Political convention explores diverse views

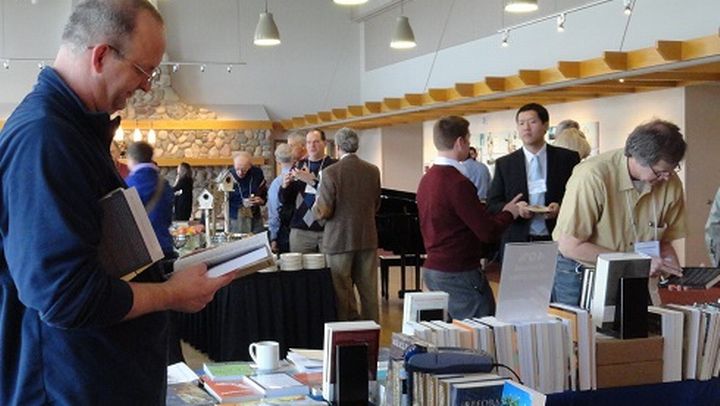

The Henry Institute’s Symposium on Religion and Public Life brought together scholars, students and practitioners from a range of disciplines to grapple with questions about religion and public life last weekend, April 27-29, for the ninth biennial symposium.

Political science professor Kevin den Dulk, director of the Henry Institute, called the institute “a research and civic engagement center at Calvin that pursues serious scholarship and civil engagement.” The non-partisan organization is united by its commitment to the Reformed tradition and its interest in working in politics as part of creation.

“We can think about politics as this dirty aspect of human experience, or we can recognize it as one area where God calls us to service, service for good,” said den Dulk. “What the Henry Institute really does — and this is the legacy of its namesake, too — is to say that to do politics well mean[s] that we need to be serious about the life of the mind, we need to think deeply about everything from how human institutions are designed, to how humans behave and what their attitudes are.”

At a panel called Religion and Political Attitudes in the United States on Thursday afternoon, presenters from four universities discussed on the intersection between social groups, religion and political views.

At the panel, Kimberly Conger of the University of the Cincinnati, presented research on the religious left, asking, “Where does conservative ideology stop and Christian theology begin? And therefore, where do religious considerations about politics stop, and liberal ideas of how politics work begin?” Conger found that the religious left was not particularly effective in bringing religious people to the polls.

However, she also found that “the Christian right shows the exact same kind of indirect impact, and shows no evidence of specific impact on evangelical political activity.” Despite the similar impact of the Christian right and religious left, Conger found that “an explicitly religious appeal may not have same effect, even for religious people who are liberals.”

Tom Copeland of Biola University gave a presentation called “American Protestants and the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions Movement (BDS).” He described a growing movement against anti-Zionists, despite mainline Christian’s initial support of Zionism.

“With the advent of the social justice approach to understanding the Palestinian conflict and the continued decline of the mainline churches, anti-Zionism is poised to shape Christian millennials and perhaps even the broader future of evangelical support of Christian Zionism in the U.S. foreign policy with Israel,” said Copeland. He concluded that Christian Zionism and anti-Zionism are part of a complicated puzzle and are worth further study.

The last panelists, professor Mark Mulder and senior Erica Buursma of Calvin College, presented their ethnographic study of Protestant Latinos’ political views. They said Protestant Latinos are a growing wing of Christianity that is doubly-marginalized due to their status as both racial and ethnic minorities.

“We see them influencing the social, economic and political climate” of the places they live in, said Mulder. “Their religion matters. We compare Latino Protestants to white Protestants, and their levels of religiosity are higher. […] The salience of their religion matters.” Their research indicated that Latino Protestant churches are very diverse, both in terms of style and in terms of political values.

The Center for Public Justice presented their annual Kuyper Lecture as part of the symposium on Thursday night, April 27.

In a lecture entitled “Rediscovering Sphere Sovereignty in an Age of Trump,” Charles Glenn of Boston University argued for school choice using some of Abraham Kuyper’s statements about “principled pluralism” and the role of government in education.

“I belong politically to the radical middle,” Glenn said, distancing himself from both liberal opposition to school choice as well as conservative efforts to cut funding from public schools.

Glenn distinguished between instruction, which is about learning content, and education, which involves character formation. According to Glenn, the government should hold schools accountable for instruction, but schools should be responsible to parents and families for education.

After Glenn’s lecture, he was joined on stage by Matthew Kaemingk of Fuller Northwest Seminary and Ted Williams of Chicago State University for further discussion about school choice.

At the end of the discussion, one audience member interrupted to ask the panel’s opinions on current U.S. secretary of education and Calvin alumna Betsy DeVos. The participants were reluctant to speak on DeVos, though Williams did call her “dangerous.”

The “Faith and the Democratic Party” panel Friday afternoon encouraged deep political thought. This panel brought together two Democratic leaders with different perspectives on the state and trajectory of the Democratic Party, Burns Strider of the Eleison Group and Michael Wear of the American Values Network. Moderated by Sarah Pulliam Bailey of The Washington Post, this discussion focused on the Democratic Party’s failure to reach out to white evangelicals during the previous election.

Wear emphasised that Clinton’s silence toward evangelical Christians negatively impacted the outcome of the election, blaming inactivity and failure to take Trump seriously as key reasons for the Democratic Party’s loss.

Burns defended Clinton, saying “Hillary probably thought there was a more robust faith operation going on than maybe there was.” Burns also called on the Democratic Party to open its doors to a more diverse constituency: “We stand to lose votes if we don’t welcome other parts of the country.”

The Paul B. Henry lecture on Friday night featured Republican senator Ben Sasse of Nebraska.

Sasse began with what would be a recurring topic throughout the night — the role of politics in our time. According to Sasse, politics are important, but they are not “everything and never should be.”

Sasse said he ran for office because he “wanted to take a seat in the Senate to block out someone else who thought politics was ultimate.”

In his recently released book “The Vanishing American Adult,” Sasse acknowledges the shift of American society from close-knit villages to distanced urban squares. With this shift comes comes instability, loneliness and “the hollowing out of work, community and friendship foundations.”

Sasse believes the loss of these foundations is truly detrimental to society — in fact, he said it is these foundations that give us “American exceptionalism.” The loss of these foundations is destructive to civil society, he said, but it is not irreversible:

“You should be volunteering, you should be coaching little league, you should be entering the neighborhoods just a few miles from you,” he said in response to a question about disagreement in politics and society. “This is about actually talking to the members of your community.”

According to den Dulk, the Henry Institute’s work is relevant to today’s political climate: “If you think about that mission statement at this moment in time, not just in the United States but globally, I can think of no more important time to be asking, ‘How does political life raise questions about key ideas, and in particular, questions about how we seek a just society through political institutions and ideas?’ And that’s what we do.”

Contributions by Renee Maring and Josh Parks.