Abuses of religious power: Why do they happen and what can we do about it?

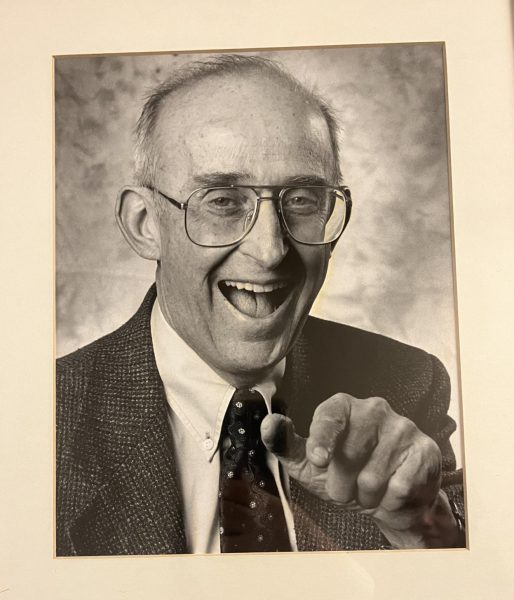

Ravi Zacharias. Carl Lentz. Bill Hybels. Nearly every week, new stories break of how powerful church leaders have abused their power and their congregants. Chimes sat down with social work professor Rachel Venema and history professor Kristin Du Mez to talk about what structures result in abuse and how the church can prevent further misconduct from taking place.

Chimes: Can you tell me a bit more about your focus in your field of study?

Venema: “Most of my research is on institutional response to sexual violence. I started with my dissertation research and I worked with the police department and looked at how they perceive and respond to reported sexual assaults. I’ve also done some work at Calvin doing a sexual violence climate survey… we [only] had anecdotal evidence [about sexual violence on campus]…but we didn’t have any data on it… so I’ve done two studies on campus looking at the campus climate, looking the environment, acceptable talk, barriers to reporting, and how many students do experience sexual assault during their time at calvin. I’ve also done one other related study about illicit massage businesses…knowing that it is very likely that many of the workers may be victims of trafficking.”

Du Mez: “I’m a historian of gender, religion, and politics. I’ve written on the history of Christian feminsim, the history of anti trafficking activism, sexual abuse particularly within Chiristian communitiies, and my most recent work is a study of white evangelical masculinity and militarism and connections between patriarchial teachings and cultures of abuse.”

Chimes: What power structures specific to churches do you think are causing this environment of sexual assault and silencing of the victim?

Du Mez: “To me what’s most intriguing is the cultures and systems that allow this abuse to take place and that resist any exposure to this abuse, that give cover to abusers. These are good people, good Christians who are not themselves perpetrators, but they end up being complicit in allowing this abuse to continue. Some of the things that I see in that area are a real emphasis being placed on the authority of the leader…the obligation of Christians to submit to their “God-appointed authority” is the teaching that’s really pervasive in these circles…Communities have also been designed, in many cases, with little accountability. The board of directors are often family members or close friends and so there really isn’t accountability built in, and there’s also oftentimes a lot of money at stake. These ministries are, themselves, these massive businesses…if the leader at the top goes down, the whole business is going to fail. So there are often financial incentives here, and there’s also that spiritual element of people who are convinced that whatever organization they are part of is doing the Lord’s work. Any kind of bad press that comes to the situation will be tarnishing the witness of the ministry and the church. There is a lot of incentive, then, to cover it up to stay quiet. These patterns are very common. People in power will also use the language of unity of the church to quiet any dissent…and they’ll use Biblical verses about gossip to prevent the exposure of any abuse.”

Venema: “I think the role of pastor is elevated too high…there needs to be a team of people leading and more egalitarian leadership. The pastor or pastors get elevated to this really unhealthy, god-level figure; they are in charge of everything and that is not how it should be, in my opinion. It should be a group…In my church, which is CRC, there is a group of elders. The pastor is one of the elders… that is their role but they are not in charge. There has to be power spread over a group of people that can hold the pastor and other leaders accountable as well.”

Chimes: Do you think that the reluctance to put women in leadership positions in the church has had an effect on this environment?

Venema: “I think that is a major issue, the fact that there aren’t women at the table in all of these spaces equal to men. Women have unique experiences related to harassment and all sorts of sexual misconduct, that’s just the reality. Women often see it differently. Women will often see themselves as a potential victim whereas men will see themselves as a potential accused. It’s probably a natural, psychological response for men to protect someone they can identify with. I think if women were at the table, churches would respond very differently to sexual abuse, to domestic violence, to all sorts of things.”

