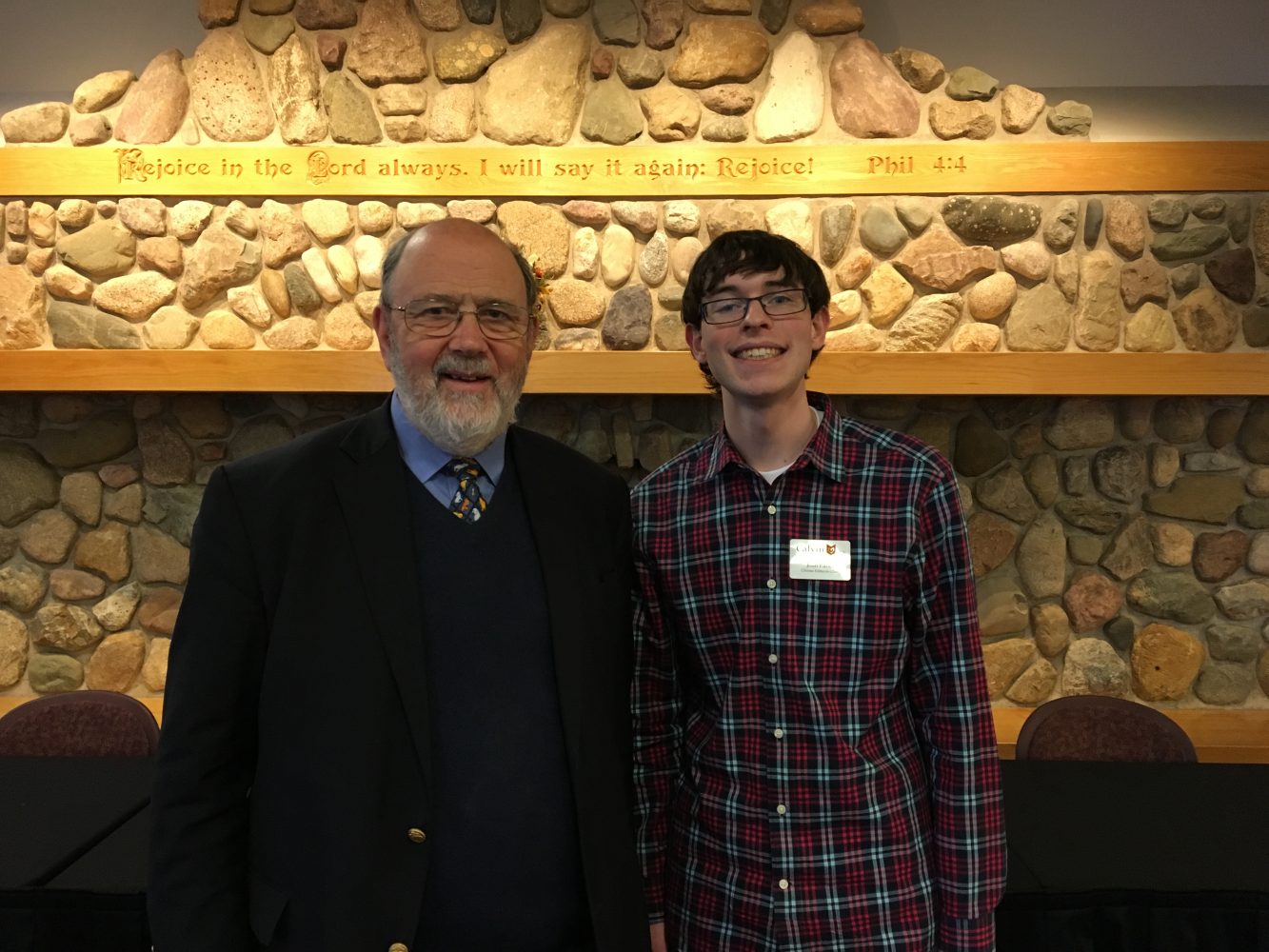

N.T. Wright is a world-renowned New Testament scholar. Before his current job teaching at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, he served as Bishop of Durham in the Anglican church. Our editor-in-chief sat down him for a brief conversation while he was on campus for the worship symposium.

Chimes: Who is your favorite Bible character?

Wright: Goodness, I don’t think I’ve ever been asked that question before. I kind of live with Paul, and I’ve lived with Paul all my adult life. I’ve just written a biography of Paul. Is he my favorite character? In a way he is, but for various reasons I find myself wanting to say Joshua.

There’s something about the command to be strong and very courageous and facing a total new challenge without a roadmap and having to trust and having to go for it, and perhaps making mistakes and all the rest of it. There’s something kind of refreshing about “Okay we’ve come all this way, now what are we going to do?” Probably I’ll wake up tomorrow and think of somebody else, but that’ll do for the moment.

Chimes: At Calvin we’ve spent a semester studying the book of Revelation. Could you say a little bit about the importance of reading and studying Revelation when it tends to be either ignored or misinterpreted?

Wright: A book like that is bound to be misinterpreted because it is so rooted in one particular way of thinking and writing — namely the world of Second Temple Judaism as reconceived through the Christian gospel — that people who really don’t know very much about that world are bound to take some of the symbols as literal prophecies. It’s been a happy hunting ground for people doing that.

