Student evangelism takes the gospel downtown

Grand Commission shares the gospel with the homeless in downtown Grand Rapids.

It’s freezing at the Rapid Central Station. A group of students stand in a circle almost shoulder to shoulder, shielding themselves from the cold. Though they are enjoying each other’s company, every once in a while someone’s head peaks out of the group and looks around the station. Sophomore Giulianna Giordano and first-year student Steve Koopmans spy a man sitting on a bench alone, smoking a cigarette. They pause, look at each other and make their way over to him.

Grand Commission – Grand Rapids, MI

Giordano and Koopmans are members of the Grand Commission, a group of students who evangelize on alternating Fridays in downtown Grand Rapids, focusing their outreach on the homeless community. John Standinger, a junior, began the organization in the fall of 2021.

While not yet a chartered student organization, Standinger said Campus Ministries has provided the Grand Commission with “all the support we need,” including the use of their table at the Cokes and Clubs gathering last spring. Despite changes in leadership over the past year, Standinger said, “God has really provided not only quantity … but quality.” The Grand Commission has seen its ranks grow to more than 17 members since spring 2021.

Standinger’s desire to evangelize began with an internship at Next Step Ministries, a non-profit focused on community service and relationship building. Standinger said he had several conversations about his faith with a student he served, and those conversations eventually led the student to accept Christ as his savior. The student spoke later to Standinger, attributing the conversations they had as a major cause in his change of faith. Standinger said, “I don’t take credit for him coming to Christ because that’s all God’s work, but it is so cool to be used as a tool.”

The Grand Commission is shaped by that same desire to build relationships. Standinger said, “It’s set up to create those opportunities … we want to develop a relationship with people. When you see a life changed, the great joy of that is just beyond comparison.” That doesn’t stop Standinger from the fear of that process. “There can be huge fear. I don’t want to drive [people] away from Christ or drive them away from me.”

Jim Elliot Fellowship – Chicago, IL

Jeremy Chong, a senior at Wheaton College, former leader of the Chicago Evangelism Team and founder of Jim Elliot Fellowship, felt that same fear. After becoming a Christian in his freshman year of high school, he felt a pressure to talk to his friends about his faith. He said he started by talking with cab drivers, but he felt a call to “go to the streets.” Although he was afraid, Chong followed the call.

Chong believes in an up-front style of evangelizing. “I don’t like to play games with people. I want to be very honest about why I want to talk to people, that I want them to be saved.” He describes an approach he calls “seeker sensitive,” which he says seeks to evangelize in a soft, cautionary way, using “bait and switch” tactics. Chong does not utilize a “seeker sensitive” approach. He says he wants to center every conversation around the narrative of the Gospel, described as “the extent of sin, the method of recourse, and the expression of gratitude.”

After his senior year of high school, in his hometown of New York City, Chong stood up in Times Square and delivered a sermon to the tourists, office workers and garbage collectors. “There was a huge crowd of people sitting there in Times Square, and maybe 20 or 30 people listened to the entire message respectfully.” He said he was overwhelmed by the effect he was able to have. “I reached more people in 10 minutes than some churches reach in an entire year.”

When Chong entered Wheaton College the next year, he immediately joined the Chicago Evangelism Team, a group of Wheaton students that commuted to Chicago every weekend to converse about and preach the gospel. He still discussed the gospel with people but now about half the time Chong was “open air preaching.” He compared both methods –– street evangelism and open-air preaching –– using a fishing metaphor. As the metaphor goes, one-on-one conversations are like using a hook, while preaching is like using a net. However, both types of evangelism led to a split between the CET and Wheaton College’s administration.

At the same time that John Standinger began forming the Grand Commission at Calvin, the members of the CET were dismissed from Wheaton’s Office of Christian Outreach. Wheaton’s administration cited the CET’s use of such words as “hell” and “damned” as evidence of “needlessly abrasive” evangelism tactics. The OCO has been restructured into Ministry and Evangelism, but is led by the same individual, Jared Falkanger. While the director of the OCO, Falkanger was responsible for the CET’s dismissal. To the Wheaton Record he stated “a conversation between two people about faith … without these terms can be evangelistic.” Chong responded to this statement, saying “A love that is detached from the truth is actually not love — it’s niceness.”

