The Downsize Pt. II: ‘We’re committed to uncertainty’

November 13, 2021

For most of the summer of 2020, Will Miller was nervously counting down the days until he’d be laid off.

The young biology professor had known since May that it was a possibility. Many of Calvin’s academic departments were sharing in the budget cuts and program eliminations necessary to weather the pandemic, and rumor had it, the biology department would need to lay off a faculty member to do its part.

As the newest member of the department, Miller would likely be the one to go.

Finally, in late June, the call came. Miller was informed that he would be let go when his contract was up at the end of the summer.

“That was a hard place to be,” he told Chimes.

Miller paused. “My wife and I moved here for Calvin and we really were starting to settle in and engage the community, so it caught us so off guard, even though we knew this was a larger trend that was happening.”

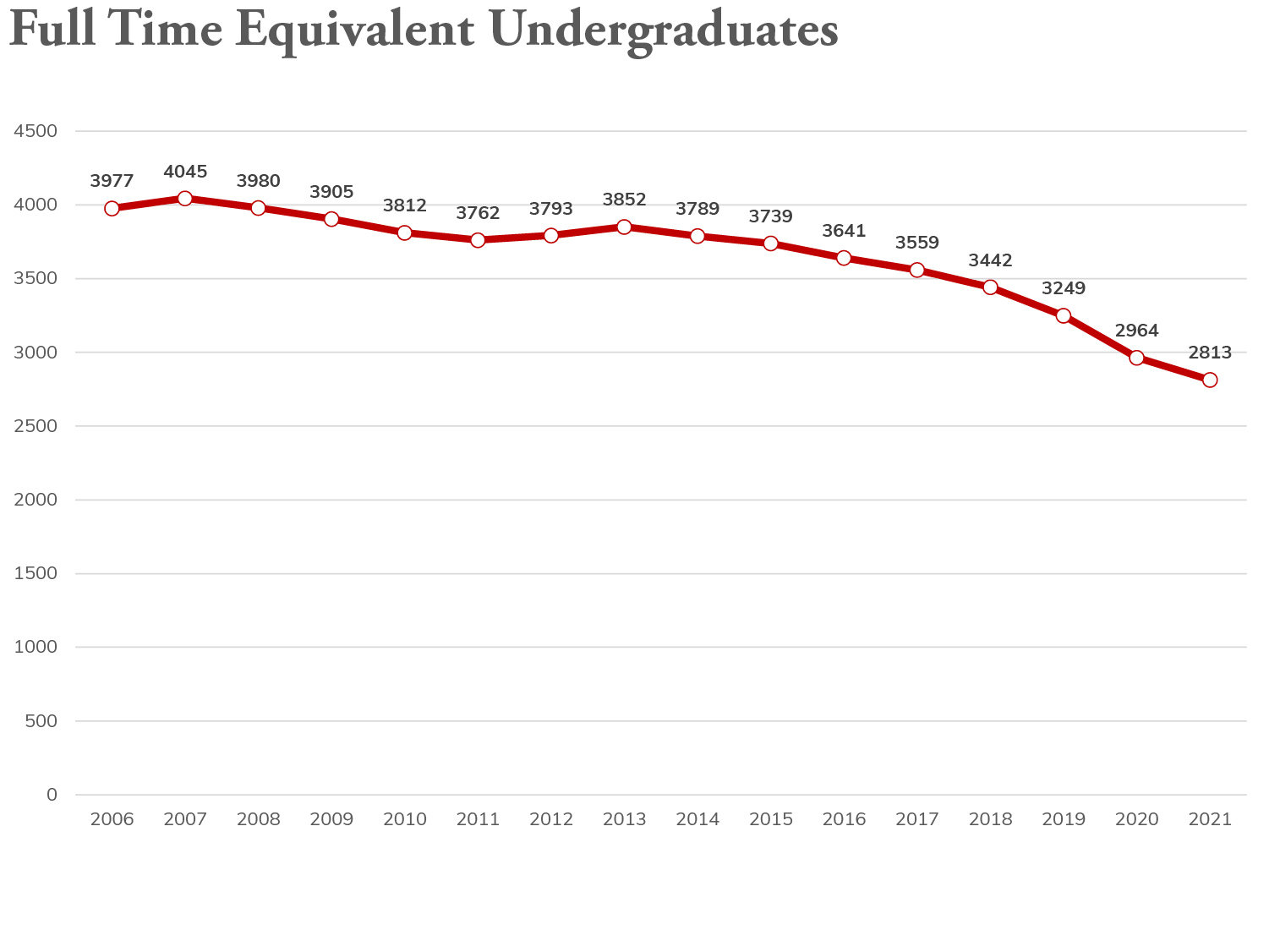

Miller, and the 12 other faculty members who were laid off in the summer of 2020, experienced the consequences of long-foretold financial and enrollment declines in higher education — issues that the COVID-19 pandemic only accelerated.

