You are only 10 percent human. The average human being has over 100 trillion microbes in and on their body — more than 10 times the number of human cells. These tiny travelers are not just passing through us to steal nutrients. Rather, gut bacteria perform such a range of essential functions for our bodies that many scientists are beginning to treat the gut microbiome as an organ in itself. Our microscopic friends are busy breaking down food we can’t digest, synthesizing important vitamins and folic acid, as well as protecting us from bad germs. This partnership formed while you were still young; by approximately one year of age, each person has developed a unique core microbiome that stays with him or her for life. The composition of gut bacteria species is so specific for each person that it can be used for identification, much like a fingerprint. Every time you exit a room, you leave behind a distinct pattern of microbes that can be traced back to you.

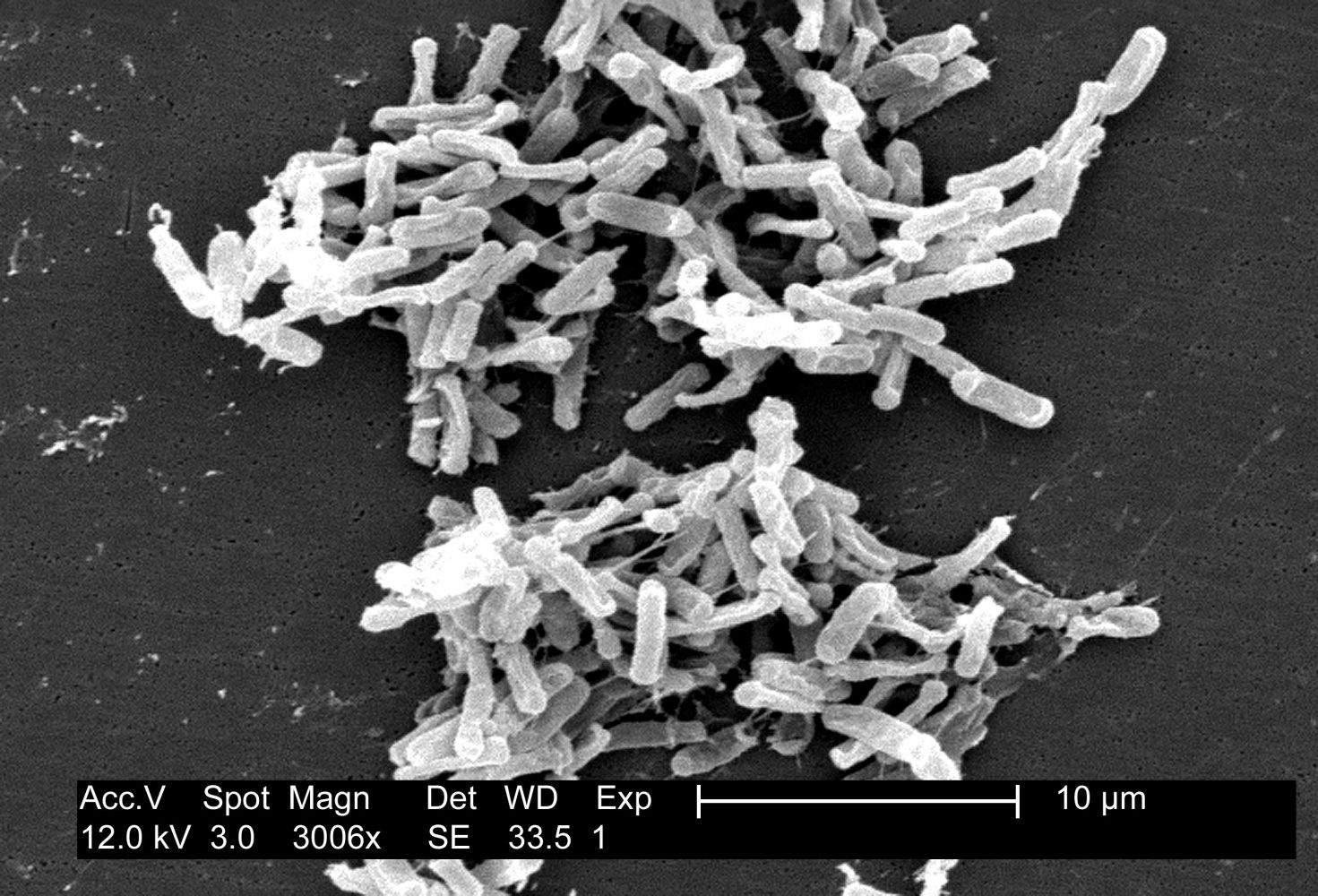

Although the gut microbiome as a whole works to keep you healthy, there may be nefarious organisms residing among the trillions of helpful bacteria. Dysbiotic diseases arise when healthy species are eliminated, leading to an overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria. One such opportunistic pathogen is antibiotic-resistant Clostridium difficile (C. diff), which can lie in wait for something to disrupt protective gut microbiota and spring into action once the competition is gone. Dysbiotic diseases like C. diff infections can arise after prolonged antibiotic treatment that erodes the healthy microbial ecosystem in the gut. Even though antibiotics are intended to attack enemy bacteria which make you sick, collateral damage is done because the drugs cannot distinguish between disease-causing bacteria and native microbes, resulting in the loss of many benevolent bacteria. With the healthy microflora depleted by antibiotics, C.diff starts producing nasty toxins that lyse and kill cells in the gut-lining. Every year, at least 14,000 Americans are killed by C.diff infection.

