Profs weigh in on QAnon conspiracy

Courtesy of Marc Nozell from Merrimack, New Hampshire, USA Wikicommons

““Q Clearance Patriot” or “Q” is the anonymous broadcaster of QAnon information, claiming to be a high ranking intelligence officer in the US government.”

After the attack on the Capitol, many Americans heard for the first time about QAnon, the conspiracy theory that holds that the world is run by a group of Satan-worshiping pedophiles who plotted against former President Donald Trump and consume child victims to extract a life-extending chemical from their blood, all while operating a worldwide child sex-trafficking ring.

“Q Clearance Patriot” or “Q” is the anonymous broadcaster of QAnon information, claiming to be a high ranking intelligence officer in the US government. “Q-drops” is the constant term for Q’s posts, but the sites used to upload posts change over time. It is unknown whether Q is a single person or multiple.

Believers think top military generals conscripted Trump to run for president in 2016 to disband those in the Satan-worshiping pedophile ring, end their control of media and politics, and bring them to justice.

These ideas may seem too bizarre to believe, but Dr. Paul Moes, a psychology professor at Calvin, said that conspiracy theories are accepted more often than we think. Moes described how the belief grows in a gradual process: people are enticed by peripheral issues, such as sex-trafficking, abortion and so on. Then, the foot in the door phenomenon can occur, establishing small agreement on an issue which draws people into wanting to hear more, according to Moes. As the process continues, confirmation bias grows.

“[Confirmation bias is] the tendency that we all have to seek information that confirms our well held beliefs and to either deny or to spend less time considering information that challenges our well-held beliefs,” explained Moes. This fuels conspiracy theories because people will only acknowledge news that confirms their beliefs. Moes is hosting a presentation, “Why People Believe Crazy Things: The Psychology of Science Misinformation,” Feb. 9 at 7 p.m.

These beliefs especially grow when people feel threatened. Within the past few decades, progressive ideas displaced traditional ones, causing conservatives to feel insecure. Dr. Randall Bytwerk, a professor emeritus of communication at Calvin, explained how this allows conspiracy theories to expand. When people feel confused, they want a simple answer and typically one outgroup to condemn, he said. “Conspiracy theories make sense of the world,” Bytwerk said. Bytwerk noted that “there isn’t a single fact” in it, but people are insistent on their beliefs, so they “retreat into [their] own echo-chamber” for agreement.

The common question, however, is whether Christian communities are more susceptible to these ideas or not. Although the larger Christian community may be concerned by hot topics like abortion or sexuality, Bytwerk does not necessarily think they are more susceptible. “It’s mostly the kind of very conservative Christians, and they feel threatened,” Bytwerk stated.

Dr. Neil Carlson, director of the Center for Social Research, echoed Bytwerk. Additionally, televangelists and prophetic celebrities make money off of spreading oftentimes false information they claim to be supported by God. This misinformation is available for all, Carlson said, allowing it to propagate. Carlson added that QAnon is attractive to some Christians because of its use of symbols consistent with American civic religion.

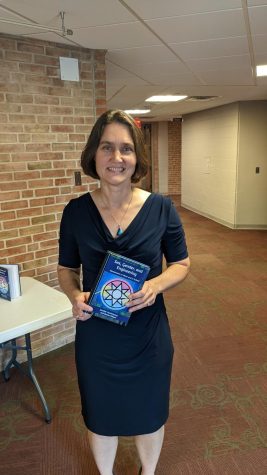

Dr. Kristen Kobes Du Mez, history professor and author of “Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation,” outlined how the connection between Christians and QAnon occurred. “Christians have their own source of truth,” Du Mez stated. There is a separate sub-culture with its own Christian media empire reporting mostly with a Christian lens. “The affinity some Christian evangelicals have to QAnon and other conspiracies can be traced back, at least in part, to a longstanding suspicion of the mainstream media,” Du Mez said.

This distrust creates an “us vs. them mentality,” believing that Christianity is under siege. Initially, these conspiracies were fringe, but now, Du Mez said, they have gone mainstream. Du Mez pointed out that there is a deep divide in the evangelical church right now, and QAnon, especially after the violent insurrection on Jan. 6 at the U.S. Capitol, is deepening those rifts. Du Mez described evangelicals as historically considering themselves to be the “faithful remnant,” feeling the need to fight against Satan. But as the rifts continue to grow, she sees the possibility for change. “I think what we’re seeing now is a kind of realignment within American Christianity,” Du Mez said.

Eleanor Lamsma • Feb 6, 2021 at 4:57 pm

Is Dr. Moes’ presentation accessible to the public? If so, how? I’m referring to “Why People Believe Crazy Things: The Psychology of Science Misinformation,” Feb. 9 at 7 p.m.

I know of a few people who are interested.

Thanks.

M. Hoekstra • Feb 6, 2021 at 8:43 am

Is it possible that both conservative Christians and Fundamentalists are more susceptible to weird ideas without proof because Christianity also demands assent to doctrines witch are unprovable. Does faith itself precondition the believer to believe the unbelievable? Its most important tenants, the core of fundamentalism and more sophisticated theologies are total nonsense to nonChristians: virgin birth, miracles, resurrection, ascension, universal judgment, blood atonement, Satan’s influence on world affairs, a second, the coming after two thousand years. An organization of pedophiles and sex trafficking is more believable since we know that these occur, alhough probably not in the basement of a particular pizza joint.