Whenever a young person commits suicide, our understanding of the universe dies a little. It is especially so in the case of a singularly bright and determined individual, as Aaron Swartz was. For many of us, it is incredibly difficult to imagine taking our own lives and we project this difficulty onto the lives of others. It is especially unimaginable when the subject had achieved so much and held such strong convictions. In these cases, it comes naturally to swiftly assign blame and suspect malicious conspiracy. Many citizens of the internet assigned such blame to the federal prosecutors in the Aaron Swartz case, who allegedly overstepped the bounds of the law in order to aggressively prosecute a hacker whose “victim” wasn’t pressing charges.

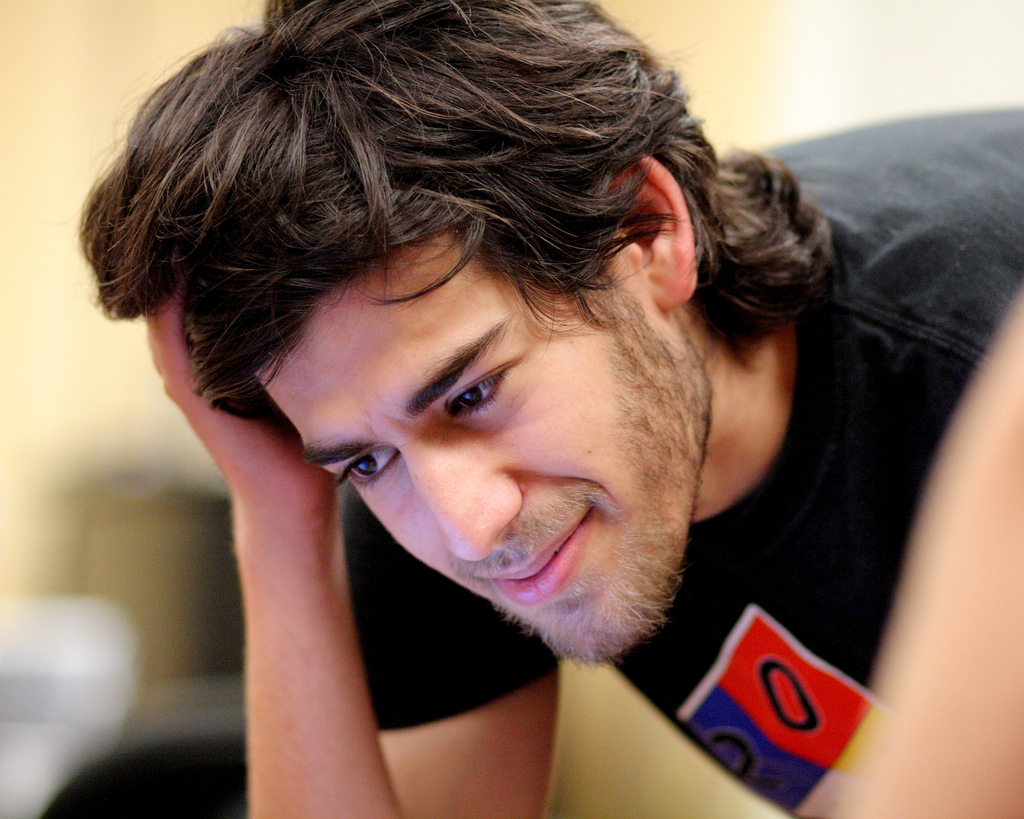

In a blog post titled “Prosecutor as bully,” Lawrence Lessig, a friend and fellow political activist of Aaron’s, points out the tragic absurdity of the case. Lessig, who met a prodigal, barely teen-aged Swartz, eulogized him thusly: “He was brilliant, and funny. A kid genius. A soul, a conscience, the source of a question I have asked myself a million times: What would Aaron think? That person is gone today, driven to the edge by what a decent society would only call bullying. I get wrong. But I also get proportionality. And if you don’t get both, you don’t deserve to have the power of the United States government behind you.”