Behind closed doors, faculty are growing tired. And many are frustrated with the way top administrators have made these painful, yet necessary, cuts to personnel and programs over the past few years — often with the livelihoods of faculty and staff hanging in the balance.

As discussions over how to better do program review play out in the upper levels of the university, hundreds of Calvin employees are doing their best to go about business as usual, knowing that more layoffs could lie just ahead.

Unlike the 12 other faculty members who were notified that they’d be laid off in 2020, Miller’s Calvin career took a positive turn. In July, when another member of the biology department voluntarily resigned, Miller was offered the chance to continue in his position as an associate professor. Today, he still works at Calvin, but feels far from secure in his position.

‘An odd dichotomy’

Miller is the stereotypical image of a biology professor. His baseball cap, flannel shirt and blue Marmot jacket look just as much at home in the halls of the science building as they would doing research in Calvin’s ecosystem preserve.

The months from April to August are Miller’s favorite part of working at Calvin. Since he came to the university in 2018, he’s worked with more than half-a-dozen summer research students as a mentor and guide.

Even amid the stress he felt during the summer of 2020, he enjoyed his work. Miller and three student researchers had just kicked off a multi-year study of tick ecology and disease transmission.

His commitment to students and his peers doesn’t end with the work day. Miller lives just a short walk off campus, behind the nature preserve and Gainey Fields — an intentional choice, he says, to engage more with the Calvin community.

He’s still doing just that.

When he was offered the chance to continue at Calvin in July 2020, Miller faced a tough decision. After everything he’d been through, it was his personal beliefs and the connections he’d built to the Calvin community that persuaded him and his wife to stay.

“We still felt God calling us to be here, to be engaged and active in this place. So, that decision was hard and easy at the same time,” Miller said.

Almost two years later, Miller harbors no resentment toward the university — he’s clear about that. But the hurt remains.

“It’s an odd dichotomy. It’s possible to both understand the challenges and burdens institutions of higher ed are under right now and also to mourn and lament those processes,” he said.

Even as they tearfully announced the program losses and faculty cuts of 2020, University President Michael Le Roy and his cabinet sought to reassure the Calvin community that the university’s financial position was strong. Meanwhile, the 12 former professors who weren’t as lucky as Miller began packing their things into boxes and searching for new employment. Because of the abrupt notice, they were left searching for teaching jobs just two months before the start of the academic year. In 2021, the cycle repeated: Calvin laid off tenured professors Corey Roberts and David Noe in June after deciding to cut their respective departments, German and classics.

Still, administrators pushed a message of underlying institutional stability.

“Our financial foundation is solid, but it is only because we have made hard choices over the past few years,” wrote Le Roy in a campus-wide update on July 2, 2021.

Not all faculty were convinced. Many wondered if more “hard choices” were yet to come in the year ahead. And if so, would they be notified in time to find employment elsewhere?

On Aug. 31, the first Faculty Senate meeting of the year opened in tension, rife with questions for administrators and calls for accountability.

With the support of nine other faculty senators, physics professor Loren Haarsma brought to the floor a series of motions aimed at increasing transparency and providing earlier warnings to faculty and departments that might find themselves on the chopping block.

Some disagreed with the sentiment of the motions. The new provost, Noah Toly, had made promises that program review processes would be different going forward, and some argued he should be given the benefit of the doubt. Rather than push for change immediately, Faculty Senate should wait and see before acting.

But in the end, all four of Haarsma’s motions passed with overwhelming support.

“We’re done with ‘Trust us.’ We’ve done that,” one senator said. “This is the day that we decide whether we act in a way that will keep the university accountable.”

For Toly, who became the university’s provost just months earlier, the motions echoed the hurt, distrust and low morale he’d been observing in departments across campus.

“When we experience the kinds of things like the pandemic or declining enrollment over the last few years, there are rightly lots of people who want us to make sense of it and not just make a strategy,” Toly told Chimes in an interview in mid-October.

