President Le Roy turns down pay increases while receiving total compensation at peer median

President Michael K. Le Roy has made efforts to limit the compensation he receives, despite a strategic plan goal that puts his earnings at a competitive median to those in his position at similar institutions.

In three of the six years Le Roy was eligible for an increase in pay (base salary), he did not take the increase.

“President Le Roy has consistently asked the board not to provide him with a salary increase if the rest of the staff does not receive one,” stated Craig Lubben, chair of the Board of Trustees (BOT), the committee that sets the compensation the president receives.

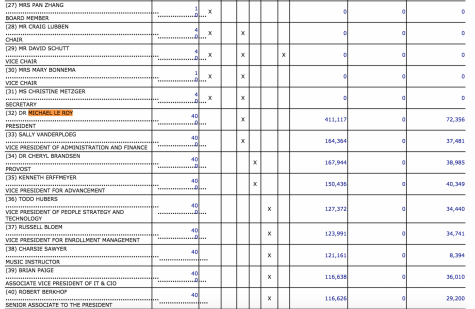

A snapshot of Calvin’s IRS Form 990 in fiscal year 2015–16, highlighting the compensation President Le Roy received.

The rising numbers of Le Roy’s compensation over the years, as seen in Form 990s from previous years, reflects a fluctuation in the benefits he received, which are the same benefits offered to faculty, such as tuition for dependents, mileage, life insurance and retirement funds. In 2017, for example, there were more of Le Roy’s dependents receiving these benefits than in 2014.

A major portion of Le Roy’s benefits goes toward college tuition for dependents. All Calvin faculty receive this education benefit for their dependents, which entailed an 80 percent tuition waiver for college education. As of this September, this waiver increased to 100 percent, but Le Roy has requested that the benefit for his dependents remain at 80 percent. This benefit usually applies to attendance at Calvin, but like some other dependents of faculty and staff, Le Roy’s dependents participate in a Tuition Waiver Exchange program for members of the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU).

Le Roy has made other adjustments to limit his compensation as well, such as changing the college contribution to his retirement plan to match the recent changes for faculty and staff. The contribution recently changed from 10 percent of the salary to 6 percent, with an opportunity to be matched another 2 percent if an employee contributes 2 percent more from their salary.

Le Roy has also requested that the BOT rescind a planned pay increase for him due this year.

“As salary increases have been constrained for faculty and staff, President Le Roy believes that his compensation should be similarly constrained,” wrote Andy George, director of human resources, in his notes to Chimes.

Just as faculty and staff did not receive pay increases this year due to budgeting, the money Le Roy would have received is not actually present. Instead, his constraint helps the college in reducing overall expenses and therefore work towards maintaining budget-neutral status.

“I think he’s paid fairly, given the responsibility of the position, the fact that it is in line with the college’s compensation philosophy and that it has been verified by an independent third party as being reasonable under IRS guidelines,” said George, who noted that top executives at big for-profit corporations make considerably more than college presidents.

“Compensation is based on education, skills, experience, what decision-making responsibilities you have … and that’s not unique to higher education,” George explained.

The Calvin College president received a total compensation of nearly half a million dollars in fiscal year 2015–16, according to Calvin’s Form 990 to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The document, which is publicly available online, reports that $411,117 goes to the president in a category labeled “reportable compensation from the organization.” A further $72,356 is applied to “estimated amount of other compensation from the organization and related organizations.” Together, these numbers total $483,473.

However, both of these numbers include various benefits and do not merely reflect his base salary. According to George, the president’s base salary is closer to $300,000, although the exact amount is not specifically identified because the IRS does not require that the number be reported separately from the benefits.

The base salary is influenced by the compensation philosophy outlined in the college’s 2019 strategic plan, which was put together with the input of faculty, staff and administrators.

Section III 4 C of the 2019 strategic plan states, “The median salary of faculty, staff and administrator groups will exceed the median salaries paid in similar categories by peer institutions.”

The BOT sets the president’s pay in accordance with the compensation philosophy, Intermediate Sanctions guidelines set by the IRS, regular review of the compensation program as explored by the BOT Executive Compensation sub-committee, and recommendations from Sibson, a consulting group with expertise on higher-education executive compensation. Calvin’s human resources department hired Sibson, an independent third party, to review president pay in 2014 and 2018 for competitiveness and reasonableness under the IRS guidelines.