Aaron’s family stated: “Aaron’s death is not simply a personal tragedy. It is the product of a criminal justice system rife with intimidation and prosecutorial overreach. Decisions made by officials in the Massachusetts U.S. Attorney’s office and at MIT contributed to his death. The U.S. Attorney’s office pursued an exceptionally harsh array of charges, carrying potentially over 30 years in prison, to punish an alleged crime that had no victims. Meanwhile, unlike JSTOR, MIT refused to stand up for Aaron and its own community’s most cherished principles. Today, we grieve for the extraordinary and irreplaceable man that we have lost.”

Who was this “extraordinary and irreplaceable man”? Swartz co-authored the RSS specification at 14 years old. He was an early addition to the Reddit team and stayed on until Condè Nast bought the social news aggregator. John Gruber credits Swartz with giving him invaluable advice during the creation of the Markdown syntax for converting plain text to HTML (which I am using to write this article). Technically talented, he was also a fervent political activist. At age 15 he was working with Lessig on the Creative Commons team. He later founded DemandProgress.org, a grassroots lobbying group which helped lead the anti-SOPA movement. He was a crusader against internet censorship and for information freedom.

“Information is power. But like all power, there are those who want to keep it for themselves. The world’s entire scientific and cultural heritage, published over centuries in books and journals, is increasingly being digitized and locked up by a handful of private corporations. Want to read the papers featuring the most famous results of the sciences? You’ll need to send enormous amounts to publishers like Reed Elsevier. … With enough of us, around the world, we’ll not just send a strong message opposing the privatization of knowledge — we’ll make it a thing of the past. Will you join us?” Swartz wrote this in July of 2008 in his “Guerrilla Open Access Manifesto.”

Later that year, Swartz downloaded about 18 million documents from PACER, a database of American court documents. Aaron, among others, felt that it was unjust for the database to charge a fee in order access information in the public domain. He downloaded approximately 20 percent of the database during a free trial at the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals library and released the information. This resulted in an FBI investigation, but no charges.

In September 2010, Swartz bought a laptop and downloaded JSTOR articles on MIT’s campus. MIT has an open campus and offers guests 14 days of free access to the network per year. Swartz used a temporary email address to register with MIT’s network and a web-scraping python script to download articles from JSTOR. In doing so, he violated JSTOR’s terms of service, which state: “you agree that you will not: … undertake any activity such as computer programs that automatically download or export Content, commonly known as web robots, spiders, crawlers, wanderers or accelerators that may interfere with, disrupt or otherwise burden the JSTOR server(s) or any third-party server(s) being used or accessed in connection with JSTOR; “ When JSTOR blocked his IP address, and eventually his MAC address as well, Swartz changed them, eventually wiring his computer directly into the network from a closet.

On January 6, 2011, Swartz, with a bicycle helmet obscuring his face and suggesting his awareness of a security camera, removed computer equipment from the closet. The MIT police arrested him later that day. In all, Swartz downloaded over 4 million articles. JSTOR settled the matter with Swartz and did not press charges. In September of 2011, JSTOR made its public domain content freely accessible. The U.S. government, however, moved forward with the prosecution, charging Swartz with four felonies, which later ballooned to 13. On January 11, 2013, Swartz was found dead in his apartment. He was 26.

Experts on the law have taken opposing opinions on the fairness of the charges against Swartz and the proposed punishments. Lessig argues that the prosecutors acted overzealously towards a victimless, but nonetheless morally wrong, crime. Orin Kerr, on the other hand, argues that many of the charges were legitimate and that “some punishment was appropriate,” but adding that some of the laws in question are in need of limitation or revision.

Kerr deduces that, while the maximum sentence was 35 years, Swartz “was facing anything from probation to a few years in jail if he went to trial — depending largely on how you value the loss he caused — and either a 4 months in jail or 0-6 months in jail if he pled guilty.” Kerr connects finger-pointing at the DOJ’s aggressive tactics with “a natural instinct to restore a sense of order to the world by finding someone to blame.”

Swartz left no suicide note, thus we will never know what his motivations for hanging himself were. Whether from the stress of the trial or his history of depression or something else, a 26-year-old is dead.

“Aaron dead. World wanderers, we have lost a wise elder. Hackers for right, we are one down. Parents all, we have lost a child. Let us weep.” – Tim Berners Lee