Tracking the trash: It doesn’t just go to a landfill

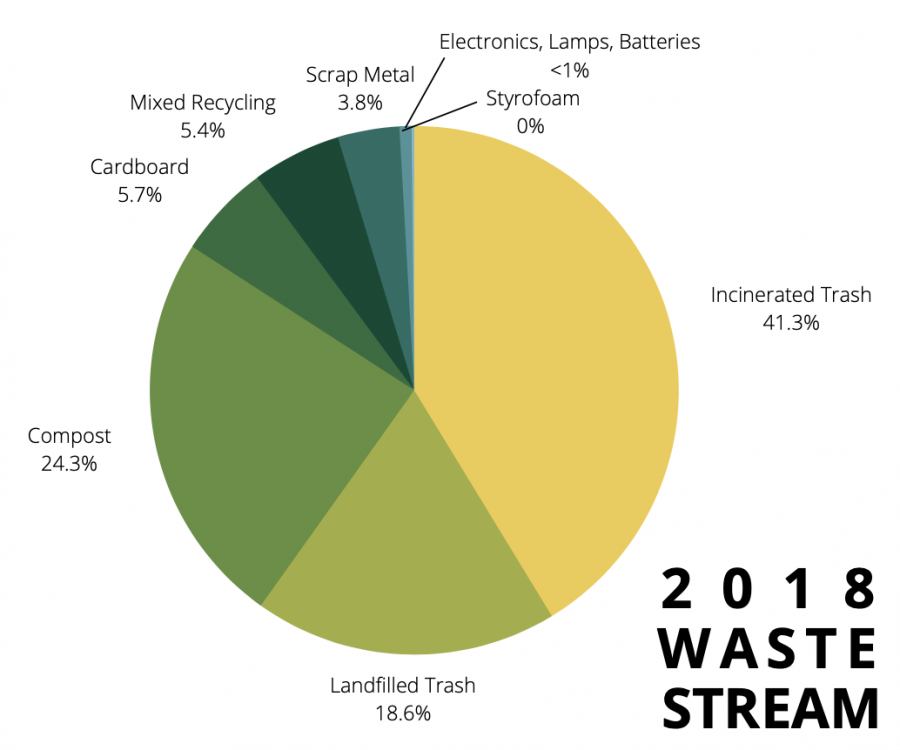

Calvin’s waste covers many different categories.

Next time you throw away your styrofoam meal box from the dining hall, take a moment to think where it will end up.

According to Henry Kingma, Recycling Coordinator, Calvin produced over 1,160 tons of waste in 2020. The process of how Calvin’s teams manage to dispose of waste, however, depends on where the waste is headed.

“In normal times, we have a number of places that accept our waste,” Kingma said.

Trash that students throw into waste baskets in the dining halls, dorms, academic buildings and KE apartments lands in the dumpsters parked outside the academic buildings and dorms. Front-end loaders collect and empty the dumpsters weekly. Garbage trucks managed by Arrowaste Corp. then remove the garbage and take it to the Waste-for-Energy Facility in downtown Grand Rapids, where it is incinerated.

“A lot of people don’t know that we incinerate the bulk of our waste,” Kingma said.

Once waste arrives at the Waste-for-Energy facility, trucks dump trash onto a giant cement floor. A mechanical loader pushes the trash into a pit and smushes the trash into a compacted ball. Once it has been compacted, a crane-claw system transfers the compacted waste into one of three incinerators. Non-combustible material is then emptied from the incinerator and sent to a landfill.

“It’s 90% of the volume of the original trash,” Kingma said, “so only 10% of the volume ends up in the landfill.”

The heat from the incinerators generates steam, which then turns giant turbines that generate power for downtown Grand Rapids.

“It’s quite a place,” Kingma said.

According to the Kent County Department of Public Works, the facility generated 96,000 kilowatts of electricity in 2018. That provides enough energy daily for 11,000 homes.

Not all of Calvin’s waste heads to the incinerator, however. Bulky items, such as construction debris from building renovations, as well as the trash collected from move-in and move-out days, won’t fit into the incinerator. The facilities department sends this trash to one of the two landfills in Kent County.

