“Where is home for you?” After being asked this question, Daniel Chae, seated in the Chimes office, laughed. “That’s the ultimate question,” he said. “Geographically, I would say my home is Kenya.”

Chae, a sophomore, is a missionary kid (MK). He was born in South Korea, but moved to Uganda where his parents are missionaries when he was about three. When he was in fifth grade, he moved again to a K-12 boarding school with about 500 students in Kenya to complete grade school.

MKs are a subset of what are known as third culture kids (TCKs), an identity which also includes the children of military members and other people who live abroad, recent immigrants and other people who grew up between two cultures. According to Grace Hsu –– an MK born in the U.S. to recent immigrants from Taiwan, but was raised in Taiwan and other parts of Asia –– the term describes the “issue of belonging” that arises for many MKs and other TCKs.

“You’re part of two cultures, a culture that you were raised in, which is overseas, and the culture that you’re originally supposed to be from…and you have this third culture phenomenon where you’re not really belonging anywhere,” said Grace Hsu.

Exact numbers on TCK and MK population at Calvin are unavailable. According to Jane Bruin, director of the Center for Intercultural Student Development (CISD), Calvin keeps data on Americans raised abroad, but “does not distinguish people who are dual citizens or non-US residents living in an address country outside of their citizenship country.” Bruin said there are “quite a few” MKs who are not U.S. citizens, many of whom come from South Korea, India, Pakistan, Ghana and Nigeria.

This international/MK overlap reflects some larger trends in Christian missions. According to a study published in 2020, the U.S. is still the largest sender of Christian missionaries, with about 135,000 missionaries of U.S. origin working worldwide; South Korea, the third-largest sender, has sent 35,000; Nigeria, the fifth-largest, has sent about 20,000, and India, the eighth-largest, has sent about 10,000. (These numbers include both missionaries working internationally and domestically.)

The reasons MKs come to Calvin vary. Hsu said her brother attended and she liked their speech pathology program as well as the “international student population and focus on diversity.”

Chae mentioned that Calvin was “very intentional” about recruiting at his high school; at least one student from a previous class at his school came here, and five other students from his graduating class also came to Calvin.

All MKs and TCKs — including those who are U.S. citizens — are invited to join International Orientation (Calvin’s program to help international students adjust to life in the United States) though it is not required for U.S. citizens. This is “because they often relate to more than one culture,” orientation intern, Jonathan Umran said. According to Hsu, international orientation is a “very important place for belonging and networking with other international students.”

According to both Umran and Bruin, several members of the International Orientation team are TCKs or MKs. Umran, who was born in Egypt to an Egyptian mother and a Canadian father with German, Dutch and Syrian roots, is an MK himself. Esther Kwak, the assistant director of the CISD, also told Chimes that she was an MK, raised between South Korea and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

This year’s international orientation included a session for MKs who are U.S. citizens. However, Umran said the program does not include any programming specifically for TCKs or MKs in general, in part because it “removes the component of choice” for those who may prefer not to be known as MKs or TCKs. Additionally, the relatively high percentage of TCKs at International Orientation means that “there’s just so much shared experience that it comes out in conversation,” according to Umran.

For many MKs and TCKs, just meeting other MKs and TCKs can be an important experience. “A lot of TCKs say that the place where I feel the most belonging is with other TCKs, because this is a group of people that understands the in-between experience,” said Hsu. Kwak, a Calvin grad, said that not being the only MK/TCK was a “huge encouragement and assurance” for when she was a student.

“It’s easier to talk to people who have similar roots and similar kind of cultural confusion than people who are monocultural,” said Umran.

