Calvin student Alison Chen first used the Michigan e-Library Catalog — better known as MeLCat — to request a book when she was 10. Her relatively small local library didn’t have the biography of a Holocaust survivor that she needed for a project. However, using MeLCat, Michigan’s interlibrary loan program, Chen was able to request the book from another library in the state that had a copy and have it delivered to her library.

Getting the book ended up being part of a “really cool experience” for Chen, who later met both the author and the person whose life the biography recounted.

Since then, Chen, a junior studying history and biochemistry, has used MeLCat’s interlibrary loan program many times to request books for class projects, research, and personal reading. “It’s mind-blowing to me that I can just ask somebody, another library, very nicely, to send me a book that they don’t have here, and they’ll be like, yeah, here’s the due date,” said Chen.

Now, after another round of cuts to federal agencies, MeLCat and interlibrary loan programs like it in other states have found themselves without essential funding.

Budget cuts

Last month, President Donald Trump signed an executive order ordering the Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS) — along with several other federal agencies — to reduce its operations to the “minimum presence and function required by law.” The IMLS, established by Congress in 1996, provides $211 million in funding to library services across the country through grants given to and managed by state governments.

These grants are then used to fund a variety of library services and programs, including interlibrary loan services like MeLCat, online resources, and summer reading programs. In Michigan, this includes access to EBSCO, a database of academic journals, as well as many e-books and a database of resources for small businesses, according to David Malone, dean of Calvin’s library.

“We want to provide services to our communities, and those services are information and resources, and a huge amount of this access to information and other resources is going to go away if this funding is not replaced,” said Carol Dawe, director of the Lakeland Library Cooperative, a network of 42 public libraries in West Michigan.

What is MeLCat?

Established in 2005, MeLCat allows Michigan residents to request materials through an online catalog from over 435 participating public and private libraries across the state. These materials are then shipped to the resident’s preferred library at no cost to the resident. In 2024, about a million books were shared through MeLCat, according to Dawe.