The challenge with treating dysbiotic diseases is that antibiotics can exacerbate the problem by killing off more native bacteria and making the imbalance worse. Though antibiotics are used to treat C. diff, treatment failure and recurrence rates are still high, and can lead to vicious cycles of treatment with antibiotics followed by recurrence due to that very antibiotic treatment. A better way to address the issue would be to allow gut microflora to recover, fight C. diff and reestablish the normal balance. This realization helped scientists come up with a new way to reinfuse a patient with their own healthy microbes via fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) — a dose of your own stool. In an ideal situation, patients with dysbiotic diseases would be infused with a healthy version of their own microbiome, a fecal sample which was frozen and stored before they got sick.

Hospitals are beginning to collect patient stool in banks as a preventative measure. However, the most common current use of FMTs are inoculation from another person, preferably a close relative. FMT is now a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved method to eradicate C. diff infection by restoring gut microflora, a process fondly referred to by microbiologists as Project ‘rePOOPulation’. A non-profit organization called OpenBiome has opened the first stool bank in the nation, collecting and distributing healthy fecal samples to those suffering with C. diff.

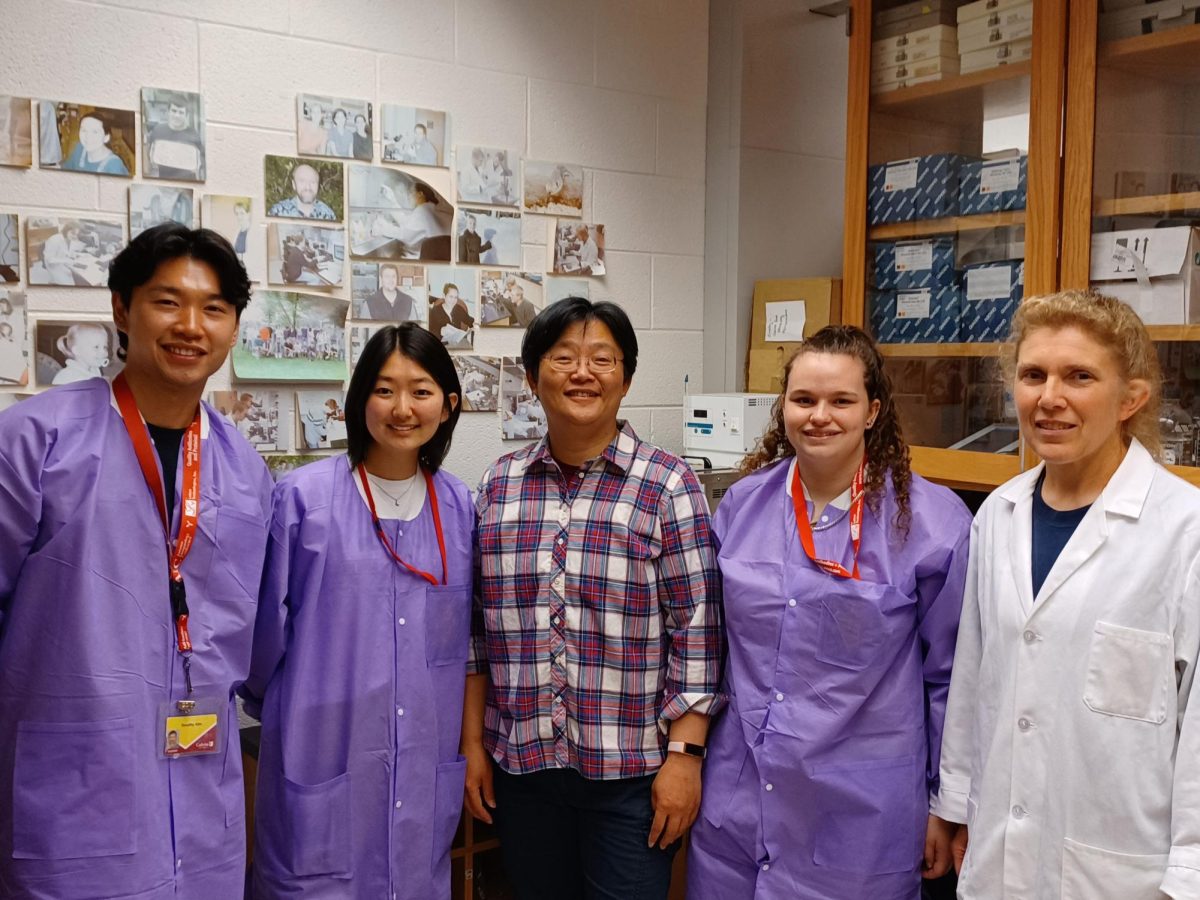

“I think giving your poop to a poop bank is a great way to make money and help people.” said professor John Wertz of the Calvin College biology department. The stool is packaged as tiny droplets of bacteria emulsified in aqueous fat and encapsulated in ordinary-looking pills in an attempt to make them not too hard to swallow.

Last month, clinicians in Europe presented data showing a 94 percent cure rate in patients with C. diff who were treated with the capsule. Despite its proven efficacy, some students have mixed feelings about the procedure. Ana Van Lonkhuyzen, a senior education major says, “It certainly is out of the ordinary, but if I am ever in a situation where I need to get treatment for something like this, I would love to have that option. That’s what I love about modern medicine — it’s so out of the box!”