This year, Calvin’s retention of AHANA (Asian, Hispanic/Latino, African, and Native American) students dropped five percentage points, according to the Day 10 report released last Wednesday.

“I have seen a great number of students who started at the same starting point, but they’re not going to the finish line,” said sophomore Kelsey Waterman. “A lot of my minority friends that came in with me are not here anymore.”

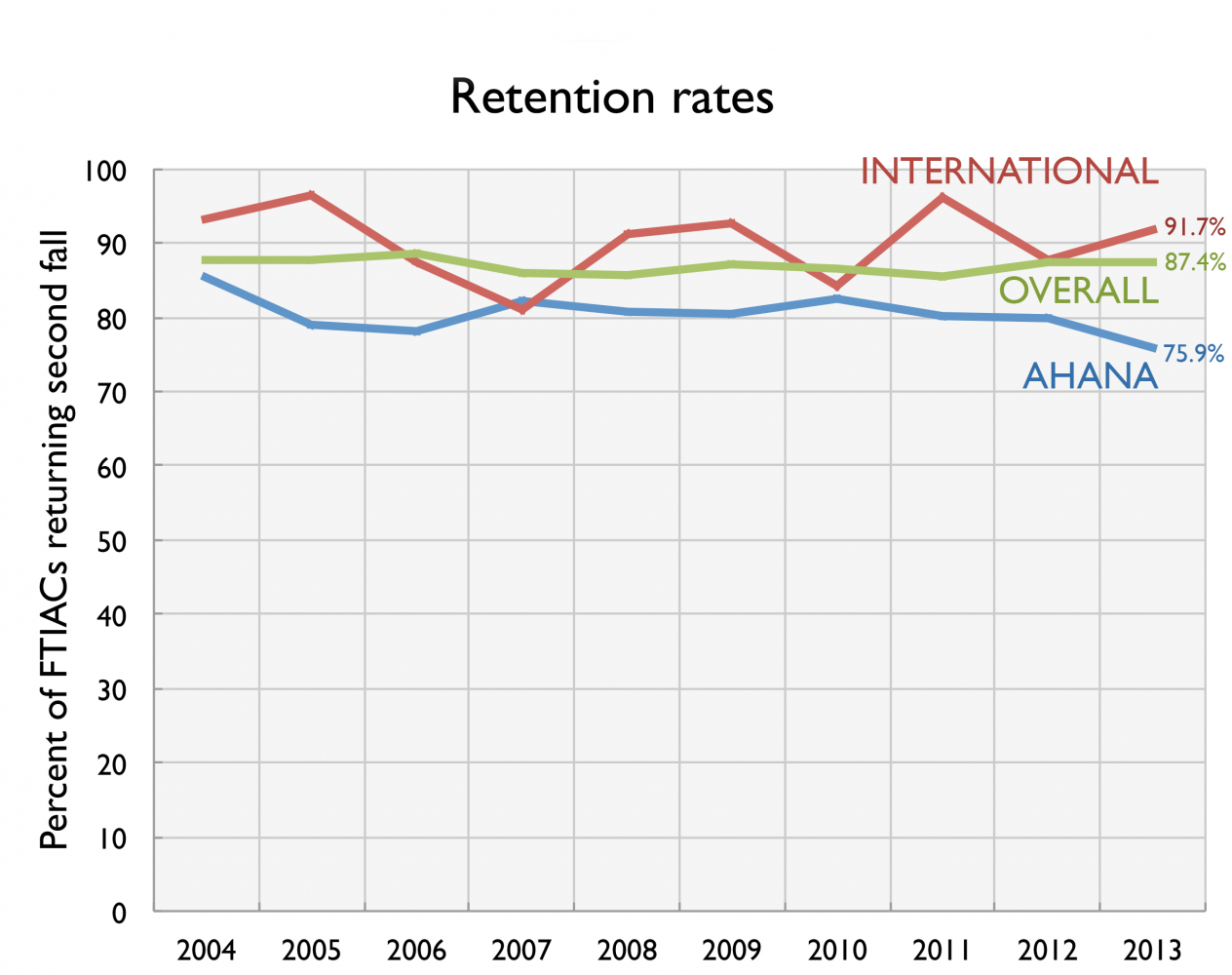

Seventy-five percent of AHANA first-year students returned for a second year, compared to a total average of 87.4 percent for all students, and 91.7 percent for international students.

“Was it a surprise? No. Was it disheartening? Yes,” said Michelle Loyd-Paige, dean of multicultural affairs.

“Our attention has been drawn to the gap,” said Loyd-Paige. “We made sure that the strategic plan had it as a top-level concern.”

Calvin’s new strategic plan prioritizes “strategies… that promote the retention of AHANA and international faculty, staff and students.” However, students question the effectiveness of these structures.

“I had a professor that said ‘Diversity is not bodies in a room, but perspectives represented,’” senior Jeremy Smith said.

In his experience, Smith has seen a lack of diversity in the perspectives and cultures of people in higher positions at Calvin. “You have people from the outside looking in saying, ‘how can we serve you?’” said Smith, referring to the desire of white faculty and staff to participate in making the college a more welcoming place for minorities. But “they aren’t stepping aside, allowing people, or trusting people, to step into those roles themselves.”

AHANA students know coming in that Calvin will be predominantly white, Loyd-Paige says. But before they come to Calvin, they may not have “felt the sting of being an under-represented person, and they come here and feel it,” she said.

Imbalanced numbers – Calvin is only 13% U.S. minorities – means minority students may face misconceptions about their race from white classmates. “It is more an issue of ignorance than prejudice and racism,” said sophomore Eckhart Chan.

In answering classmates’ frequent questions about his experience as a minority, Smith is committed to “being sensitive and courteous.” But, he says, “It’s exhausting.”

Last spring, hoping to start a campus-wide dialogue, students formed We are Calvin [too] to publicly share microaggressions they had experienced because of their race. As a result, one microaggression workshop, offered as part of required workshops for faculty and staff, had to be moved three times as more and more people signed up, Loyd-Paige reported.

This growing interest may be the first step to change. “The easiest thing to work on is the individual,” said Loyd-Paige. “What’s more difficult to work on is cultural and structural.”

“I suspect that there is a mismatch between the way we are defining the problem and the solution we are offering,” said Loyd-Paige. “When the problem and solution are aligned we will see progress.”

Some current AHANA students see this progress as a long process. “Retention is something they will have to work on over time,” said Waterman.

“White people and minorities have two different roles to play. For white people, be open to experiencing new things. Think before you speak, but also don’t overthink. Just be you: I want to meet who you are, not your cautious white self,” said Chan.

“I think for minorities, it’s easy to blow things out of proportion sometimes,” Chan continued. “You have to come in at a higher level, with more grace, willing to withstand people’s ignorance. Professors are here to help you, resources are here to help you, but you might have to put in the extra effort.”

Smith also sees compromise as part of the answer: “On the white side, there’s a temptation for guilt, but let’s work through that guilt. On the nonwhite side there’s a temptation to anger, but let’s move past that anger.”