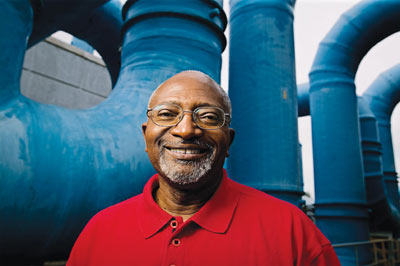

Considered by many to be the Father of environmental justice, Robert Bullard presented on Monday in the chapel as the culminating speaker of the Just Citizenship series with a talk focused on climate change and the social justice ramifications of pollution.

Bullard, a highly distinguished environmental sociologist — he received his Ph.D. from Iowa State University, was granted the John Muir Award from the Sierra Club among a number of other awards and has written eighteen books to the date — argued that climate change is a human rights issue as much as segregation and inequality are.

Though the data on climate change overwhelmingly suggests that global temperatures are fluctuating at a dangerously rapid rate, and that this alteration is primarily human-caused, a vibrant skepticism still keeps significant, unified action from becoming a reality in the United States.

“When we think of the issue of climate change we often look to the physical scientists who tell us the physical facts. We need biologists, chemists and geologists to gather and interpret reliable data,” said Matthew Walhout, the dean for research and scholarship at Calvin College. “But if we want to understand how people will be affected by climate change, and if we want to know which people will be affected most by it, then we should look to the human sciences like geography, and sociology.”

Environmental justice focuses primarily on the questions Walhout mentioned: who produces pollution, and who deals with the adverse effects of pollution most severely. And climate change, a direct result of excess pollution largely produced by the world’s wealthiest residents, will affect the poor most severely.

“Climate change is more than parts per million and carbon; it’s also about justice. Climate change is a human rights issue,” said Bullard. “Clean power is about environmental justice.”

Climate change certainly has global repercussions, but its effects are also dealt with tangibly on a local scale — and these effects are not equally distributed across the U.S., argues Bullard.

Bullard’s studies in environmental justice began after his wife pressured him to conduct a sociological study of the distribution of waste in Houston, the city they were living in the late 1970s.

“From the 1930’s up until 1978 when the study was conducted, 83 percent of all the waste dumped in Houston was dumped in predominantly black neighborhoods,” said Bullard. This trend, it turned out, was common not just in other cities in Texas, but in every city across the United States. “America is segregated and so is pollution,” said Bullard.

In response to the current administration’s approach to cutting back on environmental regulation, Bullard holds a strong stance of civil resistance: “We’re not going to let any agency turn the clock back when it comes to environmental protection, when it comes to health protection, when it comes to issues of civil rights and human rights.”

Having just attended the People’s Climate March in Washington D.C. on April 29, Bullard also noted how energized he was after participating in a display of resistance with a crowd of young people committed to advocating environmental justice and standing against climate change.

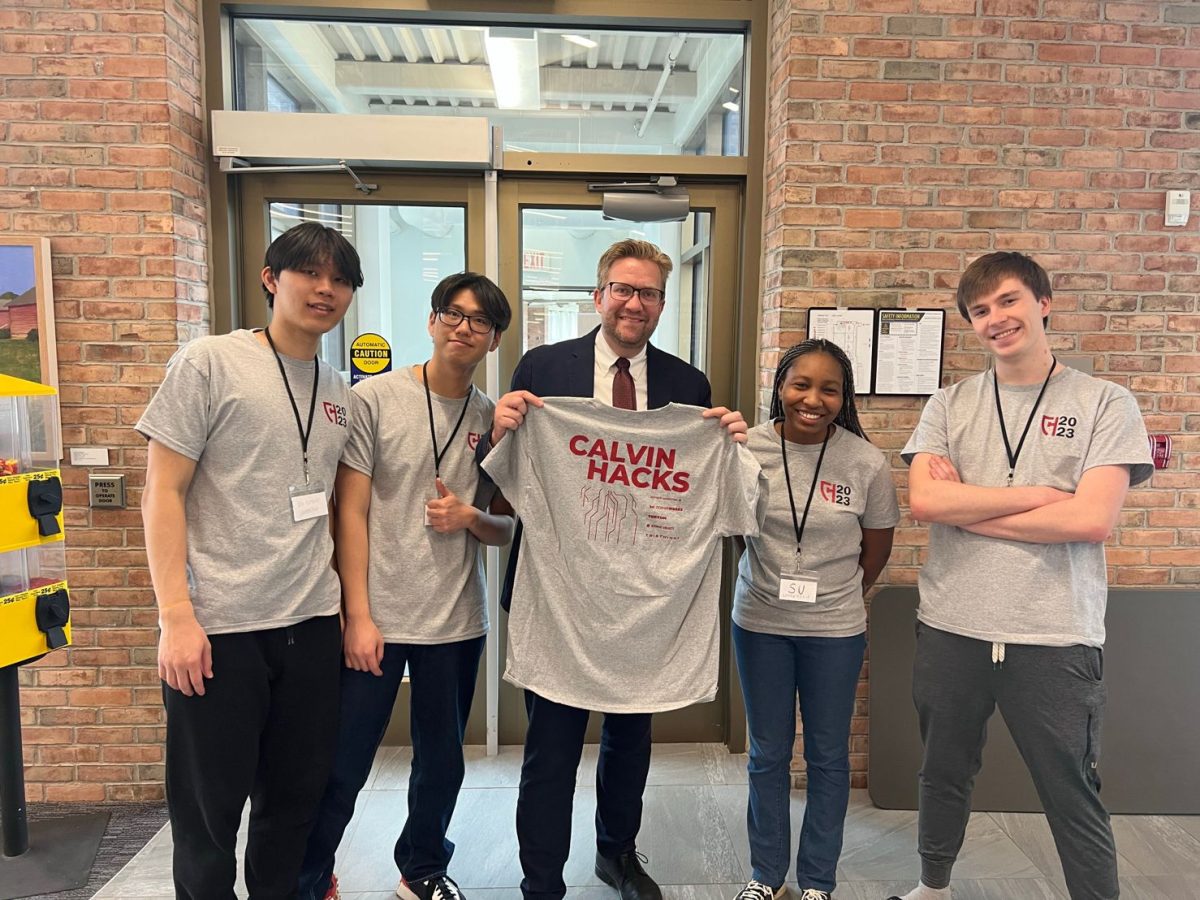

“Every social movement that has been successful has had a strong youth and student component. Dealing with climate change and dealing with environmental justice is no different,” said Bullard. “Young people must own these issues.”

Bullard is a self-proclaimed optimist, but he knows that creating a better, more just society does not happen overnight.

“This is not a sprint. I’m a marathon runner,” said Bullard. “And there’s a race that needs to be run that doesn’t even exist today. It’s called a marathon relay. You run the 26 miles, you pass the baton off to the next generation to run that 26 miles.”

Though the environmental justice has progressed in the United States, there are still significant changes that need to happen, argues Bullard. Even still, his optimism remains: “I’m confident that we will run this marathon and we will cross the finish line victoriously.”

It is that sort of unrelenting optimism from a man that has studied such a great deal of injustice that keeps movements alive.