Snappy dialogue can’t save “The Trial of the Chicago 7” from bad directing

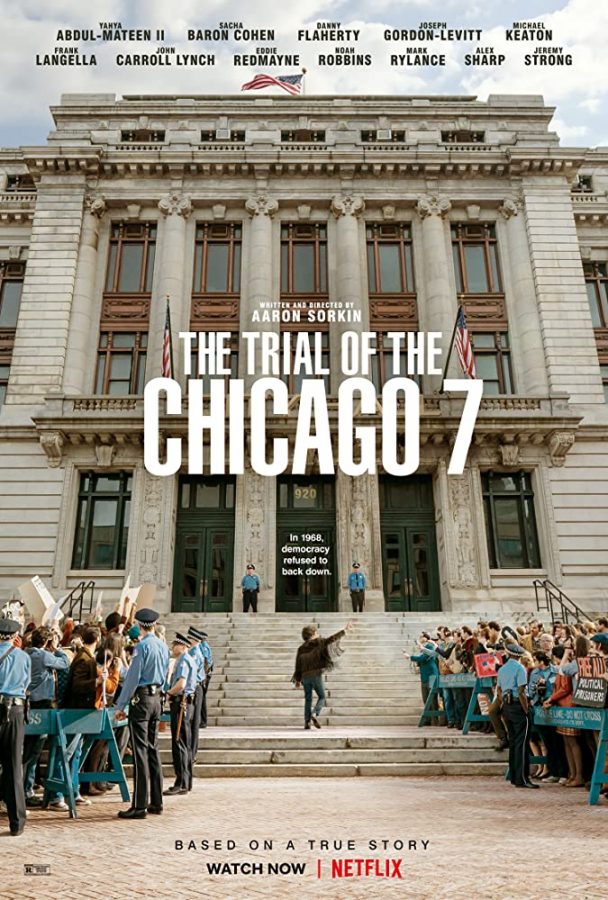

There’s a fine line between making a film widely accessible and pandering to an audience, a line directors must toe carefully when producing inspirational historical dramas. This line is crossed when a film concludes with a freeze-frame matched with swelling, emotional orchestral music and a ‘where are they now?’ epilogue slowly fading on and off the screen, like the dusty old film slides in your grandmother’s attic. Unfortunately, this is exactly how Aaron Sorkin chose to end his most recent film, “The Trial of the Chicago 7,” burying a promising screenplay and a few standout performances beneath a generous layer of directorial ineptitude.

Well, maybe that’s a bit harsh. Credit where credit is due, Sorkin is a good writer. He also knows what he’s good at: straight-forward, fast-paced dialogue, not intricate subplots or deeply developed characters. “The Trial of the Chicago 7” revolves around the trial of seven activists who were charged by the U.S. government with inciting the riots that followed anti-Vietnam War protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. The trial was extremely corrupt and meant to intimidate protestors and the verdict was quickly overturned by the court of appeals, but it has many parallels to protests we’ve seen in the past year. Sorkin’s dialogue-driven style works perfectly for a courtroom drama, but as well-suited as Sorkin is to write this kind of film, he’s not so qualified to direct it.

From Steve Jobs in the eponymous biopic to Mark Zuckerberg in 2010’s “The Social Network,” the characters in Sorkin’s films deliver witty lines and often impressively subvert the status quo. However, as addictive as these kinds of polished characters are, sometimes a film needs a bit more grit to be enjoyable. In “The Trial of the Chicago 7,” the line between good and evil is far too clearly defined; the so-called “Chicago Seven” are perfectly innocent and the prosecution is entirely evil.

Near the start of the film, the attorney general tells a federal prosecutor that he would like to indict the Chicago Seven with conspiracy to incite violence, despite a federal investigation proving them innocent, establishing that the case is entirely corrupt and doomed from the start. Although this scene is effective, it leaves little uncertainty as to what the conclusion will be. The audience no longer questions whether the defendants will win the case, but rather how they will lose.

Because of this clear definition of good and evil, and the conclusion being spoiled within the first ten minutes, the audience is left yearning for some sort of tension. Viewers know the defendants are innocent, and that the judge is going to rule them guilty, so why even watch the rest of the film?

Sorkin’s direction fails because he attempts to have everything line up too perfectly. He doesn’t explore the loose ends of the story, like the story of Bobby Seale, a member of the Black Panther Party who was made part of the trial despite not being involved in the protests, presumably just because of his race. He also doesn’t explore the individual motivations of the defendants. Sorkin’s script has the elements needed to make the film more emotionally engaging but shies away from these moments. For example, there’s a moment in the film where the prosecution gets ahold of a recording of one of the defendants, Tom Hayden, seemingly urging a crowd to commit violent acts, saying something along the lines of “let blood flow in the streets.” This evidence is damning and the defense has to deal with its repercussions, leading to some tension within the group and resentment toward Hayden. Instead of leaning into the emotion and vulnerability of the defense, he brushes past, leaning further into the idealistic representation of the trial.

And this is a massive mistake. The performances in the film are great, but Sorkin is resistant to giving the characters dimension. Eddie Redmayne and Sacha Baron Cohen are particularly excellent as Tom Hayden and Abbie Hoffman respectively, providing what little depth they can with the parts they’ve been written.

In the last scene of the film, we see the defendants sentenced for the alleged crime. It’s the ending anyone could have seen coming: they’ve been found guilty. But before handing them their sentence, the judge allows Tom Hayden to deliver an allocution, where he reads the names of soldiers who have died in Vietnam. What follows is seemingly Sorkin’s attempt to fit the entire emotional punch of the film into one scene. As Hayden is reading the names, the judge begins frantically slamming his gavel, calling for order, as the entire courtroom, including the prosecution, stands in respect of the fallen. The scene is cheesy and pandering, seeking to manufacture a triumphant ending when there isn’t one. The true triumph for these historical figures came later, when the court of appeals overturned the judge’s previous verdict, but this film doesn’t cover this later trial so Sorkin had to search for some other happy way to wrap up the story. And this scene feels fabricated for a reason: while Hayden did in fact read the names of the fallen soldiers in court, it was during the trial, not during sentencing, and the judge stopped him after only a few names. Had Sorkin embraced emotion earlier in the film, perhaps the ending wouldn’t have felt so forced, but unfortunately it’s just the facile cherry on top of an otherwise interesting narrative.