To make their assessment of how the president’s pay compared to that of other college presidents, Sibson collected pay data from Calvin, data from published Form 990s from a list of 30 similar peer institutions (a list Calvin uses for analyzing other areas as well, such as enrollment) and external market data from the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources (CUPA-HR) and CompAnalyst surveys. The findings of their analysis and recommendations were then presented to the BOT Executive Compensation sub-committee.

Sibson found that in 2014, Le Roy’s base salary was 94 percent of the peer median. In following with the compensation philosophy, his base salary reached 100 percent of the peer median in 2018. Similarly, his total compensation (that is, including benefits) was at 95 percent of the peer median in 2014 and 111 percent in 2018.

Le Roy is not the only college employee to reach the median pay. With recent pay increases for full professors, all faculty are now paid at or even above their market median, and so are two-thirds of staff, with the remaining one-third to move from 95 percent to 100 percent with the next pay adjustment from the college.

In comparison to the United States president, whose salary is a comparable $400,000 a year, George noted that those in the highest levels of national politics tended to be wealthy and were unlikely to be in it for the money, which would be meager for the amount of responsibility taken on in return.

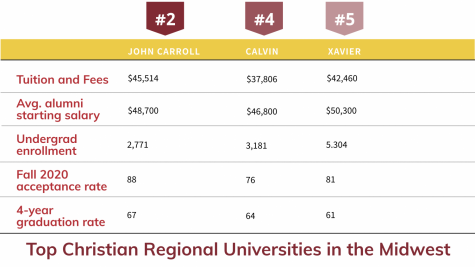

A closer comparison would be to look at the total compensation (which includes benefits) of college presidents at schools similar to Calvin, and at a similar time period to the fiscal year cited from Calvin’s 990 record, which was from July 1, 2015–June 30, 2016.

At Hope College in their 2015–16 fiscal year, their president at the time, John C. Knapp, received a total compensation of $401,194 (total compensation defined as counting the two aforementioned categories of compensation on form 990). At Cornerstone University around the same time, their president, Joseph Stowell, made a total $235,896. Meanwhile, the president of Davenport University, Richard Pappas, made $749,387 that year, and at Wheaton College in Illinois, $528,666 went to their president, Philip Ryker. At Spring Arbor University, their president, Brent Ellis, made $232,730, according to the form 990s filed by these institutions.

“Given the high level of leadership responsibilities and travel required, there are days when I wonder if the pay adequately fits the personal demands and toll placed on college presidents,” George added.

George challenges those who share a different philosophy (based on “whatever amounts to too much for a person to make”) to consider, “Well, what’s the right amount? What’s too much?”

While the answer to this, he says, would require “an intensive compensation study through a third party,” Dianne Cayetano, a senior, believes that it is worth the effort to investigate, come to a consensus and regularly re-evaluate such a decision of “what’s too much” for Calvin’s president in order to avoid excess expenditure and to make a statement to the world that Christians need not be reliant on their money.

“Even if your job is especially stressful, how is having more money going to help remove that stress?” Cayetano asks.

Although she concedes that the president can use a higher pay to spend on some luxuries that can make life easier, she asserts that there ought to be some ceiling for salaries, where anything above would be “too much.” While Cayetano does not offer a number, she is skeptical that the expenses for Calvin’s president to live a relatively comfortable life matches the median pay decided by the aforementioned processes.

Cayetano also suggests that, as a Christian institution, Calvin’s salary offerings should not be solely based on the trends of the world. She is concerned that brushing aside the idea that there might be an amount that is “too much for a person to make” could lead to a love of money that the Bible warns against.

Le Roy declined to comment on the matter of how his Christian faith plays into his personal expenses and charitable giving, considering it to be a private matter between him and his wife.

However, one consideration for the compensation philosophy that Calvin follows in its strategic plan is the necessity of attracting qualified candidates.

“If you do not pay close enough to the median, you will be unable to fill that job,” said George.

Natsun Eisen '14 • Nov 18, 2018 at 8:58 pm

I respect President Le Roy’s efforts to avoid bad press by receiving pay increases when Calvin’s faculty receive none, but this doesn’t answer a fundamental question I believe all Christians should be asking:

Why should a Christian institution be paying anyone more income that a very reasonable number that ensures an acceptable level of worldly comfort? Obviously, the economic argument is that you need to pay market level salaries to attract the necessary level of talent for certain positions.

However, if Christians’ first priority is to serve God to the best of their abilities, then why would Calvin struggle to find an individual capable of leading a large organization like Calvin if the job paid a very comfortable 150,000K per year?

The lack of reasonable answers to questions like these undermines all the lip service to Christian ideals.