the community.”

Calvin Confessions told Chimes that their policy on name-dropping depends on the confession’s intentions. “Usually, we’ll just post it. We’re not here to be the ‘what’s okay’ police,” they said. But “if it could be harmful or hurtful to someone, we wouldn’t post it.”

The creators draw a line between confessions and bullying, which is “intentionally to harm someone else.” “We try not to post those,” they said. “We don’t want to encourage bullying. Our primary goal is to keep it lighthearted.”

But Mattson warned of a darker side to social media, which often goes unnoticed: that the system itself encourages and profits from outrage. “We often treat our social media [apps] as if they’re playgrounds,” he said. “I would just really encourage people to recognize that social media are more like farms, and you’re the crop. You’re being harvested –– your attention is being harvested.”

Ultimately, then, his advice to Calvin students is to be attentive when they engage with social media. “Watch what it does to yourself, what it does to other people,” Mattson said. “Pay attention and act accordingly to what you notice.”