So, while the new provost set to work on a long-term plan for Calvin’s academic future, he also voiced a singular short-term goal: transparently return Calvin’s termination processes to academic norms.

Put more simply, “I want to get to the point where people have a runway to plan in the case that there will be a separation, and where we are giving terminal years if that separation is involuntary,” Toly said in October.

To reach his short-term goal, the provost spearheaded the Voluntary Exit Incentive Program, which offered tenured professors with more than 15 years of experience financial incentives to voluntarily resign. The program received public backlash across the university as many considered it a push for tenured professors to leave. Faculty were given a month to decide whether or not they would participate, with no idea how many exits were necessary to prevent involuntary layoffs. It was, as one professor would later call it, “a classic prisoner’s dilemma.”

But while the program drew the frustrations of many, it also drew enough participants to spare the university the pain of having to fire even more professors this year. The administration declined to provide the total number of VEIP participants. “It appears that the outcome of the Voluntary Exit Incentive Program will effectively achieve our goal of resetting the rhythm, context, and task for academic planning,” Toly wrote in an email to faculty on Nov. 5.

As of that announcement, the provost said he does not expect to see any faculty layoffs in the year ahead.

The VEIP bought Toly, and the members of the president’s cabinet, time to plan, but major challenges lie ahead for Calvin, specifically, and higher education institutions more generally.

Addressing mixed messages

At an all-faculty assembly on Oct. 18, Le Roy publicly addressed frustrations and confusion over mixed messages about the university’s financial health. How could Calvin continue to lay off professors while spreading the message of financial stability?