Once trash arrives at a landfill, machines organize and compact trash so it can begin the decomposition process. Because of the toxic components of products that end up in landfills, such as microplastics from dish soap or anti-flammable hydrocarbons from rain coats, landfills release gases into the atmosphere.

Landfills are only semi-isolated from the surrounding environment. Whenever it rains or snows, the water that seeps into the landfill picks up contaminants. The resulting liquid, which landfills collect in retention ponds adjacent to the landfill, is called leachate.

There are two main ways to dispose of leachate: send it to a water treatment plant or send it underground.

Landfills that opt to treat the leachate truck it to a treatment plant. Unfortunately, water treatment plants are unable to remove many significant contaminants. Some poisonous materials, such as PFAS, toxic compounds found in water-resistant coatings and plastics, are present in high concentrations in landfill leachate. When the water treatment plant releases water back into the environment, landfill contaminants enter it, too.

Landfill leachate can also be injected into high-pressure disposal wells. Leachate wells are drilled into shale rock at 4,000 feet below the surface. Unfortunately, these wells can malfunction and permanently contaminate vital groundwater and surface water, because leachate isn’t cleaned before it is injected into the wells. According to the Michigan Department of Environment, there are over 1,250 leachate wells in Michigan, and landfills in Kent County’s leachate send some of their leachate to wells in Ottawa County.

Not all waste is fit for an incinerator or a landfill. Before COVID-19 temporarily suspended Calvin’s recycling program, co-mingled recycling–recycling that isn’t sorted by material type–went to the Kent County Recovery Facility and Education Center. During the pandemic, this waste has gone to the incinerator.

The facilities department recycles scrap metal and corrugated cardboard (the two-layered cardboard used in packaging) by sending it to PADNOS, a West Michigan-based recycling agency, according to Kingsma.

Calvin sends universal waste–waste that contains hazardous materials but is very common, such as electronics and lightbulbs–to various electronics recycling centers. Expired electronic devices, like outdated or broken computers and batteries, go to Valley City Electrical Recycling; fluorescent lamps are sent to SET Environmental.

Electronics recycling usually involves disassembling devices, separating and categorizing hazardous materials, cleaning and then ultimately shredding them, according to Kingsma.

In a typical year, Calvin recycles about 700 pounds of batteries and 1.42 tons of lamps.

During pre-COVID times, Calvin also disposed of composted waste, including food waste from the dining halls, by sending it to a commercial composting facility. This waste currently goes to the incinerator.

These operational changes present particular challenges for both the Facilities’ and dining services departments.

“Dining services wants to do the right thing and use compostable products, and it’s good to support that industry,” Kingma said. “But you don’t get the end result benefit of compostable material going into a landfill when you’re incinerating it.”

According to Melissa Smith, dining services manager, disposable trash from the dining halls has increased as a result of COVID. In order to decrease disposable trash, dining services has implemented reusable Green2Go containers.

“Green2Go containers will significantly decrease the amount of disposable containers we use,” Smith said.

Although packing waste has increased from the pandemic, overall food waste has decreased as a result of making dining services safe for COVID, according to Smith.

“We have not been able to have every station open like we would for a normal school year so we have adjusted our production,” Smith said.

The Facilities department has continued to recycle hazardous universal waste throughout the pandemic.

“We’re required to do it by law,” Kingma said, “but we would do it anyway, because of the hazardous materials in those products.”

As a whole, Calvin produces over 1,160 tons of trash in a non-COVID year. About 460 tons of trash ends up in the incinerator and 200 tons in landfills.

During the pandemic, Calvin has collected much less trash. According to Kingma, the reduction in waste production is likely due to the campus-wide shutdown during the spring and summer of 2020. Despite the decreases, however, Kingma emphasized the importance of continued vigilance in waste education.

“Not a lot of people know what happens,” Kingma said. “A lot of people dispose of their waste and don’t give it another thought. It doesn’t just go to a landfill.”

Kingma’s name has been corrected. Chimes regrets the error.