Sexual assault exists at Calvin, so do the tools to find healing

April 29, 2021

TW: this story contains references to rape and sexual assault.

To this day, Sarah doesn’t remember what she told the man who assaulted her. It’s a fact she finds haunting—the inability to recollect. She doesn’t recall saying no, but she knows she didn’t say yes to having sex with him. What Sarah does remember, vividly, are the thoughts that went through her head: “Maybe this is what love is… I owe this to him; this is why I came here… Maybe if I just keep going along with it, it will eventually stop.”

She left his house as soon as the encounter was over; something didn’t feel right. On the drive home she felt confused, violated, dirty and objectified. “I had spoken up multiple times. So why didn’t he stop? And was he supposed to stop? Was he supposed to ask if I was okay?” she wondered.

The more she tried to convince herself that her feelings were nothing more than guilt about having gone to meet a man she had met online, the more she knew something was truly wrong with the situation.

“He asked if it was okay, but not really though. It was more like when you’re waiting in line with a friend for a rollercoaster, and your friend is really excited, but you’re very visibly uncomfortable and scared,” Sarah told Chimes. “And they’re like, ‘Oh are you ready? Let’s do this.’ And they’re not as much asking if you’re okay but kind of just like ‘We’re doing this, but I’m going to say the right words.’”

Her name has been changed and her identifying information withheld to protect her privacy, but Sarah’s story is real. More importantly, her story could be anyone’s—your roommate’s, your partner’s, your professor’s or even your own.

For reference, 26.4 percent of female, 6.8 percent of male and 23.1 percent of transgender, gender queer and nonbinary undergraduates experience rape or sexual assault by force, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, the largest anti-sexual violence organization in the U.S.

In the past five years, more than 59 people have reported instances of sexual assault to Safer Spaces, Calvin’s program for connecting survivors to resources and overseeing cases of sexual assault, harassment and violence. During the same time period, Campus Safety received 26 reports of sexual assault including 10 instances of rape, according to crime logs filed under the Clery Act, which does not include reports of crimes occurring outside of university-owned property. In at least 11 of the 26 reported incidents since 2016, the victim knew the perpetrator.

According to RAINN, only about 20 percent of female student victims between the ages of 18 and 24 report their sexual assaults.

When she realized that what had happened to her wasn’t okay, Sarah began looking for help and encountered Safer Spaces. Her report was one of 22 sexual assault reports filed with the program last year.

Sarah met with a member of Safer Spaces who empowered her to write a police statement and speak with others about what had happened.

In the time that’s passed since, she’s struggled to put the pieces back together. The initial chaos of police reports, counseling, preventative treatment for HIV and telling her friends kept her mind from processing the trauma. But as the dust settled, the experience became more real, more difficult to deal with.

It took two months for Sarah to work up the courage to tell her siblings. Her parents still don’t know.

“I’m not your ideal rape victim, because I wasn’t dragged into the woods,” Sarah said. “And the police told me there wasn’t any physical evidence, I wasn’t drugged and I wasn’t drunk, and I was not threatened. One of those three things would’ve needed to happen for them to be able to do anything without it being hearsay.”

But where she says the police questioned the truth of her story, Calvin’s on-campus resources did nothing but provide healing and support.

“I did not expect to be so supported. Everyone at Calvin was amazing and very dignifying and didn’t question anything,” said Sarah.

The same day the assault occurred, she met with an area coordinator who referred her to Safer Spaces and the YWCA Nurse Examiner’s Program in downtown Grand Rapids, which provides 24/7 on-call rape exams and emotional support as well as regular support groups.

“We start our process by listening to the reporting party and giving them as many options and choices as possible about what they want to do next,” Safer Spaces Director Jane Hendriksma told Chimes in an email. “We honor their decisions about participating in an investigation.”

If an investigation is initiated on campus and brought before the Office of Student Conduct, Safer Spaces policies use a standard of “preponderance of evidence.” Hendriksma said this standard does not require proof beyond a reasonable doubt, as in the criminal justice system. Rather, university officials determine whether or not the evidence presented indicates that “it is ‘more likely than not’ that a violation occurred.”