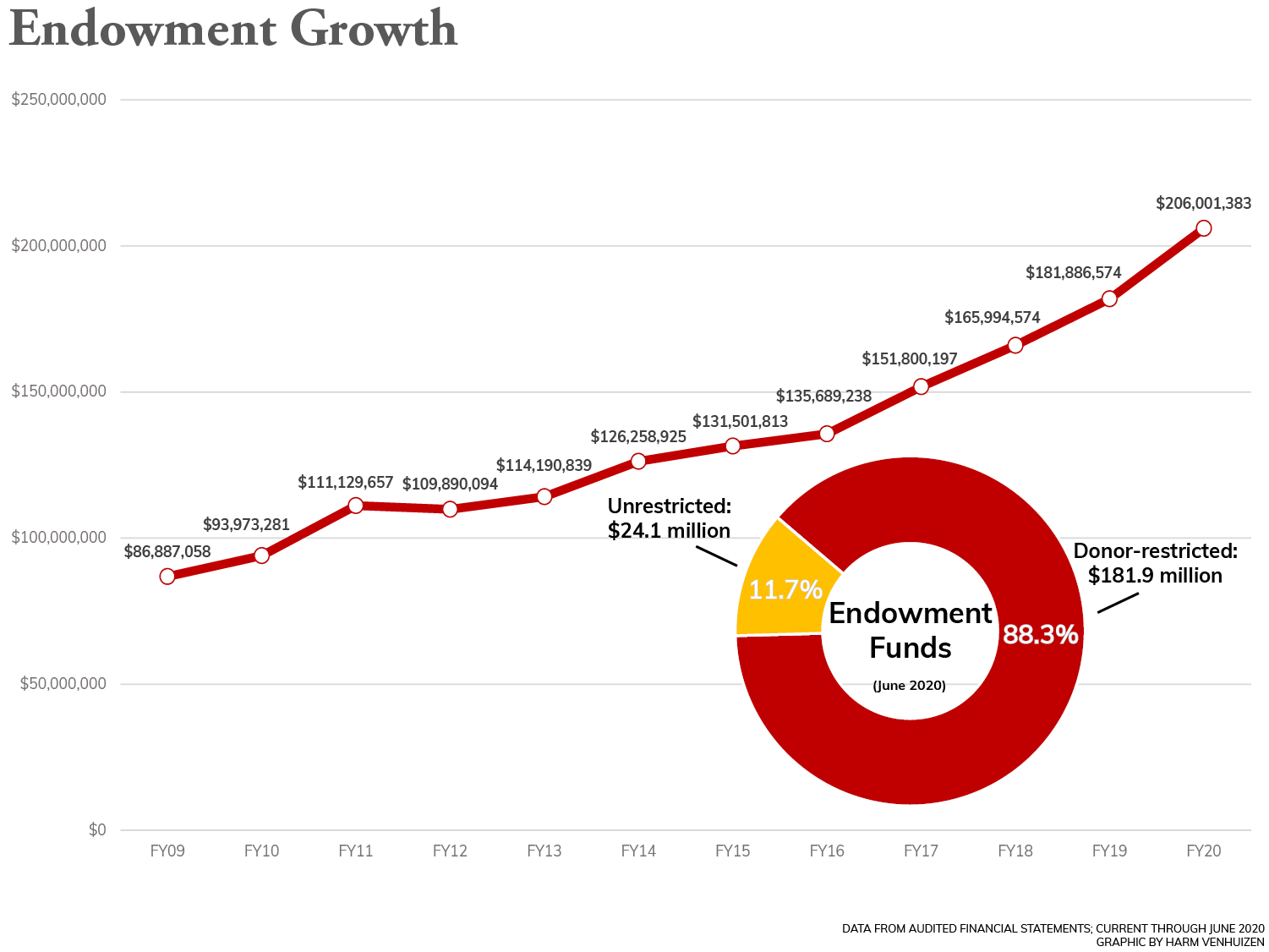

“Our financial house is in good order, but our fiscal house is distressed,” the president said in response to faculty questions. It was a simplified way of saying that, although Calvin’s endowment has been flourishing, the annual operating budget is not.

Calvin’s endowment — the funds set aside to provide for the university in perpetuity — currently totals approximately $206 million, according to tax forms from the fiscal year ending in June 2020. This means the endowment can contribute more than $6 million in revenue each year.

Much of the money in the endowment, however, is limited by donor restrictions stipulating how it can be used. For instance, scholarship and department-specific funds are included in the endowment.

When administrators speak of Calvin’s financial strength, they’re referring to the size of its endowment. When cuts are necessary, it’s because a healthy endowment is not sufficient for a healthy budget.