However, I think without Revelation, you would lose so much. Revelation gives you the sense of an ending. I don’t think John of Patmos said to himself, “Right, we need to close this canon. I need to write a book that will finish it off.” But Revelation 21 and 22 are a brilliant, amazing, previously unimaginable conclusion to a story that begins with Genesis 1 and 2, and John certainly knows that he’s bringing those into land. There is a sense that without that, the ending is open.

And of course, people misread Revelation as though it’s simply about heaven and what heaven looks like when we get there. But the Bible is vulnerable to that, just as Jesus was vulnerable to people throwing stones in the streets. The Bible is vulnerable to being misunderstood, and that is part of the point. In order to be wise Christians, we have to do wise business with the text. It actually takes thought and care and patience and humility. Particularly, without Revelation, you wouldn’t have this lurid, high-tech sense of an alternative world in which Jesus is Lord, as opposed to the world in which different powers and systems are lords. What we might call the political vision of Revelation remains enormous important.

Because of the way the imagery works, Revelation demands that you think at different levels, that you think about the present reality of the messy world we live in and the struggles going on in God’s space and the way those two integrate with one another. Our culture does not normally think like that. We normally see things as either spiritual or material, and Revelation insists through its imagery that, sorry, these belong together.

Chimes: Which book of yours would you recommend for someone to read first?

Wright: The two which people will often say are “Simply Christian” and “Surprised By Hope.” “Surprised By Hope” is longer, but I get more letters and emails about it than all my other books put together. It’s clearly put its finger on something. So much of American culture is particularly focused, almost fixated, on heaven and hell. The New Testament doesn’t look at it like that. Hell is important, heaven is important, but this is not what the story is about. It’s about the kingdom of God coming on earth as in heaven.

I think “Simply Christian” is about as simple as I can make it. That was a difficult book to write because it was a matter of boiling down some very big and complicated ideas and trying to say them in a way which would hook people in.

Chimes: You’ve often been called a successor to C.S. Lewis. What is your favorite C.S. Lewis book?

Wright: I have a double shelf at home of Lewis, and quite often if it’s late at night and I just want something to read to relax, I’ll just say “let’s have a bit of Lewis,” because any paragraph of Lewis is worth reading — simply as a writer of English literature, an absolute master of English prose.

I’ll toss out three or four [favorites]. “That Hideous Strength,” which is the third of the three planetary novels, I think is absolutely brilliant. Very funny, but extremely clever, and partly because it contains some of the best portraits of what a dysfunctional Oxford governing body is like. And I’ve sat on dysfunctional Oxford governing bodies, and he’s nailed it.

I love his Oxford History of English Literature volume “Poetry and Prose in the Sixteenth Century.” It’s a superb book. I first came across it when I was working on the early English Reformers, Tyndale and Frith, and he has some paragraphs on them. [Lewis] had read everything. He spent ages in the Bodleian Library, and he had a photographic memory. His description of Richard Hooker includes several sentences written Hooker’s style. It could just be a boring catalogue, but it’s anything but.

I also like “The Discarded Image,” which is his account of how medieval and Renaissance literature works for post-Enlightenment people who just don’t think like that. That’s a reminder which I cherish, and I often tell students to read it when they’re studying the Bible, because the whole point is that we need to think our way back into that world so we can understand the literature of it. Otherwise you will just make wrong assumptions.

Then I suppose I have to say one of the Narnia books. Probably “The Magician’s Nephew.” For some reason I just think it has a certain depth. It’s about creation and all the stars singing for Joy, and there are some very fine passages in there. But I could go on. That’s enough for now.

Chimes: Do you have any advice for college students who struggle with doubting their faith?

Wright: The first and most obvious thing is find at least one good friend and at least one wise pastor with whom you can talk about it. Doubt is caused by many different things, and it may well have nothing to do with intellectual reasoning, though it may present itself like that. It may have a lot to do with events in your life, good or bad, with your upbringing at home or something that once happened in church.

The main thing is — and people get shocked when I say this — to doubt is not to sin. It looks to me reading the stories of Jesus in Gethsemane as though Jesus was seriously questioning whether he had misunderstood his whole vocation to go to the cross: “If possible let this cup pass for me.” That looks like a kind of gritty doubt, which isn’t opposed to faith.

Faith in the New Testament is from one point of view of the opposite of doubt: “Do not doubt but believe.” But faith is also the opposite of sight. Pauls says, “We walk by faith, not by sight.” Some people have been taught a form of Christianity which is almost a form of sight: “We just know this, and then we go out and do it.” Then when they find out the world is much more mysterious than that, they perceive what they are feeling as doubt when it may simply be a chastened faith. This is why one needs friends and pastors, because it’s a more complicated than one imagines.

Particularly within a student culture, which is very much a thinky, book, talky culture, doubt can present itself as “I have thought these things through, and I can’t quite believe this.” And I want to take those questions very seriously. But the answer ultimately — boringly, because this is a Sunday school answer — is Jesus. Jesus was and is a real person. Jesus really did die on the cross, he really did rise from the dead, and if one finds that difficult believe, fine, we can work on that.

The evidence is not rationalistically conclusive, but it converges, and as it does so, it puts someone into the position in which they can say, “I see. There is a God who does this thing called Life and is in charge of Life.” And you have to believe that, because otherwise the resurrection of Jesus would just be a quirk, like “One day there was a horse born with three heads.” The resurrection of Jesus is not just a very odd event within the old creation — it is primarily a paradigmatic event in the new creation. To believe, you have to believe that the new creation has been launched. And that is self-involving, because if new creation has been launched, I cannot be a spectator.

This interview has been condensed and edited.