Fewer courses, less Reformed theology: Calvin’s religion department adapts to changing demographics and core

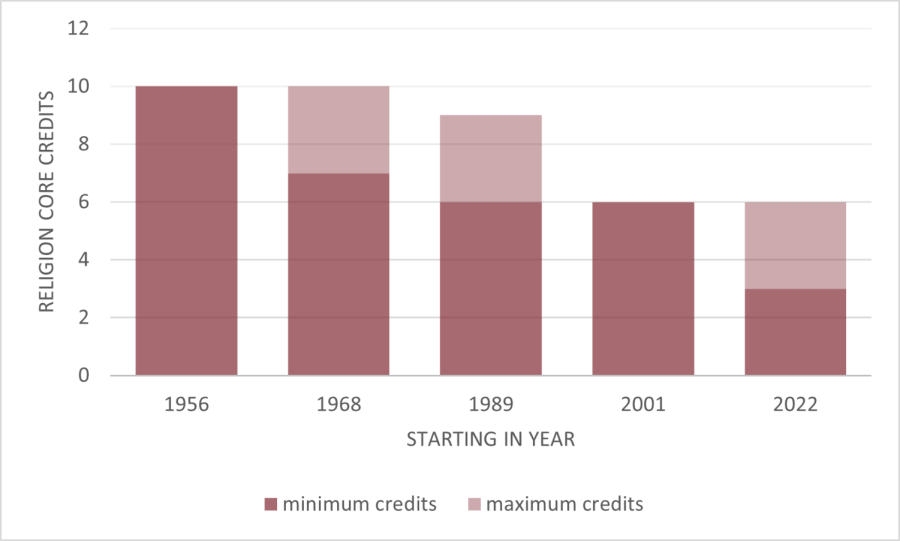

Number of required core religion classes from 1956-2022. (data from archived course catalogs and Kenneth Pomykala)

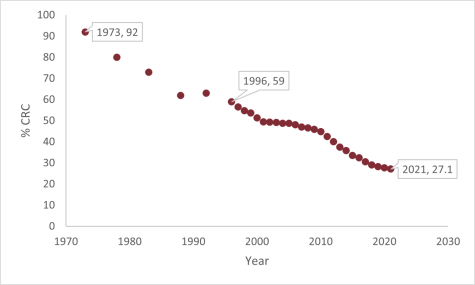

Religion Professor Emeritus Kenneth Pomykala and Dr. Karin Maag, director of the Meeter Center, cite increased religious diversity at Calvin and decreased biblical literacy as possible reasons for Reformed Christian thought at Calvin becoming less ubiquitous in the last 57 years.

Maag said that 40 years ago, “people at Calvin were anchored to the [Reformed] tradition — a deep confessional commitment and vigorous ethnic bonds were definite strengths, but they also contained inherent weaknesses and dangers: a lack of ethnic and religious diversity, a sense that ‘we have all the answers’ and a certain amount of spiritual complacency.” To Maag, the religious diversity Calvin has today is “a real asset.”

Growing up in the CRC, Pomykala attended catechism classes on the Heidelberg Catechism, which formed the foundation of his doctrinal knowledge. However, during his time as a student in the 1970s and his 33-year tenure as a professor, he saw Calvin’s religion curriculum become increasingly basic as incoming students arrived with less and less biblical literacy. A major revision of the religion core happened in 1989. According to Pomykala, instead of taking “a course on John Calvin’s Institutes (REL 206) or on Christianity and Culture (REL 301) … students would take a course in Basic Christian Theology (REL 201).” He said that a lack of familiarity with the basics of Christian theology made the former course offerings out of reach for many students.

Even before the 1989 revision, the number of required religion core classes was on the decline. According to archived course catalogs, from 1956-1968, five courses were required –– Old Testament, New Testament, Reformed Doctrine, Reformed Doctrine 2, and Studies in Calvinism (later called Christianity and Culture) –– three of which were heavily rooted in the Reformed tradition. Over the years, these three courses were eventually cut from core requirements.

Today’s Biblical Theology (REL 131) is designed to teach Christian theology “summarized in the ecumenical creeds and Reformed confessions,” but most are more general overviews and less specifically Reformed than what was offered in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

To Pomykala, the reduction in religion classes is problematic, especially since “in my view, these two trends –– [reduced religion classes and biblical literacy] –– risk weakening Calvin’s aim to equip its graduates for informed engagement and even transformation of culture.”