Chimes: What could be done to restructure religious institutions in a way that would make sexual assault by authority figures less common or improve the environment for victims to speak out?

Venema: “A good place to start is increasing awareness among everybody about what sexual assault is…because I think the myths related to sexual violence are still pervasive and they’re just not true…[There needs to be] more open communication about the issue and somehow building in nuance that the person in charge can also do bad things. There needs to be a variety of outlets where you could go and talk to a parent or a friend or safe adults. As for institutions, I think that building in policies and processes to deal with things when they come up, not if they come up [is important]. They [should] know exactly how to get in touch with the police and who to talk to and what to do.”

Chimes: Do you think these trainings and awareness affect potential predators as well or just help the response to sexual violence?

Venema: “We know a lot less about how to prevent it. I do think it starts really young… in terms of having autonomy over your body, [we should be] teaching that to kids very young. I think there needs to be more intentional work with boys because…they’re socialized that way. I think a lot of what we see is a result of poor socialization…boys are still taught this sort of conquest/conquer thing… I don’t think awareness raising and training of adults is going to prevent perpetration because often people who are perpetrators are repeat perpetrators.”

Du Mez: “It would require almost a complete dismantling of many of the [structures] because so many of these organizations have really grown up around one charismatic individual, so it’s the success of that individual that really determines the success of the organization. People join the organization both because of the charismatic leader of the individual and because they deeply believe in the mission of the organization but then the two become really inseparable. I could give pointers that the board has to provide true accountability, but every board will suggest that that’s exactly what they do when they don’t.

The deeper problem here is the money that’s tied to these ministries…people want to focus on the ministry and and convince themselves that that’s the only motivation here, and that expansion and the power of the leader is really just a means to an end–and that end is always something beautiful and good. We just need a lot more rigorous honesty in Christian institutions and organizations, that we are not just altruistic organizations; we are not just bringing the gospel.

We are also looking after our own interests…religious organizations tend to have a much more difficult time acknowledging the various motivations that are at play…Many of the boards that are currently in place, many Christian organizations are not equipped to offer that kind of rigorous scrutiny of their own motives…Then I guess even more education for how these things work: be very hesitant to use language like unity, and be wary of your own instincts to protect your organization. Those can so easily be used to defend toxic cultures that language can be so again we need to be very self-critical.”

Chimes: A lot of what you’re talking about is very applicable to mega churches and those with a lot of money. Is there less of a danger for smaller churches?

Du Mez: “No. Not at all… It happens in large churches and in smaller churches because the size of the structure doesn’t really dictate the power imbalance at all. In many cases there is even less accountability there because there are not many people keeping an eye on it. Size doesn’t really seem to be a factor in propensity for abuse.”

Chimes: What is the appropriate response of a church if an authority figure is accused of sexual assault?

Venema: “The police…is not a perfect response…but it is a good first step. It really depends on the evidence that you have…you don’t want to hurt someone’s reputation if they are innocent, but you also don’t want to protect them at the risk of harming others. I think it completely depends on the case and the situation but I do think there needs to be several people involved…a group of people that has been trained on how to respond… what to ask, what not to ask, how to make a report to the police and that team of people can figure out how to respond. You get into a lot of trouble when you just have one or two people who inevitably will be in relationship with the person in authority… they cannot conceive that the person would do anything like that so you have all these biases. You need to also have an external person involved as well.”

Chimes: What can we as members of a church and Christians not in authority positions do to help victims of sexual assault?

Venema: “Building a culture where it is okay to talk about these issues is really important. I think it can have an effect on the willingness to come forward and report, but also on the healing process becase… sexual assault survivors experience this sense of shame and feeling alone… this weight they have to carry. The reality is that so many people have experienced that. To provide a space where it’s acknowledged and you have a process to hold people accountable but you also have a space to heal [is important].”

Du Mez: “Be very, very hesitant even before any allegations are made about the power you place in the hands of any individual…I think the most important things that we do come long before a crisis situation…we really need to think about how we prop up each others’ authority. If there are allegations, do not try to tamp those down. Do not let your friendship or your investment in the mission allow you to participate in the silencing of potential victims or alleged victims, which is the impulse that many people have. Do not let your experience with the accused lead you to disbelieve allegations. This is not saying that all allegations are true, so the best thing to do is to immediately turn anything over to proper investigators and let them sort it out. So many Christian organizations want to deal with this internally, and human nature is to say well he’s never said anything to me, which is how abusers work. They don’t abuse every single person who comes across their path, so rather than seeing that as evidence [against the victim] we should use that to better understand how abusers act.”