Faith and academics: How some professors pursue faith integration in and out of the classroom

Nursing professor Jesse Moes pairs devotions with class topics.

To religion Department Chair Won Lee, a Christian liberal arts education shouldn’t consist of separate “blocks” of learning, but of integrated classes and disciplines. He said the reason “religion class is so vital and important” is because “you’ve got to have a clear foundation so that you can apply … this foundation of Christianity … in your nursing, engineering, accounting and other things.”

Assistant professor of history Darrell Rohl previously taught for several years at a university which, according to him, was Christian in name only. Rohl told Chimes that coming to Calvin took some adjusting to understand that it was not only acceptable but encouraged for him to lead devotions in class. According to Rohl, the Faculty Handbook states that “faculty are welcome to offer prayer and devotions in their classroom sessions though there’s no requirement to do so.” This is in stark contrast to the university he used to teach at in England, where although the words “Christ” and “church” were in the name of the school, “it was really unacceptable for me to talk to students directly about faith.”

Following the Reformed tradition, according to Lee, Calvin emphasizes three complementary approaches to faith integration: pietistic, doctrinal and social. Classes, chapel and social life at Calvin each have a role in this, Lee told Chimes. First of all, he said the pietistic component means that “what you believe actually has to do with what is meaningful to you personally.” Secondly, “doctrinal means you know what you believe in.” And lastly, social engagement emphasizes Calvin’s oft-repeated phrase of “agents of renewal” — the idea that the Christian life is not merely personal but also societal.

Aware that studying the Bible can be seen as a merely intellectual activity, Lee tries to demonstrate all three Reformed emphases — doctrinal, pietistic and societal — of faith integration in his classes. Lee said that though students tend to assume that a Bible class must be taught from a Christian perspective, “you can teach [the] Bible in a non-Christian way,” referring to how secular universities also have Bible classes. As a result, he stresses a pietistic approach, where students understand how to integrate what they are learning about God into their lives.

While a graduate student at Notre Dame, Clair Mesick, assistant professor of religion, enjoyed learning from professors who showed her how “reading the Bible [was] to think about the big questions of human existence.” Though strong Christians, her professors understood that students coming from all different backgrounds could have something to learn from the Bible. Now a professor herself, Mesick encourages her students to read the Bible for “its philosophical, moral, theological, spiritual insights.”

Understanding the pietistic aspect of Christianity, Jesse Moes, associate professor of nursing, brings faith into his classroom by incorporating “some sort of faith, devotion and prayer.” One of the ways he integrates faith into the classroom is by using “Luke for Everyone” by N. T. Wright. He pairs devotions with class topics, like diabetes and hypertension. “Not every topic has a direct link to a devotional,” Moes said. “I try [to] find a little nuance.”

Like Mesick, Moes’ desire for faith integration both in and out the classroom stems from his own experience in college. Recounting an interaction with his advisor when he was an undergraduate student at Calvin, Moes said, “I remember this very vividly. My advisor had a specific passage picked out. And then she would read that as almost more of an encouragement piece and then we prayed together. And that really had an impact on me.” Now an advisor himself, Moes closes every advising session with prayer, asking his advisees what specifically he can pray for. “Sometimes it’s something as simple as ‘I need to get through this test,’ … or something as profound as ‘my mom has cancer’ … Those are really privileged moments that I get to share with students and they can choose to disclose as much or as little information as they want.”

Jennifer VanAntwerp, professor of chemical engineering, has adjusted how she leads class devotions over the years. “I felt at the beginning like I needed to search the Bible for passages that related to engineering somehow, which is really hard to do.” Acknowledging that there were many in her department who did a very good job of integrating faith and engineering, she desired to share her own expertise. “As I matured as a Christian and as a professor, I was looking for what it is that God gave me to share with students.” Though she may not be as knowledgeable about engineering passages in the Bible, VanAntwerp realized she had something to share from her research into belonging in the engineering profession and her experience growing up in a secular environment.

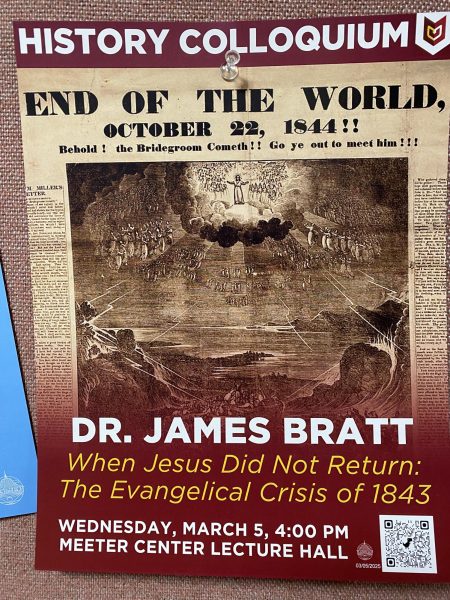

Like VanAntwerp, Rohl integrates his own expertise with faith. “I don’t try to teach history as an approach [to] seeing God [in] all the events of the world,” Rohl said, “Instead, I try to teach [my students] to pay attention to the evidence, to value truth. Even when truth is uncomfortable; even when … the evidence seems to call some of your long-held beliefs into question.”

As an archaeologist, he said one example of establishing honesty is not to lie and tell “people that you know the chariot wheels of Pharaoh’s chariots have been found on the bottom of the Red Sea because they haven’t. Some archaeologists and apologetics groups will say that they have, but I know it’s not true.”

As part of his classes, Rohl also started giving devotions using a book called “Faith and History: A Devotional” in order to show a more explicit integration of faith in his history classes. Rohl said, “each one starts out with a small little scripture passage, a little devotion that relates to that passage, and then whatever the particular historical period place” which makes the devotions especially applicable to his classes, like when studying Christopher Columbus.

Currently on sabbatical to develop a research tool for her research on engineers and belonging in the workplace, VanAntwerp said that her decades of research are fueled by her passion for studying what the “engineering experience is and how we can be better to each other,” especially because “that leads to better engineering.” She recognizes the importance of such studies because there are only, “in an engineering context, about 20 papers within the educational contexts and about 20 papers within the workplace context.” Much like what Lee explained about the third Reformed emphasis — social engagement — VanAntwerp emphasized the importance of belonging: “What interferes with that sense of belonging and … how often are they having those positive and negative experiences of combination of that in order to study that no one really looked at that?” This is a perspective she seeks to integrate both in the classroom and in her research.