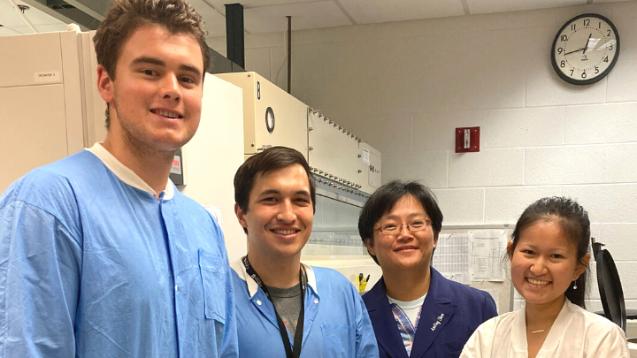

Biology professor and team of undergraduate research in search of a cure for HIV

Biology professor Anding Shen and student researchers have made progress toward understanding the role of endothelial cells in HIV infections.

HIV is currently incurable. Although the evolution of science has seen the manufacture of treatments that target and kill the virus, the presence of latent HIV reservoirs in the body has been an obstacle to scientists for generations. Now, a Calvin biology professor is looking for a way to make progress on fighting the disease. Along with three students, Shen’s latest research project explored the role of endothelial cells in resting T-helper cells, and has concluded that presence of intestinal endothelial cells promotes HIV infection in T-helper cells.

A virus unlike any other

According to the Center for Disease and Control, there were more than a million people living with HIV in the US. Internationally, there were about 37.7 million in 2020. “HIV is a special kind of virus as it attacks the immune system, the very defense mechanism that is supposed to eradicate the virus,” said Shen.

What makes HIV so difficult to treat is its ability to remain dormant in immune cells. When most viruses enter a cell, they reproduce, duplicate and release themselves from the cell, destroying the cell in the process before moving on to attack other cells. HIV, on the other hand, is capable of keeping some dormant duplicates of itself inside those immune cells.

The current goal of HIV medication is to give the immune system a numeric advantage over HIV, by greatly reducing the number of HIV that immune cells have to fight. But if those HIV medications are stopped, the HIV duplicates that lay dormant in infected immune cells are activated and HIV quickly outnumbers the healthy immune cells once more. “With other viruses, you are either defeated by the virus, or you overcome it within a short amount of time. But with HIV the battle drags on for years, and eventually almost everyone loses,” said Shen.

The presence of HIV reservoirs means that without continuous medication and treatment, the HIV in the body of HIV patients will always outnumber and defeat the immune cells.

The targeting and eradication of these HIV reservoirs is a goal for a number of scientists, including Shen. “Our research focuses on the formation of the latent HIV reservoirs and the pathogenesis of the infection in hope that with better understanding, we can develop ways to tackle the reservoir,” said Shen.

Mentoring the next generation

More than 40 years have passed since the HIV virus was first identified in the early 1980s, but for Shen’s student researchers, helping to find a cure is still front-of-mind.

“One of my long-term dreams is to do medical missions work in third world countries … HIV and Hepatitis B are both prevalent throughout Asia and Africa, and that long-term goal continues to motivate my current research,” said student researcher Jessica Eddy. “I want to continue to advocate and fight for a cure for those who cannot fight for themselves.”

Shen told Chimes the search for a cure for HIV may be a long one; this inspires Shen to help young scientists learn the skills and find the sense of meaning and purpose they’ll need in their careers. “Inspiring young minds to investigate and find solutions to tough problems has been a passion of mine, and researching on HIV provides a great opportunity for future scientists to find their passion and calling,” said Shen.

For student researcher Fisher Pham, “Working with Dr. Shen has been one of the highlights” of his undergraduate years. “She pushes each of her students to achieve his or her full potential … and her dedication to her research is truly remarkable, and it is commitment like hers that undergirds all scientific research and development.”