Talk encourages “being the guest” in Islamic contexts and beyond

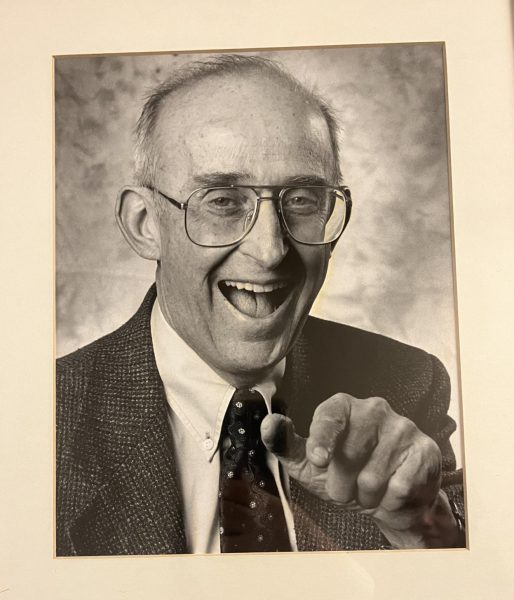

Rev. Justin Meyers of Oman’s Al-Amana Centre reflected on his experiences of Islamic hospitality on Monday evening, sharing stories and observations with about 35 attendees in the Commons Annex Lecture Hall.

After a dinner catered by Le Kabob, interfaith intern Manato Jansen introduced Meyers to the event’s attendees. Meyers grew up in Grand Rapids and studied at Western Seminary, after which he served Reformed Church in America (RCA) congregations in upstate New York and New York City. In 2013, he received an offer to join the Al-Amana Centre, and Meyers, his wife Stephanie, and their two sons moved to Oman.

Officially called “the Sultanate of Oman,” the country is about the size of Colorado and is home to almost 4 million people, 6 to 8 percent of whom identify as Christians. Although Oman is a Muslim-majority nation like many of its neighbors, the majority of its people are Ibadi Muslims, unlike any other country in the world. The Shia and Sunni traditions dominate most other regions. Meyers described the country’s religious groups as living in peace but that violent groups often use faith as an excuse for their political goals.

“The tension is political, not theological,” he said.

Oman’s peaceful intra-Islamic relations, he said, pave the way for peaceful interfaith relations as well. The Al-Amana Centre, where Meyers works, takes its name from the Arabic term for “sacred trust,” as when God entrusts creation to humanity in the Garden of Eden. As the Centre works on “projects of peace and understanding” at the bequest of the Ministry of Endowments and Religious Affairs, trust must pervade the center’s every communication and action within its home nation.

Living in the country has allowed him to experience its generous expression of hospitality, which Meyers named as “part and parcel of Oman’s expression of Islam.” Hospitality manifests in the constant refrain of Oman, from friends and strangers alike: “Please, you must come in for coffee and dates!” According to Meyer, Omani hospitality is also a holistic concept, extending to providing for everyday needs as well.

Meyer stated that this task becomes complicated, however, when Western Christians encounter Oman’s anti-proselytization laws. While the country’s state religion is Ibadi Islam, it does not ban Christianity or even cross-religious conversion (the latter, Meyers said, is attributed to a failure to teach Islam correctly). When Western visitors have secretly distributed Christian tracts or otherwise attempt to convert Omanis, the perception of Christians as dishonest only grows.

“Handing out tracts and flying home often inhibits the witness of the Christians who live there every day,” he said.

Calvin alumna Lydia Cupery found this perspective “refreshing,” especially after years of hearing only about tract-style forms of witnessing.

“Maybe,” she said, “forming a relationship is better for everyone.”

Meyers suggested a different — but not new — approach to Christian mission. In Luke 10, Jesus sends out his disciples to go and be guests, bringing peace to each house as they travel.

“I want to think about Christian mission as being the guest,” Meyers said. “What if we trained our church members to go and be the guest? We might have a healthier version of Christian mission, both here and abroad.”

With a dose of humor, Meyers shared examples of how relationships have broken down stereotypes, both of Christians about Muslims and vice versa. Though Oman forbids proselytization, Meyer warned his listeners against conflating proselytization with evangelism. In Oman, Meyers has still been able to embody Christ and acknowledge him as Lord; he can still explain his devotion to others. False stereotypes can be replaced with real stories:

“Because I was a gracious guest, [my friend] was able to change his mind about Christianity.”

After his presentation, Meyers asked for questions from the event’s attendees. Topics ranged from the rise of secularism to differences between Islam and Christianity to worship at Christian churches in Oman.

A student asked what would prompt Christians in the West, particularly the United States, to approach Christian mission from the perspective of “becoming the guest.”

“Sadly, I think that the only way the church will change is if it falls out of power,” Meyers said, citing its Western dominance as a unhealthy source of arrogance.

Senior June Tsujimoto appreciated the talk’s implications for American Christians, especially on a postural level.

“How Christianity operates in the states needs to change,” she said. “There are better ways to do it.”

Calvin’s Service-Learning Center will continue to sponsor and host more interfaith events throughout the semester, including an Abrahamic dinner with Muslim, Christian and Jewish panelists at Temple Emanuel on April 17.

Senior June Tsujimoto • Apr 16, 2018 at 10:38 pm

Heyyyyy Courtney,

Nicely summarized! Good job on the article:)

Except you missed one thing; I graduated Calvin last May and I don’t attend Calvin anymore…

Anyhow, keep up the good work and hope to see you at other interfaith events!

Thanks!

June T