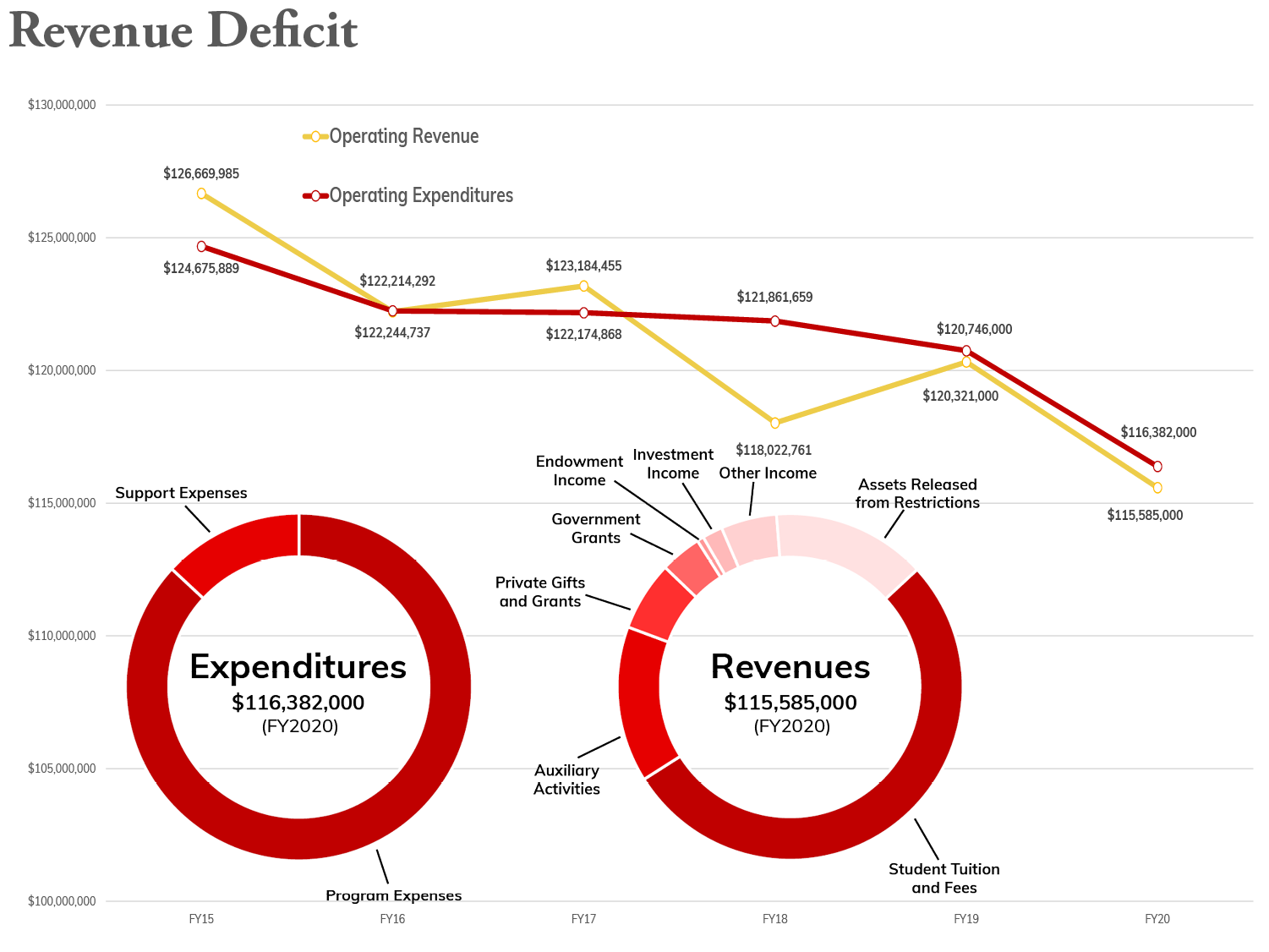

In fiscal year 2020, it took more than $116 million for Calvin to operate.

A healthy budget relies on the ability to match expenses and revenue. In recent years, institutions of higher education have broadly seen significant decreases in revenue. Program cuts and layoffs are one way Calvin has sought to bridge the gap. Strategic investments and the creation of new sources of revenue are another.