And later, when the man who assaulted her moved only 15 minutes from the university, Campus Safety helped her put in place a no-contact order that would prohibit him from coming on campus.

In addition to receiving reports, investigating claims, and helping survivors make statements to the police, Campus Safety is regularly trained to work with victims of trauma and refer them to resources like Safer Spaces and the YWCA.

Among the protections offered to survivors is Safer Space’s amnesty policy, which is based on the principle that victims should not be blamed for their assault. Under this policy, no disciplinary action will be taken against a student who was drinking or using drugs during an assault.

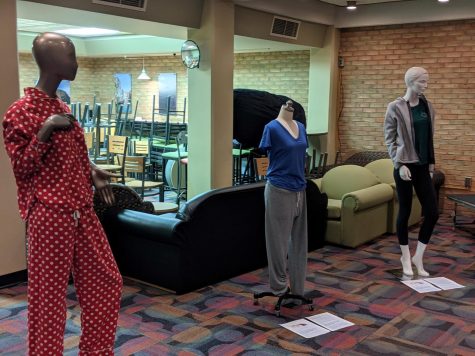

It’s a principle with which senior social work major Tara Boutelle wholeheartedly agrees. It’s why she started “What Was I Wearing?”, an exhibit displaying the clothing survivors had on when they were assaulted as well as their stories.

“I just hope that people realize that sometimes when you ask questions like ‘What were you wearing?’ it can actually place the blame on the victim, as if their clothing can say yes when their mouth says no,” said Boutelle.

The exhibit has been put on at four different schools, including this week at Calvin. Nine Calvin survivors responded to the anonymous survey to take part in the exhibit. And with the support of the social work and gender studies departments as well as local donors, Boutelle assembled replicas of their outfits. Most of them, she said, were normal, everyday outfits. Many were even wearing pajamas.

Boutelle herself is a survivor of sexual assault. For years, she says she struggled to validate her own story because it involved no physical contact.

As a senior in high school, she was invited to a friend’s house to swim, where he secretly filmed her changing and showed it to other students. By the time the police found out, he had already victimized several women, according to Boutelle.

“I felt like it wasn’t valid enough [to reach out for help] because it wasn’t actually physical,” said Boutelle. “It’s really hard when you’ve experienced something that’s been traumatic in your life, and it can be pretty isolating to try to figure it out by yourself.”

The most important thing the Calvin community can do for survivors who struggle with the same confusion and doubt of their own experiences with assault, she said, is believe them.

“It’s definitely not talked about enough, and I think that bringing light to it and making it part of the conversation and the dialogue is important,” said Boutelle. “If it’s just left as a taboo, then nothing will happen.”

“Purity culture increases the shame experienced by victim-survivors, as sexual violence is considered a loss of purity,” Rachel Venema, professor of social work, told Chimes.

In addition to opening up conversations about sexual assault and survivorship, university officials noted Calvin’s preventative programming, including annual education for athletes, video training for incoming students on assault intervention, Rape Aggression Defense training for women, and educational events from Calvin’s Sexual Assault Prevention Team as part of the Sexuality Series.

As she opens up more about her story, Sarah has found conversations to be both healing and hurtful, depending on how people react. Good listening and emotional support have been helpful as she perseveres; harsh words have not.

“The whole idea that you have to be a victim or a survivor, it’s an identity struggle where you feel like you have to be in a certain box where you’re either really depressed or really resilient,” Sarah said. “And if you’re somewhere in the middle, it’s challenging to know where you belong.”

If you or a friend have experienced sexual assault or violence, help is available. Campus Ministries, the Center for Counseling and Wellness, Health Services, Calvin’s anonymous reporting hotline (616-526-4974), the YWCA (616-454-9922) and RAINN hotlines are all confidential resources for survivors.

Resources are also available online at both Campus Safety and Safer Spaces’ webpages.

“It’s a very vulnerable, very strong thing to ask for help,” said Dr. Irene Kraegel, director of the CCW. “No one is an island, no one is successful on their own. And this is especially the case with trauma.”