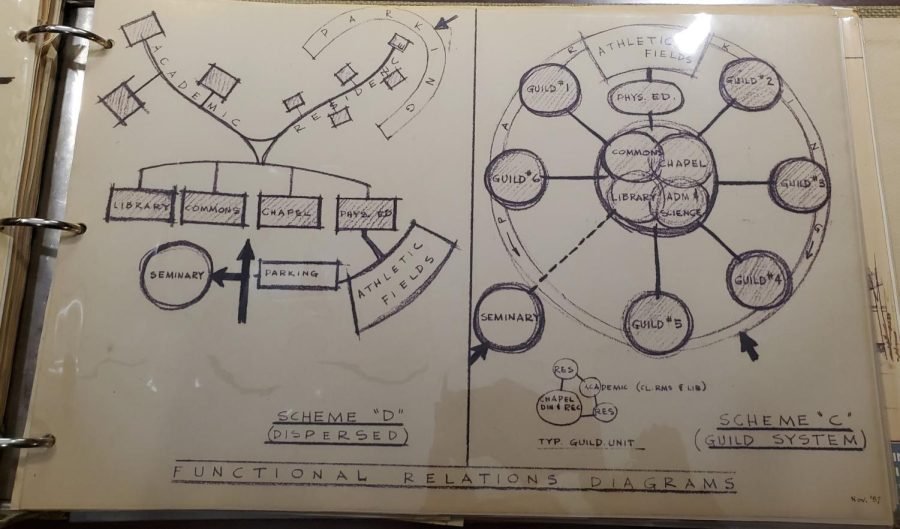

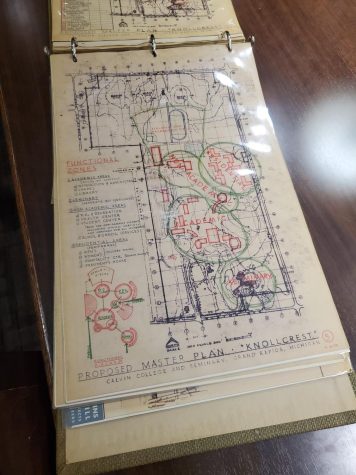

Photo courtesy Gabrielle Freshly

Calvin’s current campus design, with two pods of buildings arranged around common spaces, won out over alternative options, pictured here.

Calvin’s architecture and identity have evolved, and continue to evolve, side by side

October 2, 2022

Calvin’s student body is becoming more diverse, less Reformed and representative of a wider range of types of learners, but Calvin’s historical student base also remains significant on campus and to enrollment strategy. Meanwhile, new campus plans imagine spaces loyal to the historical architectural style but with a new sense of openness and light. As campus evolves, the past and the future are in dialogue.

Foundations

In 1956, Calvin College — under the leadership of President William Spoelhof — purchased Knollcrest farm. Calvin’s campus at the time was located on Franklin Street, in the heart of Grand Rapids. But after World War II, the college had experienced a period of intense growth — so much growth that the Franklin campus began to feel claustrophobic.

“Spoelhof was projecting in the future that Calvin’s intense growth would continue,” said art history professor Craig Hanson, who conducted research on Calvin’s architecture this past summer. Knollcrest farm — the site of Calvin’s current campus — offered ample opportunity for expansion.

Spoelhof turned to architecture firm Perkins and Will, which Hanson described as “the most progressive architects for education,” to design and build the new campus.

“Spoelhof goes to [Perkins and Will] with the intention to produce a modern campus,” said Hanson. “I take Spoelhof’s aim, above all, to be cultural engagement — an assertion that, whatever is going to happen on this campus, it will matter in the present, not in the past. And, implicitly, it will matter in the future.”

The firm assigned architect William Fyfe, a student of Frank Lloyd Wright, to the project.

Fyfe was a proponent of Prairie style architecture — a style focused on the integration of buildings and landscape via elements like flat roofs and natural colors. “The buildings aren’t supposed to dominate,” said Gabrielle Freshly, one of Hanson’s student researchers. Instead, “they’re supposed to look like they’re springing up.”

The design and construction of Knollcrest campus took place in a period when the Christian Reformed Church in North America was beginning to think more intentionally about preserving the unity of its community, and members’ commitment to it.

The community had largely Americanized and become more middle-class and prosperous, according to Calvin archivist Will Katerberg. Leaders worried that its relative isolation as an immigrant religious community would no longer hold it together.

It made sense for campus architecture to reflect and reinforce the desire to intentionally create community. In the years since, the way that desire manifested in campus designs has often been interpreted as campus having a “closed-in” feel.

A vision of insider hospitality

Calvin’s campus has sometimes been understood as an “insular community,” Hanson told Chimes.

“Calvin’s campus, then, was defined by paradoxes: both closed-off and welcoming, both American and Dutch.

“There’s a real coherence to it and in a way that you don’t find on other campuses,” Associate Provost Kevin den Dulk said. “And that could be a real advantage for us. But it can also be a problem if we’re trying to be inviting from the outside.”

When the campus was constructed, it was geographically separate from most of Grand Rapids. “Campus was pretty isolated,” Freshly said. “At the time, it was at the edge of town.” If students didn’t have cars, they likely weren’t going anywhere.

The campus faces inward, too. “Entrances are not typically located outside the commons,” Hanson said. This design aligned Calvin with classical European universities like Oxford and Cambridge, which were arranged around “quads”; officials hoped that an inward orientation would also prevent campus from disturbing the privacy of any surrounding neighborhoods, according to Hanson.