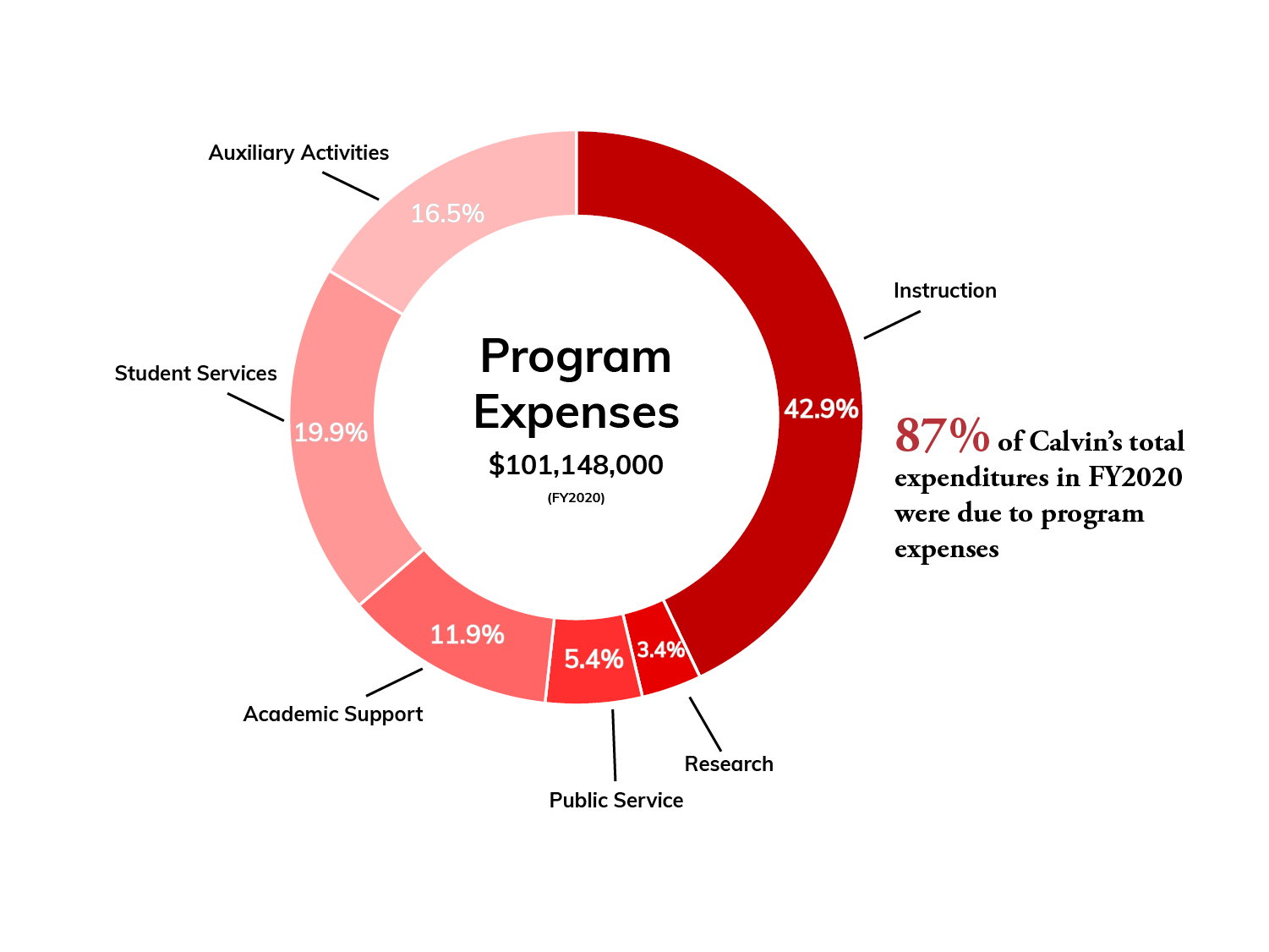

Program expenses are by far the largest portion of the university’s operating expenditures, accounting for approximately 87 percent of costs in fiscal year 2020.

Support expenses, like facilities maintenance and depreciation, made up the other 13 percent, or $15.23 million.

When it comes to revenue, student tuition is typically the largest source for institutions of higher education. In 2020, it comprised 54 percent of Calvin’s total revenue, followed by auxiliary activities at 15 percent, which included sources like room and board as well as conferences and events.

With the pandemic-related decreases universities like Calvin experienced in tuition, room and board and event revenues, cuts needed to be made.

“When we look at the past few years and see a balanced budget, what we might miss in a graph or a table or the operating budget is the effort it took to balance that budget,” Toly said. “We see in the end that it’s balanced, but the numbers don’t tell us what it took to get there. As revenues have decreased, there have been a lot of painful cuts and difficult choices about how to decrease expenses along with revenues.”

Astronomical consequences

Larry Molnar came to Calvin in 1998 to start an astronomy program. In the more than two decades that followed, he oversaw the founding of a research facility, watched Calvin students make outstanding discoveries and reached national acclaim for his research and predictions in the field.

Last year, he watched the astronomy program die.

Molnar arrived at the university shortly after the engineering department split off from the physics department.

“Physics was asking itself, ‘So, if we have fewer [engineering professors], what new thing will we do instead?’” Molnar told Chimes.

Their answer was to hire two astronomers: Molnar, who holds a doctorate from Harvard, and Deb Haarsma, an MIT graduate and the wife of Loren Haarsma, who brought forward the four Faculty Senate motions in August.

“They hired us with the mandate to start a program, so to add a few courses and to get some equipment,” Molnar said.

Soon, students were studying the stars from a rooftop observatory, astronomy courses and a research facility in New Mexico.

The astronomy minor at Calvin was never a large program — a fact that Molnar is the first to admit, but the research he and his students performed was top-notch.

In the early years of the program, after the university’s telescope facility in New Mexico was established, Calvin researchers discovered more than 180 new asteroids.

In the past three years, two astronomy students were awarded Goldwater Scholarships, one of the most prestigious STEM awards in the nation. Approximately 410 such scholarships are awarded in the U.S. annually.

Molnar’s work in the astronomy department is also the center of a recent documentary produced by film professor Sam Smartt. “Luminous” tells the story of Molnar’s bold public prediction in 2014 that a star he’d researched — actually two stars caught in each other’s gravitational pulls — would explode in the near future. It was the first prediction of its kind, and ultimately incorrect, but the research performed by Molnar and his students on KIC 9832227, as the system was named, led to national attention.

The future of astronomy at Calvin is now unclear. The astronomy minor was among the programs eliminated in June 2021, but some astronomy courses are still being taught, and Molnar says administrators have expressed interest in continuing the research being performed at Calvin’s observatory and in New Mexico.

To Molnar, the most difficult fact to wrestle with was that reviewers hadn’t performed a cost-benefit analysis before recommending that the astronomy minor be eliminated. The university even declined two offers made to fund two years’ worth of the savings created by cutting astronomy courses.

“You would presume that when you hear of these big cuts, somebody must have looked at the financials and said, ‘We need to save a certain amount of money,’ and then found cuts that would save that money,” said Molnar. “I recognize that’s an unenviable job for anyone to have, but somebody has to have it.”