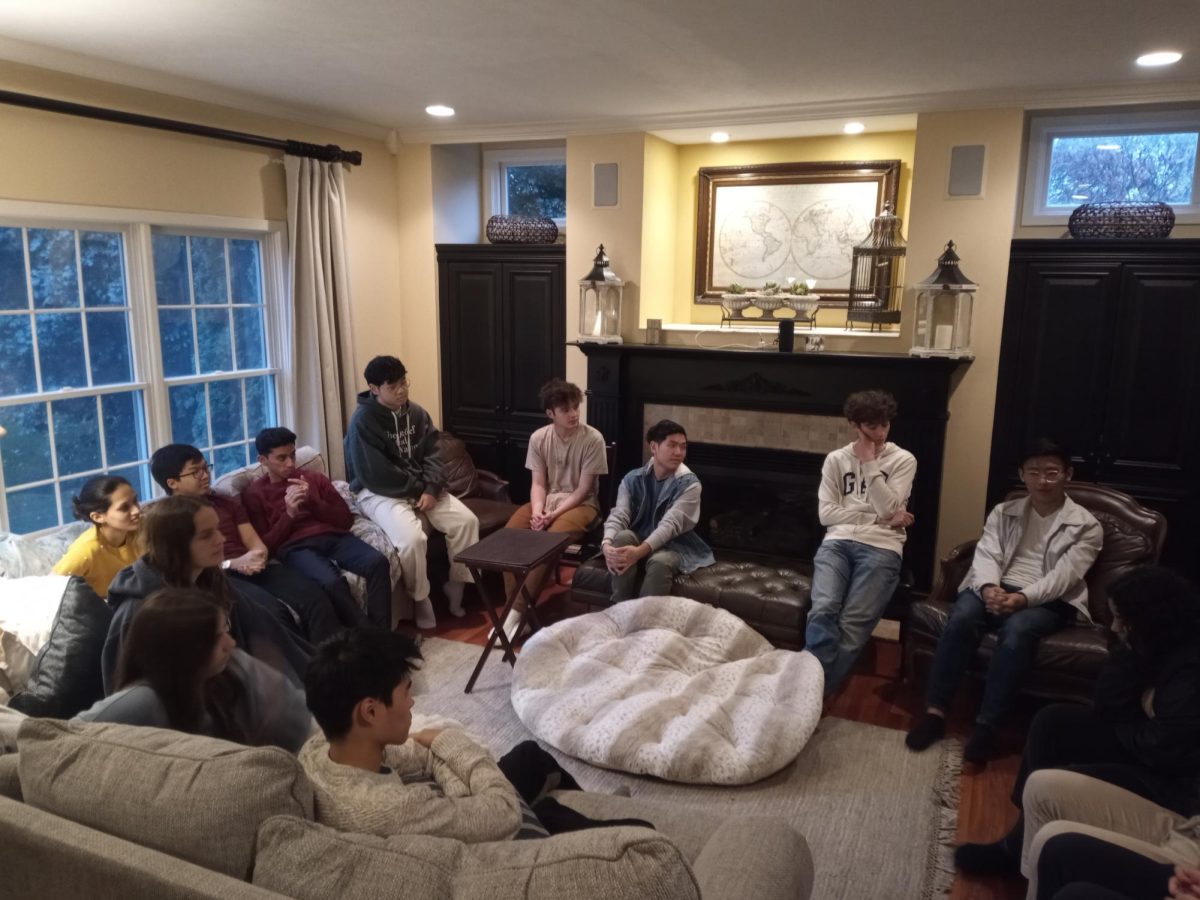

The opportunity for MKs and TCKs to meet each other after orientation is in Mu Kappa, a student organization whose leaders include Chae and Hsu. Chae said the organization is “something [he] really enjoys.”

Because of the tension between Hsu’s American identity and her Taiwanese identity, Hsu said that “the only place that I’ve felt a ton of belonging is in the missionary kid group, so with my missionary kid friends and Mu Kappa.”

Chae said that he knew a lot of U.S. friends at his high school and came to the U.S. assuming that this would help him adjust to the U.S. faster. However, when he arrived, he found the U.S.-raised students “less genuine [and] more shallow” than he expected. He also said that he didn’t always relate to the other Korean students — many of the other Korean MKs had more connection to South Korea than him — and “didn’t necessarily want” to be “stuck in Korean culture.”

According to Umran, having people “pigeonhole” you as one culture or another is not uncommon for MKs. Umran said that MKs who are U.S. citizens, especially white U.S. citizens, often get told they’re just American “even though they have a whole different side to them.” Hsu said that MKs who are not U.S. citizens are often assumed to be just international students. Umran said he doesn’t “think a TCK can completely claim a culture like 100%,” but “if you’ve loved a place, you’re allowed to claim it.”

“It’s okay to be all these things, and people should recognize the complexities of the story a little more,” said Umran.

Umran also said that the experiences of MKs can vary widely; even MKs with superficially similar backgrounds may have had very different experiences. “The deeper you go, like with every story, the more you’ll realize –– oh, this is less similar than I thought,” said Umran.