Calvin at the time of the campus transition was dominated by the Dutch-American community. “The overwhelming majority on campus in the ‘70s were insiders,” Hanson said. Campus buildings — by Spoelhof’s particular request — didn’t have signs; if you were a part of the community, you’d just know where to go.

“We experience that as snooty inhospitality,” Hanson said — but, in reality, it was intended to be hospitable. “Fyfe had this vision that if you showed up on campus and you didn’t know where you were going, you would ask somebody …. It was a vision of hospitality that depended upon an insider community.”

Calvin’s campus, then, was defined by paradoxes: both closed-off and welcoming, both American and Dutch, both — in Hanson’s words — “embracing cultural engagement” in its architecture and “shrinking away from community engagement” in its location.

Today, the residential master plan, School of Health plans and other forthcoming renovations and constructions are faced with the legacy of that tension: the need to preserve the historical integrity of Calvin’s unique architectural style while recognizing that the close-knit, Dutch Reformed community of the 1970s is no longer the campus’ target audience.

Evolving community, evolving spaces

Construction projects in the last few decades, such as the Covenant Fine Arts Center, have incorporated new features as well as features consistent with Fyfe’s style, according to Freshly. “Fyfe didn’t want campus to look like it was stuck in one particular time period,” Freshly said. “He wanted it to evolve, to be organic, but to have linking elements.”

The architecture isn’t the only thing that has evolved since the ‘70s; Calvin’s student body is no longer predominantly Dutch Reformed. In the 1990s, CRC and other Reformed traditions made up the bulk of Calvin’s student body. Today, CRC, other Reformed and Presbyterian students combined make up less than 30% of the student body. The university does not currently measure Dutch ethnicity specifically.

But just as the architecture has maintained its ties to Prairie style, the ethos and jargon of Calvin has maintained some level of peculiarity; how Calvin people talk and think about education and community is unique. That is both a strength and a weakness, according to Katerberg.

“Once you get inside, and you start to figure out some of this language and some of the characteristics of this community, it starts to make sense, and it can be really powerful in shaping people. But it’s precisely that same thing that can make it a bit hard to fit in, and that can be a challenge when you’re trying to recruit [new community members],” Katerberg said.

“The goal is to add light and openness without sacrificing the integrity of the Prairie style.

Calvin’s Global Campus is navigating how to bring the school’s context-rich tradition into non-campus contexts, such as Handlon correctional facility, online platforms and the city of Grand Rapids, as well as how to make campus more inviting for non-traditional students.

“As I think about our identity going forward, all the work that we’re doing with Global Campus is to think about, well, how do we reach out to other learning communities who are not necessarily living here with us and are already sort of part of the culture that enjoys the space?” den Dulk said. “How do we invite them in, in ways that don’t feel to them like the architecture itself is saying that they’re closed off from a learning experience?”

Den Dulk’s work focuses on adult learners — primarily students who are 25 or older and employed. Making campus welcoming for them means making sure there are spaces where people without meal plans can get food, accessible bathrooms and other features that say “come on in.”

But Calvin’s architectural style isn’t inherently exclusive, according to Hanson; in fact, he said, it has some advantages. “Buildings at the University of Chicago, buildings at Yale — they want to impress you,” he said. “And implicitly, there’s a sense of: ‘Do I deserve to be here? Is this building for me? Am I good enough?’”

Calvin is different, according to Hanson. Campus “doesn’t suggest a kind of mastery of the surrounding landscape,” he said. “It’s not hierarchical. It’s a very peaceful, coexisting form of architecture.”

The various master planning projects in the works aim to preserve this feature of Calvin’s campus while trying to mitigate the feeling of being closed off.

An example of this is Calvin’s residential master plan, which aims to make small tweaks with big impacts to residence hall designs. The goal is to add light and openness without sacrificing the integrity of the Prairie style.

Adjustments like this keep Calvin’s architecture from stagnating, according to Hanson, who gained a newfound appreciation for the dynamism of Calvin’s design after visiting Rockford College in Illinois — Fyfe’s other major architectural project.

“[Rockford College] was one of the most depressing campuses I have ever been to. It was a glimpse of what happens when a campus is not renewed on a decade-to-decade basis,” Hanson said. “I now think of Calvin’s campus — even the parts I’m not in love with — as a sort of ongoing investment. Campus has to be a living, organic thing.”

The future

With the recently completed School of Business east of the Beltline and plenty of future renovations planned for both sides of campus, navigation of Calvin’s architectural legacy continues.

According to den Dulk, the openness and attention to light that the business school entrance features may also feature in the redesign of the science complex as it is renovated to accommodate the school of health.

The university is also in the process of applying to get some campus buildings added to the National Registry of Historic Places, according to Chief Financial Officer Tim Fennema.

That designation will enable the university to sell off about $20 million in historical tax credits, but it will also require that future renovations to those buildings are carefully designed to be true to the historical architectural style. Fennema told Chimes he has been working with Hanson to think through ways to honor that history in future plans.

For Katerberg, the question for Calvin to tackle now is how it’s going to balance its legacy — a context-rich, tight-knit community — with its goals in the present and for the future — a pluralistic, diverse and innovative community.

“As we renovate the campus, how do we, in articulating the mission and vision for Calvin, negotiate the tensions between solidarity and community, and diversity and pluralism?” Katerberg said. “How do we negotiate the opportunities — and both intended and unintended consequences?”