John Standinger is aware of the aversion that exists towards words commonly used in evangelism. But he sees them as necessary. When asked about the importance of the gospel to the Grand Commission, he said “The gospel is a very necessary [message] but also can be very offensive because it says, ‘You’re a sinner.’”

Chong was in his second year as leader of the CET when the group was dismissed. Within a few weeks, Chong created the Jim Elliot Fellowship, staffed by the same seven students who made up the cabinet of the CET. Two years later, JEF still goes to Chicago every weekend to engage people with the gospel.

This wasn’t JEF staff’s first brush with high level conflict either. In 2019, the students who now lead JEF filed a lawsuit against the city of Chicago for infringing their first amendment right to speak in a public place about their faith. Security guards, police officers and city ordinances were slowly making it more and more difficult to preach in Millennium Park, Chicago’s best-known public park with its large, metal, bean-shaped statue. Lawyers from the Alliance Defending Freedom were eager to take their case, and worked pro-bono. The case was taken to a federal court, where Judge John Robert Blakey ruled it was within their rights to preach in the park.

Chong said that the call that he felt initially has not waned, and that truthful preaching of the gospel is something he is very concerned about. No matter the discomfort he might create, he said the gospel is more important. When he approaches someone on the street, he told Chimes, “My philosophy … I can’t convert you, but I want to be in heaven with you.”

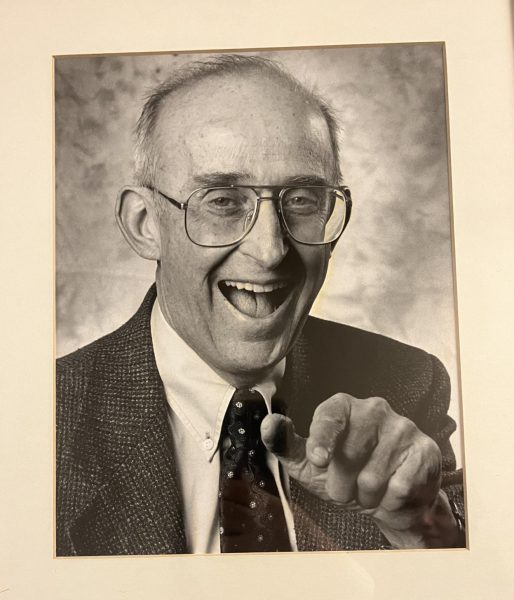

Dr. Noel Snyder on street evangelism and the Church

According to the Rev. Dr. Noel Snyder, an ordained minister in the CRC and a professor within the Congregational Ministry Studies department at Calvin University, said there are many places street evangelism can go wrong. He said it can make someone feel dehumanized, just a “notch in a belt.” The worst kind of evangelism, Snyder said, makes the gospel into “something that is being sold, and we’re all being sold so much all the time.”

Snyder told Chimes he believes evangelism has an important part to play in the Church, and that the sharing of the gospel is “essential [to] what the Christian faith is about.” When churches think of growing their membership today, most new congregants are coming from other churches, according to Snyder. Not new believers, but new congregants. “Many churches had gotten so used to institutional maintenance, that they really wouldn’t know what to do if someone new to the gospel walked in the door,” he said. Done in the right way, Snyder believes evangelization is an essential and needed part of the Christian Church. “In the US, a lot of us Christians could use a challenge to step out a little bit more.”

The Grand Commission doesn’t foresee any lawsuits or a falling out with Calvin’s administration, Standinger says. They haven’t converted crowds of people, nor have they significantly contributed to the congregations of any church. They’ve been downtown once this semester, the fourth trip the Grand Commission has taken since beginning. Despite all this, one idea permeated the atmosphere last Friday; everybody remarked on the significance of the experience, and how meaningful the conversations felt.

On this trip, Giulianna Giordano and Steve Koopmans find someone to pray for. They approach the man sitting alone on the bench and stand in front of him, arms clasped awkwardly in front of their bodies. They greet him, exchange names, and ask him where he’s coming from. He works in a machine shop downtown. Next comes the hard question. “Is there anything we can pray for you about?” He promptly says yes. Giordano’s and Steve’s hearts leap. They come closer and sit down in front of him. His cousin has had a heart attack. They pray, asking for healing. After the prayer, conversation continues. The machinist is on his way to an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, he’s 8 months clean, they congratulate him. Things continue amicably until the man’s bus arrives. He walks toward the stop, but before he gets on, he turns and blesses the students.