Content warning: Discussions of suicidal ideation and death.

When I first came to prison almost 10 years ago, I had what turned out to be a prophetic phone call with my mother. Being 48 and looking down the barrel of a 23- to 50-year sentence, I was feeling depressed and quasi-suicidal. I was grieving the fact that the life I knew before was dead. My mother was feeling pretty much the same way. As we spoke on the phone, we ran the numbers and came to realize that I would be 71 when I reached my earliest release date. She would be 91. My mom, trying to brace me for that reality, said, “Honey, I probably won’t see you free again.” I responded, “Mom, you never know how much time you have.” At that point, a computer-generated voice interrupted our conversation to let us know that our 15-minute phone call was about to end and said, “You have one minute remaining.” I immediately said, “Or maybe you do know how much time you have.” We both laughed.

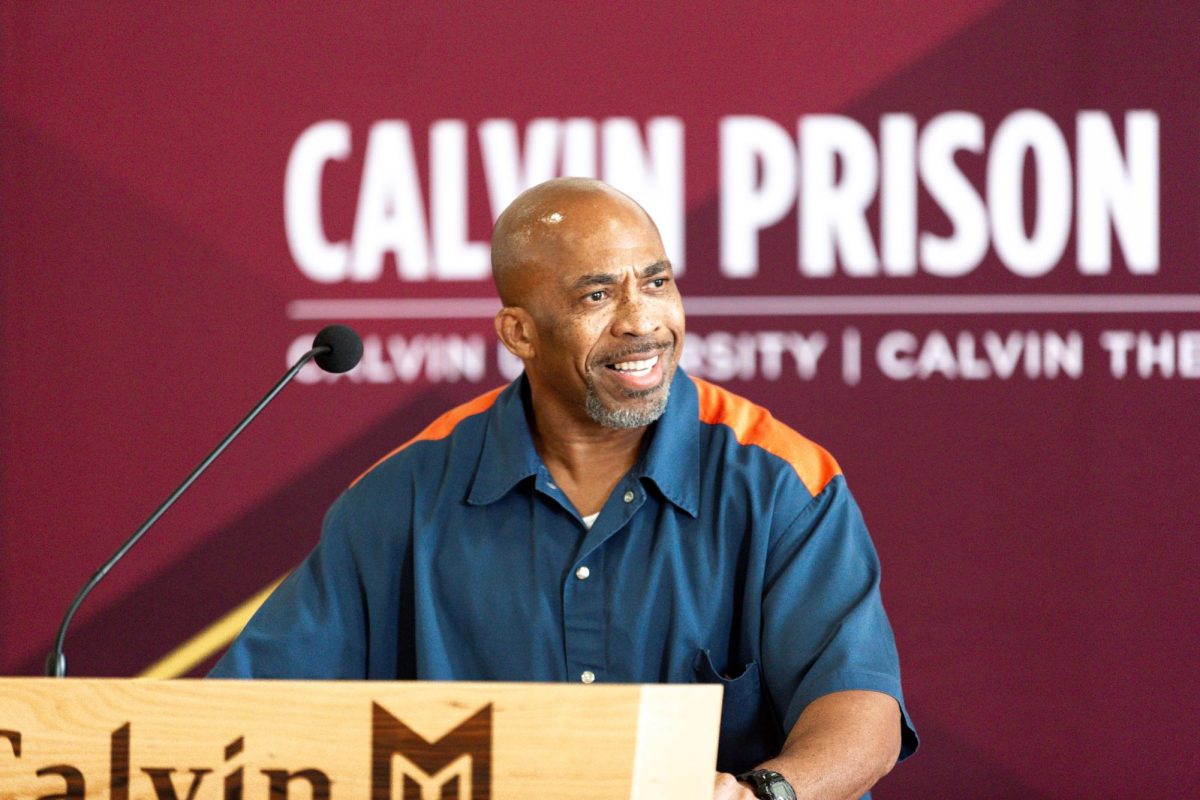

However, much as she predicted, I lost her 9 years later. It was the most devastating loss I had suffered to date. Having come to terms with my sentence, I had built a peaceful life in prison. I was in the Calvin Prison Initiative, and the three people who still supported me were proud. Mom was their leader. This was my tripod of support. The people at church knew everything I was doing — Mom made sure of that. In fact, she would tell anyone who would listen about my progress. She was always there for me, whether that support meant writing to me several times a week, picking up the phone whenever I called or stopping in for a visit. Until suddenly she wasn’t.

On Thanksgiving 2022, she told me that she had stage four uterine cancer. I knew instantly that I would not see her again. I prayed anyway. After weeks of radiation, when it looked like she was going to beat the cancer, I began to have hope. I spoke to her on the phone one day and she told me the good news about her cancer, but she was having a hard time catching her breath. I was concerned and urged her to go to the hospital. She insisted she was fine. Later, when my brother returned home, he saw she was in distress and made her go to the hospital. It turns out that the lifesaving, cancer-killing radiation had accelerated the deterioration of her lungs. This was something that no one could have predicted. A month later, two of my younger brothers had to decide to pull the plug.

The sorrow and guilt came flooding in. Because of my poor choices, I was not there to hold my mother’s hand while she passed away, as she had held my hand through my incarceration. Because of my poor choices, my brothers had to make a decision that should have been my responsibility, being her oldest son. Because of my bad choices, I was not able to attend her funeral. Because of my choices, I could not help my daughter grieve for her grandmother while she held her hand as she passed away.

My tripod of support was missing a leg. I was devastated. I was cut off from grieving with my family and living in a place where tears are a sign of weakness. I felt so alone.

But was I alone? As it turns out, I was not. My CPI brothers gathered around me in a circle of support. I felt blanketed in the love of God that was concentrated through them. I have only felt such love before from very few people — three, to be exact. But there surrounding me were a group of guys that I did not even know four years ago, showing more love for me than the people I share DNA with seemed capable of. Every one of them has been through this type of loss before. Every one of them had real empathy for what I was dealing with. However, the support did not stop with my fellow students.

CPI staff stepped up in ways I had not expected. Professor Dale Cooper made a special effort to come in and provide me with some much-needed pastoral care. CPI administration and staff all checked in with me. Although I did not expect to receive this love, I should have; this is the mission of the CPI program, and all involved live the theology they profess to stand for. My mother lived this same theology and strived to instill it in me. This is the theology that I stubbornly refused to acknowledge or make part of my life until I lost everything I thought was important. It took me coming to prison to figure this out. It took CPI not only telling me about our imago dei but also showing me what it looked like. I will be forever grateful for the love and support everyone in CPI showed me. It gave me purpose. That purpose is to do for others what CPI and Mom did for me — to help people realize they too bear the image of God and deserve shalom. I know Mom would be proud.