‘The least painful solution’

Just a short walk away from Molnar’s office, through the winding halls of the Science Building, sits Gayle Ermer, chair of the engineering department and co-chair of the Academic Program Review committee. It was her job, along with the provost and nine other committee members, to recommend which of the university’s programs should be cut.

Their responsibility wasn’t just to consider finances.

“I think what most people don’t realize is just how complicated this is — that it isn’t as simple as saying, ‘Okay, here’s x number of dollars we need to reduce,’” Ermer told Chimes in September. “And even if you did have a number, there are a lot of different strategies you could use to get to that number.”

According to Ermer, not having a specific number in mind gave the committee the freedom to give struggling programs a chance if they thought things could turn around.

“Our job was to look at all the consequences of all those different options, and determine, honestly, the least painful solution,” she said. “When you’re faced with difficult constraints, it’s not like you can ignore them and keep everybody. Of course, that’s what we want to do. We don’t have any programs at Calvin that are bad. Every single program is valuable and has students invested in it, has faculty invested in it, and has good outcomes.”

The challenge of locating the least painful cuts to make is in part why the crucial panel tasked with evaluating programs exists in the first place, but members didn’t expect it to become their primary function.

The committee was formed in 2018 as a means of strategically planning the types of programs Calvin would offer. It was not the first time cuts had been made or programs reviewed at the university, but it was an attempt to create a more structured system to do so. Part of the APR’s duties included a major review of every department, every five years.

For each review, the committee would send one of four recommendations — invest, sustain, place on notice, or discontinue funding — to the Educational Policy Committee and the Planning and Priorities Committee.

“We started to recognize that, if you’ve got fewer students, you can’t necessarily have as many programs,” Ermer told Chimes.

When the APR began its work in the spring of 2018, the university was more than halfway through its fourth year of steadily declining undergraduate enrollment. By spring 2020, the committee had established its five-year review cycle and began making funding recommendations.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and the APR’s role in planning Calvin’s academic offerings shifted.

“That was really rough. They were projecting the budget for 2020-21, and they just said, ‘We need to reduce the headcount of regular faculty. We don’t have enough money to continue in this way,’” Ermer said.

It then became clear to Ermer that annual financial evaluations were about to become part and parcel of the APR’s work.

“This wasn’t just like a Band-Aid for one year,” Ermer said. “It was thinking strategically about making decisions in the short-term reach on a trajectory into the future.”

Committee members hit the books, reading up on how other universities carry out program review and exploring the criteria used in an earlier academic prioritization at Calvin in 2015.

Their research led them to consider five categories — the same used in 2015: quality of outputs, alignment with the university’s strategic plan, financial sustainability, external demand, and internal demand.

Although the criteria hadn’t changed, the acceptable performance levels in each area were more demanding — a reflection of the pressures faced in planning the university’s budget.

“We did almost all the work between April and June,” said Ermer. “That was painful. That was not what we wanted to do … And then we started the second cycle with the last academic year, 2020-21, knowing again that we were probably going to have to match the trajectory of the number of faculty to the number of students at the university.”

According to Ermer, almost all programs score well in the quality of their outputs and alignment with the strategic plan. That left the committee only three categories to really consider in depth.

“I think our recommendations indicated that further cuts might be up against that barrier in the future,” Ermer said. “Going forward, we are going to have to answer that question of, to what extent do those other factors (strategic alignment and quality of outputs) balance the demand and the financial constraints such that we might not cut something, even if it performed relatively low against those standards.”

For the cuts made in 2020 and 2021, the APR used modeling software that projected future enrollment numbers by program and also placed an emphasis on faculty-to-student ratios. Where there were fewer students projected, the committee assumed fewer professors would be needed. Where there were high-level courses with only a handful of students enrolled, the committee saw opportunities to free up faculty teaching hours.

Ermer is an engineer. Surrounded by the physics textbooks and stacks of legal pads strewn about her office, that much is clear. Given her background, the modeling just made sense. It enabled her team to guess and check, just like engineers doing design work. Committee members could model a cut in one area and start to see the ripple effects it might have across the university. Unlike engineering, however, the variables members of the APR were modeling represented the livelihoods of their peers.

“It feels like really thankless work. The part of me that’s an engineer and into data analysis thinks this is really interesting — the idea of evaluating and analyzing and comparing. But the effects of the work, obviously, are painful,” said Ermer.

The difficulty of the APR’s work is something even those affected by it are sympathetic towards.