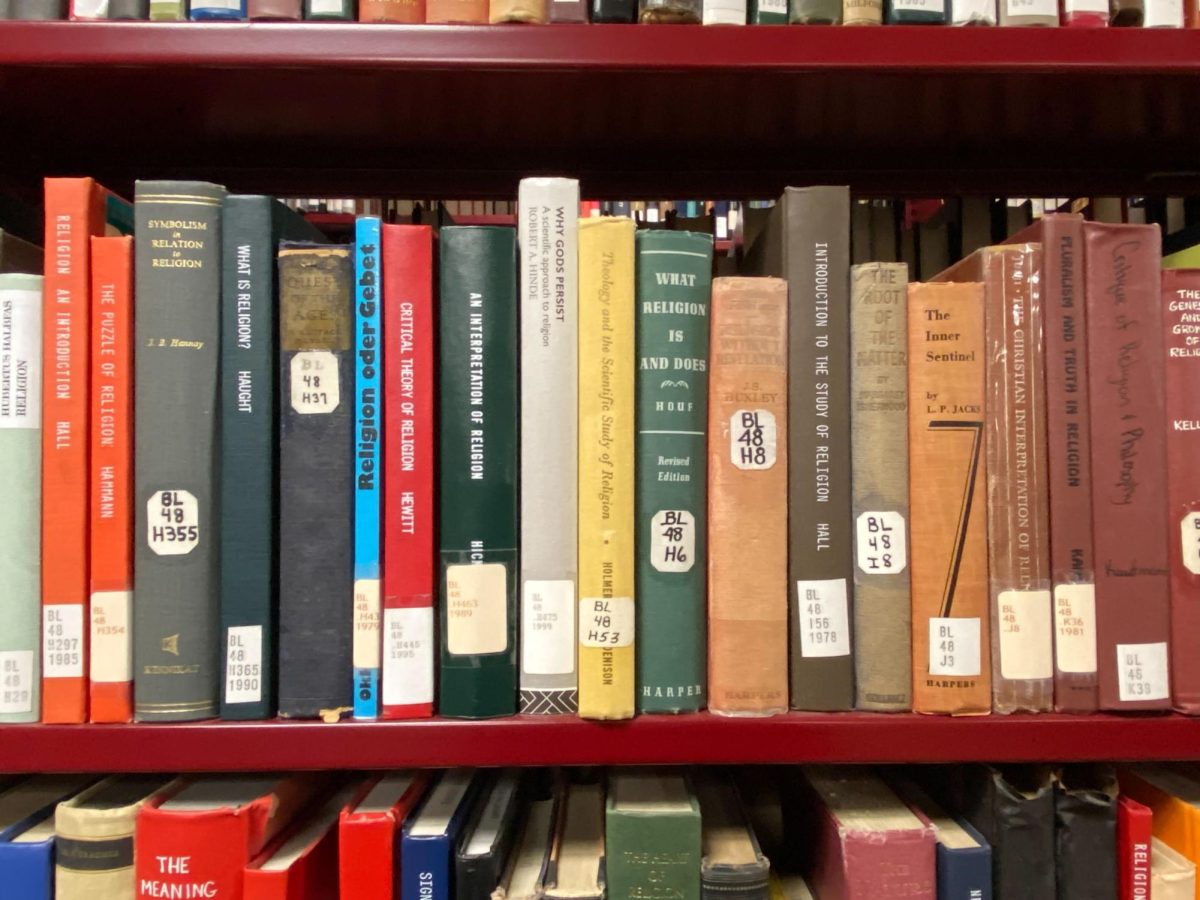

MeLCat and programs like it in other states allow libraries to focus on purchasing the materials they need the most. “Each library develops its area of specialty or just the collection it really wants to have and then borrows the others,” said Malone.

The ability to focus resources is especially important for smaller libraries and those with less funding. Malone noted that many school libraries rely “solely on Mel-Cat to provide their students and faculty with current scholarship.”

However, Dawe emphasized that even larger, better-funded libraries, such as those in Grand Rapids and East Grand Rapids, will be limited by the loss of MeLCat. “It’ll affect every library in the state of Michigan,” said Dawe.

This includes Hekman Library, which will have over 500,000 physical books and journals even after a planned downsize. Taylor Trenta, a senior studying history, said she has used MeLCat to borrow over 20 books in the past semester alone — many of them for her senior project. “If I didn’t have [MeLCat], I’d be missing out on half of the sources I need,” said Trenta. “We have books, but we don’t have enough to cover everything.”

History

Federal funding for individual libraries has existed since 1956 when Congress passed the Library Services Act, which budgeted $7.5 million annually for five years to improve public library service in rural areas; the funding was renewed in 1962.

In 1996, Congress passed the Museum and Library Services Act, which established the IMLS to coordinate federal research and funding related to museums and libraries. A subchapter of the act — called the Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA) also authorized grants to states that will allow them to improve and expand library services, and “encourage resource sharing” between libraries.

In Michigan and many other states, this funding supported the creation of electronic interlibrary loan systems such as MeLCat. These electronic programs replaced an older — and more time-consuming — method that required librarians to mail request forms to other libraries. “We have come such a long way to add value-added services for libraries that are cost-effective, efficient, and imperative for people to be able to get the information that they need,” said Dawe.

According to Dawe, “public libraries are predominantly funded through local sources such as millages [and] property taxes.” However, LSTA funding allows libraries to work on cooperative programs — such as interlibrary loan programs and online databases — that are “vital to the community,” said Dawe. They are also used to fund summer reading programs, the Department of Education told Chimes in an email.

What’s next?

Using the metaphor of program cuts at a university, Dawe emphasized that programs like MeLCat will be difficult to reinstate if they go away due to lack of funding. “Let’s just say somebody says, let’s just get rid of the foreign language department. Okay, so you fire all those people. Then someone says, ‘gee, maybe we shouldn’t have done that,’” said Dawe. “How do you rebuild a department back like that if everybody’s gone?”

Malone, who has worked in library services for over 30 years, said that this is the first time he’s seen library funding threatened to this extent in Michigan. However, at one point, the Consortium of Academic and Research Libraries in Illinois (CARLI) — which helps research libraries in Illinois share collections and expertise — nearly had to shut down because “their budget was cut by several million dollars” at a state level, said Malone.

Before the budget cut resulted in the network’s demise, however, some of the legislators realized they regularly used resources from CARLI, “they just didn’t know the name of it,” Malone said.

“So there was a lot of turmoil for a couple months, and then all of a sudden the funding reappeared, because there was a connection between something on paper on a budget sheet and something in daily life,” said Malone.

Because of this, the American Library Association and Michigan Library Association have been working to increase awareness so people “can connect a federal agency and the potential loss of funding to it…and people getting their latest novel, or access to a research database, or other materials that they get through Mel-Cat,” said Malone.

Both Malone and Dawe encouraged people to talk to their representatives in Congress. “If people do not want these services to go away, they need to voice their concerns to their federal representatives,” said Dawe. “Then they would want to talk to their state legislators and see if funding could happen through the state.”