Transcendence: Prof talks art, icons and being a ‘disruptive witness’

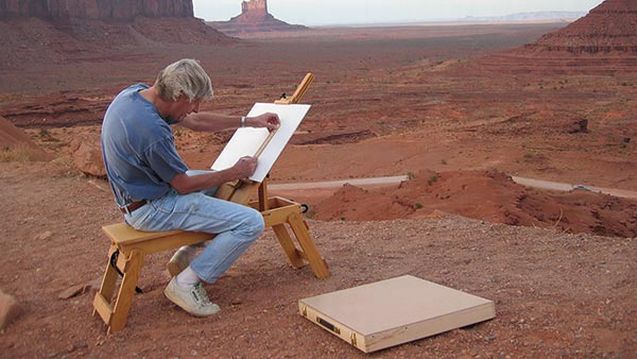

Speyers, who teaches art and art history, credits his experiences painting in Monument Valley with the beginning of his inspiration to paint the west. Photo courtesy Calvin.edu.

‘Franklin Speyers is a professor of art and art history. The Center Art Gallery is showcasing his show “West of the Imagination” through Dec. 20. Chimes spoke with Speyers in the gallery about his inspiration and artistic influences.

Chimes: This is beautiful work. When did you start painting?

Speyers: These works started in 2015 as a sabbatical.

Chimes: Did you grow up in the West, or what was your inspiration?

Speyers: No, I traveled out to the West quite a bit. When I was young I always wanted to be a cowboy. I have a picture of me at ten with some of my paintings. So when you say, “When did you start painting?” it’s hard to say.

Chimes: Is this exhibit representative of your style or are you trying something new?

Speyers: This is pretty straight. I started in 2007 plein air painting in the West and then I realized how little I knew about plein air painting. I sat out in Monument Valley and that’s where I started. The storm was moving over the landscape and it was evaporating before it hit the floor, and I just thought that was lovely and, from there, one thing led to another and I ended up teaching workshops in plein air painting.

Chimes: You describe this unique experience of loveliness. What about a natural experience of a view inspires you to paint?

Speyers: You could pick virtually anything. There’s wonderful painting I’ve done right over here by the Sem Pond. I tell my students: paint what you love, but don’t do the grandest thing, because you won’t do justice to it. [Paint] what you love but frame [it] so that it captures a moment. You have to work with such speed the light is changing constantly you have to look for light; that is what painting is about that’s what these painting are about: light and darkness.

Chimes: You have a lot of wide open spaces where the people are very small.

Speyers: Yes, that was very important. That came from studying Van Ruisdael. You can see his influences — the big skies. I’m very open about listing my inspiration. If you look you’ll say, oh, I see why you do what you do.”

The smallness of the individual, if you’ve ever been outwits on the prairies you locate, you find your location in creation and it is not all that big. When you are in cities, you feel like you’re in control and you’re big. If you’re on the prairie and you see a thirty-thousand-foot storm roll through, and the cowboys are sitting there waiting for it to pass but you get a city slicker like me, and I’m like man, I’m getting out of here. So, you’re dwarfed by the expanse of it all and at the same time it is so quiet. There is a particular quietude you will find there and it’s transcendent, highly transcendent, and so what these paintings try to do is lean against what has been called “closed immanence.”

Chimes: Explain the concept of “closed immanence” a little bit. How does your work engage it?

Speyers: There was an article that appeared in The Gospel Coalition [“The Disruptive Witness of Art”] and it is crazy because it describes [what I’m doing] identically. There is this idea in modern art that there is immanence but not transcendence. It started with Nietzsche who said there is truth but it is ugly. So there is this notion echoed within culture at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century up into the First World War. So much of modern art has been reactionary; it reacts to rather than affirms. Plein air is affirming abstract expressionism is about deconstructing. My paintings [in contrast] are rather realistic we have a new narrative.

Chimes: Yes, they are incredible. Why have you chosen this style?

Speyers: Think of it this way: when Hollywood tries to predict an alien, what does it look like? You have ET or Avatar or a lot of other ones. So the question arises: why do they do these similitudes [to humanity] but not really? What is in their lack of imagination that they can’t come up with anything different? Why that? Why do they conjure up something less than the human form? Well, because there is nothing higher. We are made in the image of God, the most beautiful thing He could make. So for people to deconstruct human beings it is [to focus] on all that is broken.

Chimes: So, what about humanity are you trying to paint?

Speyers: Deconstruction stops there. And that is what I call closed immanence, because it stops there; because it says, “This is all there is.” Art has become a matter of entertainment, the preoccupation of our senses. Why? The same reason as Adam hid in the bushes. How do you not hide? You have to face the transcendences. People will say, “Your paintings are so transcendent,” and that is because reality is transcendent. So that is what I’m doing: saying, “Behind what you see is another reality.”

There are little things hidden in each painting. “Left turn” has a right turn. In “Mine” they are branding a cow. But what does it mean that it is yours? And that’s the point. It is placing the individual, placing it within creation and saying it does not really belong to you.

Chimes: You’ve built on a lot of art history here.

Speyers: Well, I’ve had to build on the precedents that have come before me. And, for me, that’s Van Ruisdael. He came out of the Reformed tradition and I thought, that harkens with me. So I took that out West, and I found that out West, those issues were similar. I can take that American icon, that idiosyncratic cowboy. So the West has this ideal of icons: fifteen to seventeen years of age, underfed, overworked.

For some inexplicable reason we’ve chosen the Cowboy to represent American culture. It is a way to bring order to your reality to harken back to a time, but mine are rugged; they are time-worn. The icon is wearing out. So this is a show about icons, iconography and iconoclasm all at once and it is staged in an institution that has a long history of iconoclasm. We don’t do images [in the CRC tradition] because they are so slippery. This gallery is really a huge leap forward in saying we can have images. So I’ve taken the icons of culture and exposed them to my own philosophical and theological background. I want to be like the article in The Gospel Coalition and be disruptive with my artwork.

Chimes: How so? What will that look like?

Speyers: So in that one [referring to a painting titled “George Custer”], there you have Robert Colbison posing as George Custer and he’s moving off the plan. The narrative of who he is and what he has represented is overturned. We have fuller narrative, increasing information about what has happened in the West and even to this day people want to shy away from it. […]

Chimes: So what advice would you have for students who want to this tradition of painting transcendence?

Speyers: Study art history. The single most important art courses you can take at Calvin is to go study art history and study a lot of it. That is where you find out the greatness of those who preceded you. I think it is very important to fragment and incorporate other artists’ motifs in your own artwork. It is like tying history together with you but contextualizing the issues with you.

It is about what do you want the view to do. Do you want them to walk away; that’s it. Or do you want to provoke them and stir them to think about beyond what there is, what is not visible. I think that is what art students, especially Christian art students [should do]. There is a sort of a call to use their imagery and to use it for a way that glorifies God. It’s a matter of how you do it. You don’t have to do it like I do it. There are two [sides] to art portraiture and nature and Rembrandt was to portraiture what van Ruisdael was to nature and both of them are very transcendent in their work because they painted what was but with their own spin on it and it made you think.

You shouldn’t walk away from this and say “that’s nice.” You want people to come back and think about it. And people have done that. And that is the greatest compliment I can get as an artist.

This interview has been condensed and edited.