“There are real and personal effects, and there are institutional effects to all these cuts, and I don’t wish those decisions on anyone,” Will Miller said.

Almost every one of the more than a dozen professors Chimes has spoken to expressed similar sentiments.

The future of program review

With the year of fiscal stability the Voluntary Exit Incentive Program has bought him, Toly plans to change the way Calvin does program review. In fact, he wants to no longer do program review at all. Instead, the provost hopes to create a process of “portfolio management.”

It’s abnormal, he says, to plan the staffing level of a program based on financial pressures and then make immediate personnel cuts, as Calvin has done in the past.

“The normal thing to do is to plan for the mix of programs that you want in your academic portfolio — the mix of offerings you want to give students — and to base personnel decisions on the programs you’ll be adding or keeping, or the programs you’ll be deleting,” the provost told Chimes in an interview on Nov. 11.

In recent weeks, Toly and members of the administration have set up the Academic Portfolio Planning Task Force. Its composition is in part a response to the motions passed by Faculty Senate in August.

The largest group of membership is comprised of faculty, but the task force will also include the provost and two administrators as voting members, an academic division staff member and a faculty senator jointly appointed by the provost and the vice-chair of Faculty Senate. A handful of administrators familiar with university data will also serve in a strictly advisory capacity.

“The APR was certainly built to grow into this in the past, but the pandemic prevented it from developing in the way that lots of members wanted it to. So, it was still very much focused on individual programs even though it wanted to move into a portfolio planning mode,” Toly said.

To move beyond year-to-year program reviews, the APP Task Force will consider two new criteria when deciding which programs Calvin should offer, or cease to offer, in the future.

First, the new task force will take into account how well programs serve the university as a whole and work in relation to one another.

Second, the task force will also consider financial data based on the number of students in each program and its classes, as well as trends in higher education to predict financial viability. In the past, the APR has used proxies like faculty-student ratios and the number of adjunct professors in a department as metrics for financial efficiency.

At the end of the day, however, decisions won’t just rely on data. Just like in the APR, members of the task force will be responsible for guiding the future of academic programs at Calvin.

“The work of portfolio planning involves judgment calls,” Toly said. “The numbers will never tell us what programs we should have and what programs we shouldn’t have, independent of our judgment. Planning for the future mix of academic programs will require wisdom and discernment, not just calculation and analytics.”

An immovable mission

Amid all the fear and changes of the past few years, two things still bring Will Miller hope: the people he works with every day and the new ideas and discussions he sees popping up around campus. Among those new ideas, new ways of looking at portfolio planning and outside-the-box solutions to the pressures Calvin faces.

“We have something special here — faculty members that care about each other and about their students and a common source of mission,” Miller said. “When the rubber hits the road, those things will still be there, and those things make us distinct. Christian identity and shared relationships — those are the things that are going to move us past where we’re at right now.”

In the month after he was laid off, Miller saw those distinct values firsthand as colleagues came over to his house and talked with him on the phone to ensure he and his wife were doing well and supported in their transition.

After receiving the opportunity to continue in his position at Calvin, he faced a tough decision: stay at the university that had let him go just a month earlier or leave and face a year of uncertainty and quite possibly unemployment.

His personal mission, and his wife’s support, were part of what drew him back to Calvin.

“I always saw it as my mission to engage vocation and Christian calling, and to help others do the same,” Miller said. “So, yeah, it was hard — it felt like whiplash — but I still believed in the mission, I believed in my family’s mission, so we believed that this was still an opportunity to go on with that.”

Two years later, that mission remains.

“The one thing that has been immovable throughout this whole process and that has held true these last two years is still our commitment to the mission, and really I mean on a family level,” he said. “It takes a lot for me to commit and to ask my wife to commit to the same thing. We’re committed to uncertainty, if that makes sense.”

It’s a commitment that every member of the university can share in, and many do. In spite of layoffs, declining enrollment and the realities of pandemic-life, hundreds of employees get up each day and clock in to their jobs, ready to contribute to their corner of campus, come what may. Like Will Miller, Calvin University is committed to uncertainty.

Clay Shirky • Nov 30, 2021 at 9:08 am

Mr. Venhuizen, I wrote about this series in a newsletter I write about higher education:

https://www.getrevue.co/profile/cshirky/issues/transformation-of-higher-ed-calvin-chimes-first-donation-collapsing-sat-894765

Randall Bytwerk • Nov 17, 2021 at 9:09 pm

This is an excellent article.