The number of religion credits Calvin requires has dropped from ten in 1956 to just three starting this fall. “I think six [credits] is barely enough,” Pomykala told Chimes.

Religion classes over the years

According to Pomykala, the term “Reformed” theology is multi-faceted. However, the main factors in what makes the Reformed approach to the Christian faith, which Calvin embraces, distinctive is its emphasis on the priority of scripture, as well as the goodness and therefore redeemability of all creation, total depravity, and “a holistic view of redemption” which implies cultural engagement, Pomykala said.

Director of the De Vries Institute and former religion professor Matthew Lundberg said that the purpose of religion classes is to “have this equipping function … for the other 60 years of [students’ lives].” As a religion major who graduated in 1997, Lundberg said that his time at Calvin “has shaped the way that I think and the way that I experience and live out my faith.”

Ron Polinder, class of 1968, said that it was not until his time at Calvin that Reformed thought took deeper root in his life. The “cultural engagement” facet Pomykala emphasized encouraged Polinder to spend his life on what he calls “kingdom work”: working with Navajo people in New Mexico, serving as principal of the high school he attended in Lynden, WA and on Calvin’s board of trustees in the 1990s, and more.

Michael DeGroot, who graduated in 1995, told Chimes he was surprised in his religion courses not by the content but by “how many people could not answer the questions on the test despite the fact that if you had read your Bible or the assigned material, either one, you should be able to pass.”

DeGroot longed to have deep conversations about theology. Having grown up in the CRC, he said that he “came to Calvin looking for people to help me better understand [Reformed theology, but] there weren’t a lot of people who would talk at the deep, Reformed level that I was seeking.” He said he struggled to find that at Calvin in the 90’s.

Heidi Lynn DeGroot, class of 1996, agreed. During her time at Calvin, she asked many fellow students because she wanted to learn more about Reformed theology, but “no one could tell me except for Michael.”

Since graduating, Michael DeGroot said he has noticed more open hostility to the Reformed tradition, now that they have a son who graduated from Calvin and two daughters who are currently attending. There are “way more beliefs that just aren’t even pretending to make a connection with Reformed [theology].”

Stephen Voss, class of 2009, also feels that Calvin University no longer holds strongly to Reformed roots. He said he “learned what Reformed theology isn’t” during his time at Calvin. Having grown up with Reformed theology, he said he was surprised that in his religion classes “a skepticism about God’s word [was] almost encouraged.” This “skepticism” included the possibility of naturalistic explanations for some Biblical events, like a global flood and the Ten Plagues of Egypt.

For Fisher Pham, a current junior studying biochemistry and neuroscience with minors in psychology and ministry, the Reformed emphasis on the priority of scripture is invaluable. He said that Reformed theology remains important because “it’s a system that centers around God’s sovereignty and aims to take the focus off of men and put it onto God completely.”

Though he enjoyed how his religion class on psalms and wisdom literature, which he said taught him “how to read the Old Testament a lot better,” his Religion 131 class on biblical theology was a different story: what his professor taught about Reformed theology was at odds to what he was learning from his pastor.

However, Pham and Katherine Georges, a junior studying speech pathology, both told Chimes that religion classes differ depending on the professor. Georges had a different experience in Religion 131. She said that her professor gave an “overview of Reformed theology” which made her realize “I actually grew up believing that.”

“Religion 131 just really made me love theology … We did learn about predestination and some of the Reformed things, and it felt good to have other people reinforcing the things I believed,” Georges said.

Cultural engagement

Despite changes in Calvin’s religious demographics and the reduced number of religion courses over the past 70 years, Lundberg said there’s still visible continuity.

According to Pomykala, cultural engagement has been and still is very important at Calvin. For example, prior to the late 1980s, many students, including Polinder, took a course on “Christianity and Culture,” which Pomykala called “the bread-and-butter core class.” According to Polinder, this is because it incorporated “the history and application of the Reformed faith.”

“I have fretted a little bit about whether or not students nowadays are getting enough religion if the requirements have dropped too much,” Polinder said. According to Polinder, courses emphasizing the Reformed tradition have largely been removed from the core curriculum.

According to Maag, there is much to learn and appreciate about Reformed theology because, “At its best, the Reformed tradition is not static, or dusty, or dull. It is vibrant, committed to engaging all the resources of mind and heart under God’s sovereign care to respond to the needs of this world.”

“It still is my hope for today that kids who come to Calvin … catch [onto] this great way of looking at this world,” Polinder said.