Governor Rick Snyder has officially announced plans for the city of Flint and Genessee County to reconnect to Detroit’s water system in response to the ongoing Flint water crisis. On October 1, Genessee County declared a public health emergency after a study released the previous week by the Hurley Medical Center showed significantly higher blood lead levels in Flint infants and children since the switch to Flint River water.

Previous studies, compounded by these alarming medical results, affirm elevated lead levels in what experts estimate to be a 45,000 home range since the switch from Detroit’s water to the Flint River. The city’s water had actually tested positive for lead as early as September 2 but was not formally recognized as surpassing dangerous levels until October 1. The governor’s $16 million plan will help Flint with state funds to reduce the current lead levels in the city’s drinking water — $4 million was set aside to address immediate lead issues, including further testing of children’s levels.

How did this contaminated water come about? A series of complicated deals took Flint by the horns. For the past 50 years, Flint has been receiving its water supply from the Detroit Water and Sewage system. However, a new player entered the water market in early 2013, when Karegnondi Water Authority announced its new pipeline project to deliver water from Lake Huron.

After a heated duel of words between Detroit water officials and Flint officials, Flint received the blessing of the state treasurer to engage in talks with Karegnondi, which was estimated to save the city $19 million over the next eight years. Much to the chagrin of Detroit’s Water and Sewage Department (DWSD), a deal was signed on April 13, 2013.

In response, the DWSD notified the city and county that by the next year, it would stop selling Flint its water. This is where the first major problem emerged: the Lake Huron pipeline would not be finished for another three years, so where would Flint get its water from?

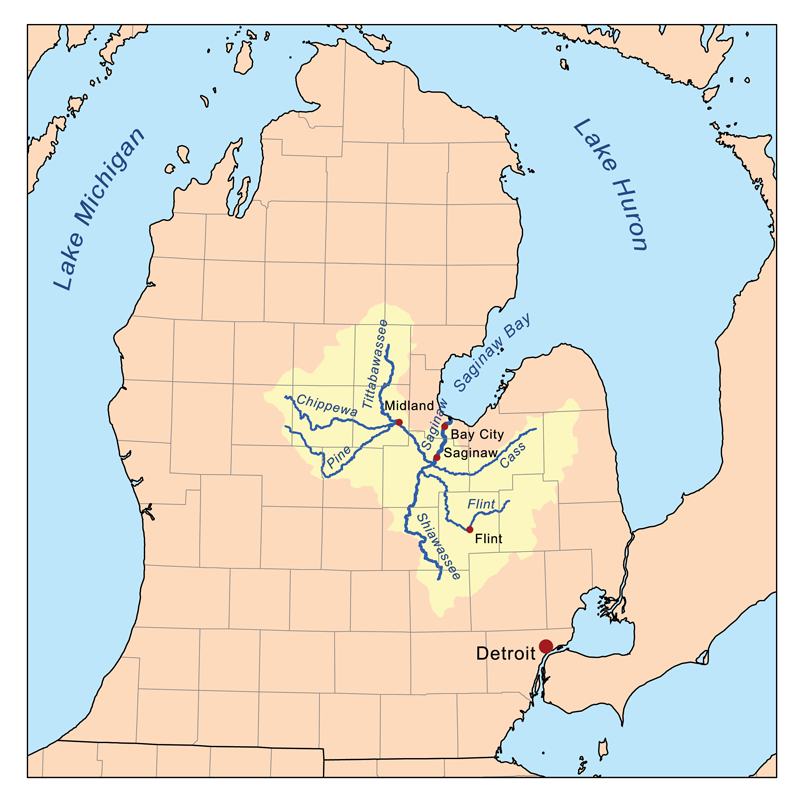

A solution sprouted and spread among the officials — water could be drawn from Flint’s own river. The Flint River cuts through the heart of the city, connecting CS Motts Lake all the way over to the Shiawassee river. Flint’s mayor, Dayne Walling, announced at the April 2014 switch, “It’s a historic moment for the city of Flint to return to its roots and use our own river as our drinking water supply.”

The council originally intended the river water to be treated at the recently renovated water plant and distributed to its city inhabitants. However, the distribution pipes throughout the city, many built before 1986, caused a series of major unforeseen problems with the once-promising plan.

First, there were the initial complaints of poor taste and smell; then came the summer’s contamination from fecal coliform bacteria. At the mark of the 2015 new year, traces of TTHM, or trihalomethanes, were detected. TTHM are byproducts of disinfectants that are harmful if consumed regularly over a long period of time (on the scale of decades).

After this third blow, Detroit offered Flint emergency water multiple times, free of reconnection charges and no lock-ins to contracts. They were frequently declined by Flint’s emergency manager. Instead, a water consultant was hired.

In mid-February, water expert Bob Bowcock and local activists called for Flint to return to its Detroit water supply. On March 23, the city council agreed almost unanimously to do so, despite the mayor and emergency manager not being present at the vote. Emergency manager Jerry Ambrose did not understand why the “city council would want to send more than $12 million a year to the system. … Water from Detroit is no safer than water from Flint.”

However, Virginia Tech professor Marc Edwards soon proved otherwise in his September 2 findings that the “corrosiveness of the water is causing lead to leach into residents’ water.” The old pipes that distributed water to Flint homes were leaching lead far more than before the switch to the Flint River supply.

Thus, the story comes full circle. After almost one-and-a-half years, Flint residents, after a frustrating and painful ordeal, are promised state help in reconnecting to a more stable water supply — the very same supplier from before this crisis. Until the water is safe, multiple organizations and local companies like GM have been donating water filters for residents.